How does competition among banks affect credit growth and real economic growth? In addition, how does it affect financial stability? In this blog post, we derive insights into this important set of questions from novel data on the U.S. banking system during the nineteenth century.

The Effects of Banking Competition

According to Econ 101, an increase in competition should—under fairly general assumptions—lead to lower prices and greater output. Therefore, in the case of banking, increased competition should lower interest rates on loans and increase interest rates on deposits, resulting in more credit and deposit creation. However, banks are different than other, nonfinancial firms. For instance, banks specialize in obtaining information on the creditworthiness of their borrowers. If competition undermines banks’ incentives to collect and produce information on the creditworthiness of borrowers—because, for example, borrowers switch to other banks—competition could instead decrease the amount of credit available.

In addition, competition may create incentives for banks to take on more risk. Because the costs of bank failures are not fully borne by their shareholders but instead shared with depositors and other third parties, it is important for banks to have some “skin in the game.” However, when banks operate in highly competitive markets, they are less profitable and their “going concern” value (that is, their charter value) is lower. Hence, banks may be more willing to take on unnecessary risks in more competitive markets, since they have less to lose if things do not go as planned. On the other hand, competition may decrease the overall risk in the economy. For instance, if competition reduces loan rates, the debt burden of bank creditors is automatically lower, mechanically reducing default risk.

Empirical Challenges

While these theoretical considerations are plausible, they have inconsistent predictions and thus leave us confused about the real effects of banking competition. To resolve this issue, we may examine relevant data and carry out empirical tests. However, this is easier said than done. If a highly competitive banking market exhibits strong credit growth, can we conclude that the large number of banks in the market causes credit to grow? The answer is usually no, because unobserved factors, such as prevailing economic conditions and the attractiveness of the market, could boost both bank entry and credit growth at the same time. Hence, in order to identify the causal effects of banking competition, one would need to conduct an experiment and randomly vary entry barriers for banks across different markets that are identical in all other dimensions. There are many reasons why conducting such an experiment is not possible. However, history provides us with a natural experiment on just this topic: bank regulation during the so-called “National Banking Era.”

The National Banking Era

The National Banking Era spans the period between the Civil War and the founding of the Federal Reserve System, roughly 1863 to 1913. It was preceded by what is now referred to as the Free Banking Era, during which banks could charter under state laws after fulfilling a simple set of regulatory requirements. Since the United States did not have a central bank for most of the nineteenth century, these state-chartered banks were the main issuers of notes in circulation. To be able to issue bank notes, banks had to cover their note issuances with purchases of state-issued government bonds. This changed during the Civil War, when the federal government needed to finance the war. To increase demand for federal government bonds, Congress passed two laws (the National Currency Act in 1863 and the National Banking Act in 1864) that allowed banks to be chartered under federal law—thus the name: national banks. Like state banks before them, national banks were allowed to issue bank notes when backed by government bonds. Currency issued by state banks was taxed at a high rate that encouraged banks to adopt national charters and purchase federal government bonds.

Other than issuing currency, national banks operated very much as banks do today, by taking deposits and making loans. However, a few aspects make the National Banking Era a close-to-ideal laboratory for studying banking competition. First, there was very little government interference. For instance, unlike today, there was no insurance for deposits. Moreover, as there was no central bank, there was also no lender of last resort to help banks in a crisis. Thus, we can be reasonably confident that bank behavior was not driven by the anticipation of government support. Second, banks were restricted to operating as unit banks, which meant that each bank could only operate a single branch serving a single location. This implies that competition in banking markets was local, allowing us to compare similar but arguably independent markets at the same time. Finally, capital regulation during the national Banking Era was set up in such a way that it led to variations in entry barriers across different markets.

A Natural Experiment: Variations in Entry Barriers after Census Publications

Capital regulation during the National Banking Era was structured as requirements on the minimum dollar amounts of equity that shareholders had to raise in order to found a bank. Hence, in contrast to contemporary regulatory frameworks such as Basel III, capital requirements at that time did not constrain a bank’s equity-to-assets ratio but instead acted as an entry barrier. Moreover, the minimum dollar amount of equity required to found a bank varied with the population of the town in which the bank was to be located, as determined by the decennial census. For example, opening a bank in a town with more than 6,000 inhabitants required twice the amount of capital investment than would be required in a town with fewer than 6,000 inhabitants. Comparing towns to the right and left of this cutoff allows us to compare towns that are similar in most dimensions, but have different entry requirements for national banks. Therefore, we are able to use changes in the census population that altered the amount of regulatory capital required to start a bank to identify the effects of changes in entry barriers on bank behavior, credit provision, and risk-taking.

Changes in banks’ requirements for start-up capital following a census publication only applied to newly founded banks, and not to incumbent banks. This feature is particularly attractive from the viewpoint of identification, as differential behavior of incumbent banks across markets with different entry barriers can only derive from changes in the requirements for new entrants and not from differential regulatory treatment of the incumbents themselves. Hence, we can isolate changes in incumbent bank behavior stemming from differences in the ease with which new banks can enter and contest the incumbent’s market.

Our identification strategy then exploits the fact that having more or less than 6,000 inhabitants is random, especially if town size is close to 6,000 inhabitants. Hence, we can compare towns that are similar in all dimensions except the entry barriers for national banks.

A Novel Data Source

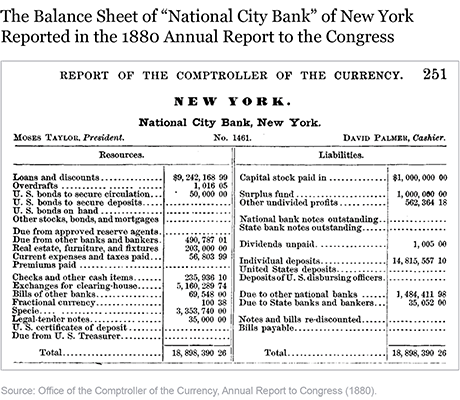

To conduct our investigation, we construct a novel and exciting data set that consists of all national bank balance sheets from 1867 through 1904. The National Banking Act also established a regulatory and supervisory authority, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). The OCC published national bank balance sheets every year in an annual report to Congress (see an example of such a balance sheet below). The data are quite granular and resemble the structure of the regulatory filings that banks and bank holding companies submit today, such as Call Reports and FR Y-9C reports.

We digitized the data by combining optical character recognition techniques with modern layout separation techniques to identify the elements of a table, and created a data set of more than 110,000 annual national bank balance sheets for more than 7,000 unique national banks. As this animated map shows, the banking system grew at a fast pace during this period and expanded toward the West.

Findings

In the research paper that this blog post is based on, we focus on the impact of the publication of the 1880 census as a source of variation in entry barriers. Our analysis reveals that lower entry barriers induce banks to provide more credit. When estimating the effect of increased entry barriers after the census publication, we find that credit growth is around 20 percentage points lower over the next ten years.

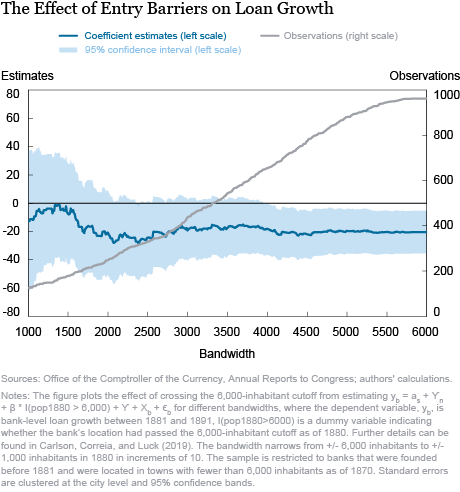

The chart below plots estimates for the effect of an increase of entry barriers on loan growth, together with their 95 percent confidence bands. In the chart, we narrow the bandwidth around the 6,000-inhabitant cutoff from +/- 6,000 (on the very right) to +/- 1,000 (on the left) in increments of 10 inhabitants. The left y-axis measures the estimates and the right y-axis measures the number of observations in the sample within the specified bandwidth. The chart reveals that the effect of entry barriers on loan growth is stable when narrowing the bandwidth. The estimates consistently point to lower rates of loan growth—a decrease of around 20 percentage points—in markets with higher entry barriers. As expected, the estimates cease to be statistically significant (and the confidence bands start to include zero) once the bandwidth and hence the number of observations are sufficiently small. The chart confirms that our results are driven by banks located in towns that are close to the 6,000-inhabitant threshold and are thus driven by banks for which the variation in entry barriers is quasi-random.

In the paper, we provide a number of additional results. We show that while additional credit provision in more competitive markets is associated with higher real economic growth, it is also associated with higher bank risk-taking, since banks in more contested markets were more likely to fail during times of financial distress. In other words, we find that credit growth improves real economic outcomes, but also contributes to the buildup of financial fragility. Our evidence thus offers a causal interpretation of the relationship between credit booms, economic growth, and financial crises.

Mark Carlson is a senior economic project manager at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Mark Carlson is a senior economic project manager at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Sergio Correia is an economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Sergio Correia is an economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Stephan Luck is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Stephan Luck is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Mark Carlson, Sergio Correia, and Stephan Luck, “Once Upon a Time in the Banking Sector: Historical Insights into Banking Competition,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, September 23, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/09/once-upon-a-time-in-the-banking-sector-historical-insights-into-banking-competition.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics