Banks contend that equity capital is expensive and that an increase in capital requirements will adversely impact bank services, including the volume and cost of mortgages and corporate loans. For example, JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon said in 2017 that “It is clear that the banks have too much capital…and more of that capital can be safely used to finance the economy.” In a recent staff report, we compare the different treatments of short-term credit commitments under the Basel I and Basel II Accords to assess the effect of capital regulation on banks’ cost of capital.

Basel Capital Requirements for Credit Commitments

The Basel I Accord, introduced in 1988, assigned a risk weight for each on-balance sheet exposure and specified the minimum amount of capital that banks had to hold against their risk-weighted assets. The Accord also specified a credit conversion factor for credit commitments. Commitments to lend to corporations with a maturity in excess of one year received a 50 percent conversion factor. In contrast, commitments with a maturity of up to one year received a 0 percent conversion factor. As a result, banks were not required to set aside capital when they extended commitments with a maturity of less than one year but had to do so when they extended commitments with a maturity in excess of one year. Subsequently, the Basel II Accord sought to reduce the “special” treatment granted to short-term credit commitments.

U.S. banks were required to begin applying Basel I rules on a transitional basis in 1991 and the Accord was fully phased in by 1993. As for Basel II, the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors approved the final rules to implement the new framework in November 2007, but the Accord had been finalized in June 2004 and U.S. agencies began accepting public comments on the Basel Committee’s consultative document in January 2001.

To the extent that capital is costly, the more favorable treatment of short-term credit commitments under Basel I likely made these facilities relatively less expensive—an advantage that was seemingly reversed with Basel II.

Effect of Basel Rule Changes on Use of Credit Facilities

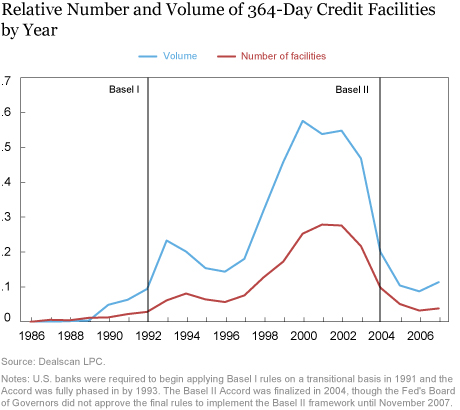

Activity in the corporate market for credit facilities around 1993 and 2004 suggests that the Basel Accords were impactful. Up until the early 1990s, there was not much evidence of 364-day facilities in the market (see chart below). These facilities were developed in response to Basel I because they run for 364 days, one day short of the duration at which banks had to reserve capital against unused portions of revolving credit lines. Soon after the implementation of Basel I, 364-day facilities became quite prevalent, only to start losing popularity once the impending change under Basel II became clear. These effects appear to be related to the Basel Accords and not to changes in the demand for credit because both the relative volume and number of 364-day facilities increased following Basel I and declined after Basel II.

Effect of Capital Regulations on the Price of Credit Commitments

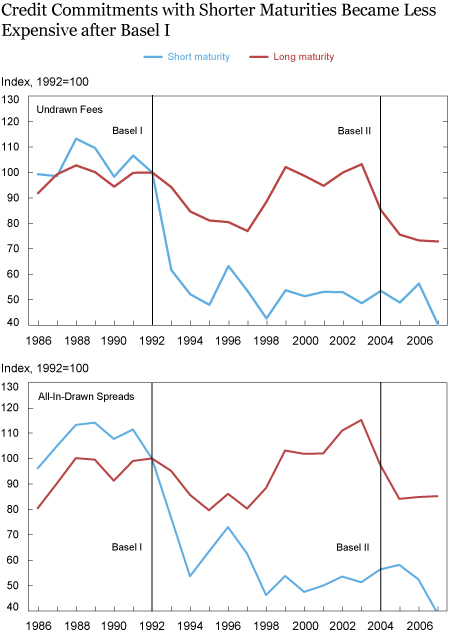

To gauge the cost of bank capital, one needs to determine the impact of the Basel Accords on the pricing of both short- and long-term credit commitments. The pricing structure of a credit commitment includes both an undrawn fee and an all-in-drawn spread over Libor. The former compensates the bank for the liquidity risk it incurs by guaranteeing the firm access to funding at its discretion over the life of the credit line. In contrast, the latter compensates the bank for the credit risk it incurs when the borrower draws down its credit line. The Basel Accords’ “special” treatment of short-term commitments applies only to the portion of the commitment that is undrawn. Given this, we would expect the Accords’ effects to be concentrated on undrawn fees. However, reducing the price of credit risk could also induce a firm to switch to a shorter maturity commitment that is unlikely to be fully drawn.

Commitments with maturities up to one year, including 364-day facilities, became relatively less expensive following the passage of Basel I (see figure below). Both the undrawn fees and all-in-drawn spreads on these commitments declined relative to those of commitments with maturities longer than one year. Commitments’ pricing around the finalization of Basel II yielded exactly the opposite results on both undrawn fees and all-in-drawn credit spreads. Importantly, these differences continue to hold when we account for a variety of factors that explain the pricing of commitments and they appear to be driven by the Basel Accords. Our research shows that undrawn fees on short-term commitments declined by 5 to 6 basis points after Basel I, or roughly 15 percent of the average undrawn fee, whereas all-in-drawn spreads declined by 15 to 25 basis points, or 5 to 7 percent of the typical spread.

Effect of Capital Regulations on Cost of Bank Capital

The price adjustments in short-term commitments following the Basel Accords are a reflection of the cost that banks are willing to pay in order to reduce capital requirements. Our findings based on the Basel I Accord suggest that banks are willing to pay at least $0.04 to reduce their regulatory capital by one dollar. While perhaps below what banks suggest is their marginal cost of capital, our estimates represent a lower bound. Nonetheless, the price reductions they offered were enough to induce a significant change in the maturity composition of credit in the marketplace.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Matthew Plosser is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Matthew Plosser is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

João A.C. Santos is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

João A.C. Santos is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Matthew Plosser and João A.C. Santos, “The Cost of Regulatory Capital,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), October 3, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/10/the-cost-of-regulatory-capital.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics