Given momentum in house prices over business cycles, research on consumer beliefs since the financial crisis has honed in on the potential importance of extrapolative beliefs—myopically assuming trends in asset prices will continue. Extrapolation is frequently cited as a central reason for excessively optimistic expectations about future asset prices, featuring prominently, for example, in the irrational exuberance narrative of Shiller. Other influential work since the Great Recession has emphasized the outsized role that extrapolative optimists can have in bubble formation. In this post, we look at how much dispersion there is in the amount of house price extrapolation and how consequential extrapolative beliefs could be for house price dynamics.

To analyze this question, we directly characterize heterogeneity in extrapolation and its relation to “optimistic” beliefs using microdata from a home-price expectation survey. (We’ll refer to price forecasts as more optimistic if they are more positive, but recognize that for a renter looking to buy, high price increases are not necessarily good news.) Whereas most work surveying house price expectations characterizes the determinants of average beliefs, belief heterogeneity is required by many modern models.

If extrapolators are not more likely to participate in the housing market, this suggests that extrapolative beliefs may not be a primary factor in house-price cycles. Preliminary results suggest tremendous variation in the degree of extrapolation across consumers, with the most extrapolative consumers also being the most optimistic. Although this is a necessary condition for extrapolation to feed asset price booms, the most optimistic are not more likely to enter the housing market. This finding suggests that there may not be enough extreme extrapolators in the housing market to justify models that rely on them to move prices and trading volumes.

Our analysis is based on the housing module of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE). Among other things, respondents are asked about their perceptions of past local home price changes, expectations for future local home price changes, past housing-related behavior, their future likelihood of buying a home or investment property, and the main reasons for their anticipated behavior. We use data from 2015-19, the five years in which the relevant questions were asked.

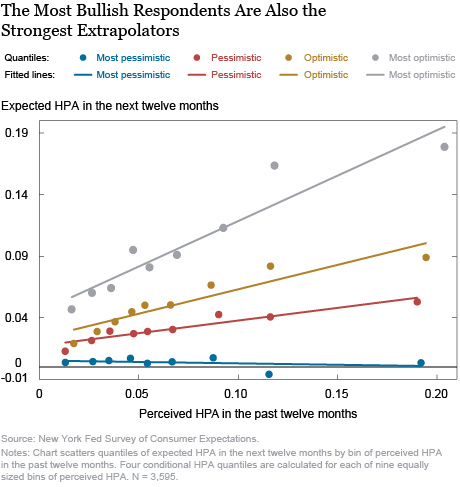

The chart below presents a quantile-binned scatter plot of our two key variables, perceived past home price appreciation (HPA) and expected HPA. The colors reflect the respondent’s expectations of price growth over the next year – gray is the highest at 25 percent, gold next highest, then red and finally blue with the lowest expectations of growth over the next year. We can see that households within different quantiles in the conditional home-price belief distribution extrapolate very differently. The bottom quantile shows close to zero extrapolation (almost no relationship between perceptions of last year and expectations for next year), while the top quantile extrapolates much more than the rest of the population. That is, the steep slope of the gray line indicates that the group with the most positive expectations also expects the future to be the most similar to the past.

The chart above doesn’t control for anything, so it could be driven by other factors, such as location or personal characteristics. To formalize the observations from the chart and estimate how the degree of extrapolation varies over the conditional distribution of optimistic beliefs, we estimate quantile regressions with the conditional distribution of one-year-ahead expected local HPA along the y-axis, and the perceived past local HPA along the x-axis. We also include a rich set of demographic controls, including: binary indicators for owning a home, numeracy, ethnicity, gender, marital status, education, labor force status, Census region, age, age squared; and logs of household income, home equity, and liquid savings. The extrapolation coefficient reports the degree to which a given quantile of expectations depends on an individual respondent’s reported perception of past local HPA. The constant term reflects how optimism—higher expected appreciation not explained by any of the covariates—varies across quantiles of the conditional distribution of expectations. We call the constant term the “baseline optimism coefficient,” because it reflects expected price growth even when perceived past house price appreciation is zero.

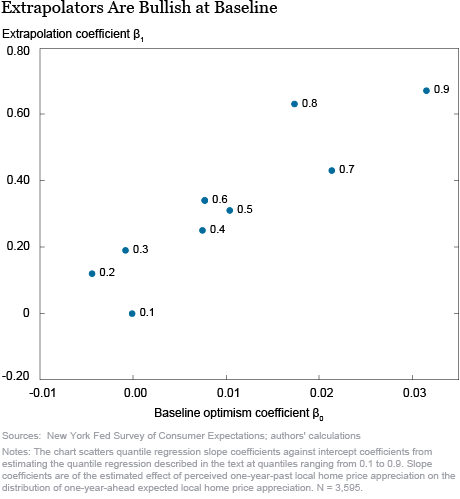

Our first preliminary finding is that there is wide dispersion in the degree of extrapolation, potentially explaining why survey evidence and model calibrations diverge. The next chart plots the slope coefficient against the constant term. A household at the 10th percentile of the conditional home-price belief distribution exhibits virtually zero extrapolation, while a household at the 90th percentile expects house prices to rise 0.67 percentage points for every 1 percentage point of past appreciation.

We also find that there is also significant variation in baseline optimism. Even controlling for the degree of extrapolation and our individual-level controls, those respondents who are the most optimistic expect appreciation next year that is more than three percentage points higher than the appreciation anticipated by observationally similar but pessimistic respondents. Lastly, we find that extrapolation and baseline optimism seem closely related. Extrapolation and baseline optimism move together: the strongest extrapolators are also the most bullish on local house prices even when they perceive zero past appreciation.

So far, we have established that there is significant heterogeneity in households’ degree of extrapolation. Moreover, optimists extrapolate much more than the rest of the population. We close by examining whether optimists are particularly likely to be housing market participants and thereby influence prices.

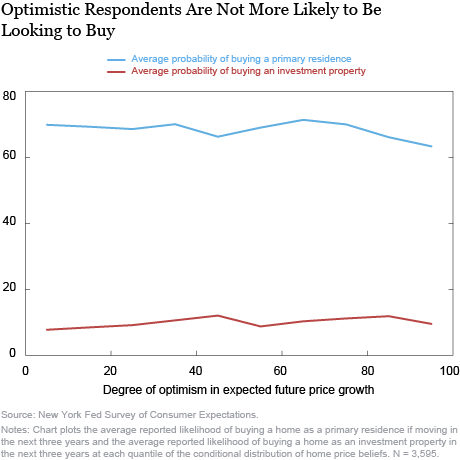

In the chart below, we plot the average reported likelihood of buying next period by optimism level (measured as percentile of the conditional distribution of future HPA). The results suggest limited scope for extreme optimism (and, by extension, extreme extrapolation) to affect house prices. The most optimistic respondents about future prices (top percentiles) are not overrepresented among likely homebuyers (blue line) or investors (red line). While perhaps counterintuitive that the most optimistic respondents do not report being more likely to buy or invest, we find that the most optimistic respondents are also the most likely to cite down payment and income requirements as the biggest inhibitors to purchasing a home.

In conclusion, we find significant heterogeneity in extrapolation from past HPA. Optimists extrapolate twice as much as the median household. Although the relationship between extrapolation and aggregate prices may have been stronger historically, importantly for models of credit cycles going forward, we find that the most optimistic extrapolators from 2015 through 2019 are not more likely to enter the housing market.

Haoyang Liu is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Christopher Palmer is an assistant professor of finance at the MIT Sloan School of Management and a visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

How to cite this post:

Haoyang Liu and Christopher Palmer, “Optimists and Pessimists in the Housing Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 16, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/10/optimists-and-pessimists-in-the-housing-market.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics