Modern-day financial systems are highly complex, with billions of exchanges in information, assets, and funds between individuals and institutions. Though daunting to operationalize, regulating these transmissions may be desirable in some instances. For example, securities regulators aim to protect investors by tracking and punishing

insider trading.

Recent evidence shows that insiders have formed

sophisticated networks

that enable them to pursue activities outside the purview of regulatory oversight. In understanding the cat-and-mouse game between regulators and insiders, a key consideration is the networks that insiders might form in order to circumvent regulation, and how regulators might cope with insiders’ tactics. In this post, we introduce a

theoretical framework that considers network formation in response to regulation and review the key insights.

A Model of Insider Networks

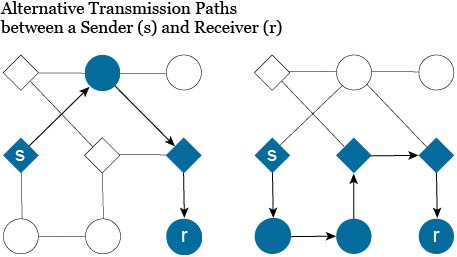

In our model, agents benefit from successfully transmitting a good to others who can utilize it. The good can be a package, a vital piece of information, or even money. To make things concrete, suppose the good is insider information regarding a public company. Agents can form links with each other that allow them to transmit information. Importantly, transfers need not be direct. An insider can transmit the information indirectly through anyone in his network as long as there is a path connected to his co-conspirator. The figure below illustrates how, given a network, a sender can transmit to a receiver along two different paths.

The regulator’s goal is to detect and punish anyone in the network from trading on insider information, as allowing such could ultimately harm market fairness and efficiency. If the regulator could observe and process all transmissions, then he or she could more easily detect insider trading. But observing all trades involves loss of social liberties and privacy, as well as cost for gathering and analyzing large numbers of transmissions.

More realistically, the regulator may know the set of potential insiders, and separately monitor financial markets for that set’s unusual or suspicious trading activity. Knowing the identities of insiders and monitoring market activity is not, however, enough to successfully prosecute wrongdoers. In order to punish violations, the regulator must be able to uncover direct evidence that an individual suspected of insider trading did in fact obtain nonpublic information from another insider. That is, the regulator must be able to map the path of transmission between the sender and the receiver of insider information in order to prosecute the guilty parties. Yet the greater the network distance between the alleged perpetrator and an insider, the costlier it is to identify the link between the two.

The Virtue of Regulatory Ambiguity

Suppose that an insider, call him Isaac, gained insider information, such as news of his firm’s impending merger with an industry competitor. By trading on this information ahead of markets, Isaac could turn a handsome profit. But trading directly is risky. The regulator, who monitors trading activity and knows that Isaac is an insider, would immediately take note. Since it is not hard to verify that Isaac has access to such information, the regulator could swiftly punish Isaac for violating insider trading regulations.

Suppose that the regulator enacts a policy to only take enforcement actions on trading activity by insiders. Isaac could in response relay this information to someone else who takes advantage of it. For instance, he could inform a friend, family member, or business partner who could trade on his behalf, and share the profits. This approach would insulate him and his co-conspirator from prosecution.

But knowing that Isaac is likely to share insider information with his close familiars, what should the regulator do? By expanding the scope of enforcement to include insiders’ friends, family members, and business partners, the regulator can successfully go after Isaac and other insiders who attempt similar schemes. Though expanding the scope is expensive, the regulator would be in a better position to catch all violations.

Can the regulator declare victory? Unfortunately not. Isaac, expecting the regulator to pursue enforcement based on trading activity by his close familiars, can take one step further. By relaying the information down an additional link, such as to an acquaintance of a friend, Isaac can, at a cost of diluting profits, avoid a regulator that only examines close ties. Of course, this likelihood would compel the regulator to increase the scope of enforcement. Following this argument to infinity offers one clear insight: that for any fixed enforcement strategy chosen by the regulator, insiders can successfully profit by transmitting the information along longer chains. Effectively, agents can game the system.

The practice of using long transmission chains to obfuscate the relationship between the sender and the receiver is observed also in money transfers. Money-laundering operations commonly involve “layering” —a practice of transferring through numerous accounts—that obscures a fund’s source from regulators. In the context of capital controls, leaked documents referred to as the “Panama Papers” revealed an extensive network of offshore financial intermediaries and shell companies that helped conspirators evade regulatory scrutiny dating back to the 1970s.

What is the optimal regulation of insider networks?

An effective method for combating gaming is regulatory ambiguity—that is, choosing a policy that is deliberately vague. As long as Isaac does not know with certainty the extent and scope of the regulator’s enforcement intensity, he cannot do “just enough” to escape regulatory prosecution.

Our analysis suggests that authorities benefit from flexible, broad guidelines on which to base regulatory enforcement. Regulatory institutions have been criticized for only loosely defining what constitutes illegal use of insider information. In practice, broad rules governing insider trading have been augmented by courts to ultimately determine illegality on a case-by-case basis. A rationale for using a case-specific approach to determining illegality is clear, in the context of our model: in circumstances where precise regulatory framework necessarily allows for more gaming, agents can easily adjust their strategies to circumvent regulation.

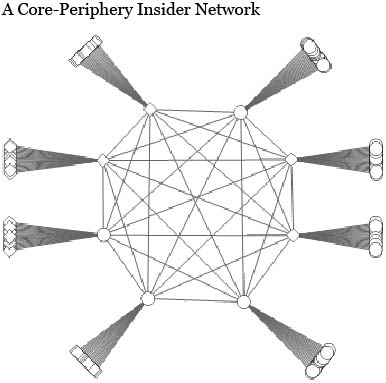

In response to regulatory ambiguity, insiders choose to form flexible core-periphery networks. First, the network is flexible, in the sense that it makes available to insiders multiple paths through which information can be transmitted to another agent in the network. Second, the network takes a core-periphery structure, where agents in the core act as conduits of information on behalf of the periphery members of the network. In doing so, agents form a cost-effective network that ensures that all periphery members have access to a wide set of transmission paths.

How does illegal transmission change with greater regulation?

Empirical studies have found that, historically, insider information has been shared within tight social networks, such as those that involve

familial, social, or geographic ties. Regulatory enforcement in the United States also appears to have become

stronger over time. How might regulation affect the structure of insider networks?

We extend the model so that agents belong to their respective local social networks. When regulatory enforcement becomes sufficiently strong, agents’ information-sharing shifts away from their respective social networks and prompts the formation of more centralized and complex insider networks. These networks consist of intermediaries at the core, who are responsible for matching and relaying information between insiders who are otherwise not connected. The next figure provides an illustrative example of how the highly connected “core” members indirectly connect a large number of “periphery” members.

Expert networks, which have been implicated in insider trading cases in the United States, can be seen as real-life examples. These networks are consulting intermediaries that specialize in connecting clients to experts in various fields—including but not limited to technology, media, medicine, law, and finance—reportedly at rates of up to

$1,300 an hour. Providing clients with access to experts who may own proprietary information, the networks offer a conduit through which nonpublic information can be shared. These intermediaries have become a growing source of information to hedge funds, private equity firms, and other investment firms.

What are the implications for regulatory policy?

Our results suggest that strengthened regulatory and legislative initiatives may trigger demand for, and thereby the creation of, sophisticated networks that connect individuals who otherwise are not connected. Indeed, legislative and regulatory actions may have been

at least partly responsible

for the growth of the expert network industry in recent years. Regulation Fair Disclosure and the Global Analyst Research Settlements, enacted in the early 2000s, tightened governance on information disclosure and restricted insider information dissemination by financial intermediaries, who have

historically been at the center of information diffusion. In the political arena, the Stock Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act (STOCK Act), enacted in 2012, imposed restrictions on profiting from private information derived from Congressional activity. More recently, the European Union rolled out a legislative framework called MiFID II to improve market transparency that, among other things, bans banks from bundling transaction and research services. While these actions may succeed at displacing existing channels of information diffusion, they may prompt the formation of networks that aim at undermining the objective of improving market integrity, posing new challenges for policymakers.

Selman Erol is an assistant professor of economics at Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University.

Michael Lee is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael Lee is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Selman Erol and Michael Lee, “Insider Networks,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 25, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/06/insider-networks.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics