Emerging economies are fighting COVID-19 and the economic sudden stop imposed by lockdown policies. Even before COVID-19 took root in emerging economies, however, investors had already started to flee these markets–to a much greater extent than they had at the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis (IMF, 2020; World Bank, 2020). Such sudden stops in capital flows can cause significant drops in economic activity, with recoveries that can take several years to complete (Benigno et al., 2020). Unfortunately, austerity and currency depreciations as enacted during the global financial crisis will not mitigate this double whammy of capital outflows and policies to cope with the pandemic. We argue that purchases of local currency government bonds could be a viable option for credible emerging market central banks to support macroeconomic policy goals in these circumstances.

Vulnerable Emerging Economies

The pandemic is causing a devastating impact on emerging economies, which are experiencing even more dramatic drops in employment and growth compared to more advanced economies. Commodity-producing emerging economies have seen sharp declines in their export prices (Hevia and Neumeyer, 2020), while others have been hit by the collapse of remittances and tourism. Overall demand for goods and services produced in these countries have collapsed.

Emerging economies face unprecedented challenges stemming not only from the pandemic-induced economic shock but also from their more limited ability to borrow during a crisis. To complicate matters, IMF resources are stretched as several economies face sizeable financial needs (García-Herrero and Ribakova, 2020). There have been efforts at international cooperation and coordination aimed at boosting IMF resources or supporting the debt rescheduling or restructuring proposed by Bolton et al. (2020), but such initiatives might come to fruition too late.

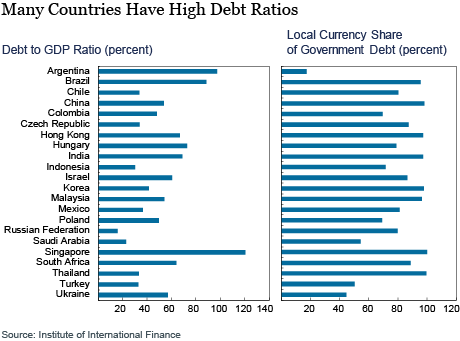

The conventional view is that economies should enact fiscal stimulus to the extent to which their level of government debt allows. However, as seen in the chart below, emerging markets have limited fiscal space, with an average government debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 50 percent at the end of 2019—close to historically burdensome levels for emerging economies. (Note, though, that the high levels seen in Hong Kong and Singapore are a byproduct of their role as financial centers.)

Experimenting with QE

Emerging economies have responded to the pandemic and the resulting sharp global economic downturn by allowing their currencies to depreciate and easing monetary policy, as they did during the global financial crisis. Several central banks have gone further and, for the first time, even before reaching the zero-lower-bound on policy rates, have started to engage in long-term government asset purchases, commonly referred to as quantitative easing (QE)—one of the “unconventional” monetary policy tools employed by advanced economy central banks during the global financial crisis.

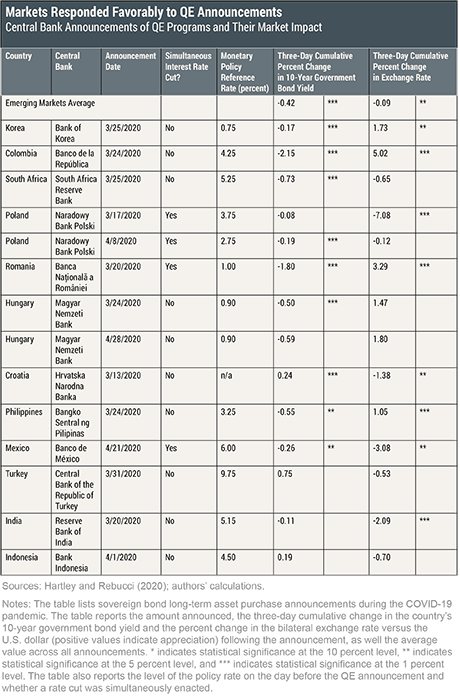

Quite surprisingly, government bond markets and foreign investors have responded quite favorably to these announcements, with long-term interest rates falling significantly in all but three cases (see table below), and exchange rates either appreciating or slowing their depreciation (see table and Arslan et al., 2020).

The Argument for QE

Many emerging economies operate under a flexible inflation-targeting regime, letting their exchange rate float to different degrees, and have long been able to issue sovereign debt in their local currency. This latter critical strength was acquired over the past several years in an attempt to eliminate foreign exchange risk in the government balance sheet. Indeed, local currency bonds now represent the lion’s share of the stock of government debt in these countries, with an average share of local currency debt in total government debt of 79 percent as at the end of 2019 as seen in the top table above.

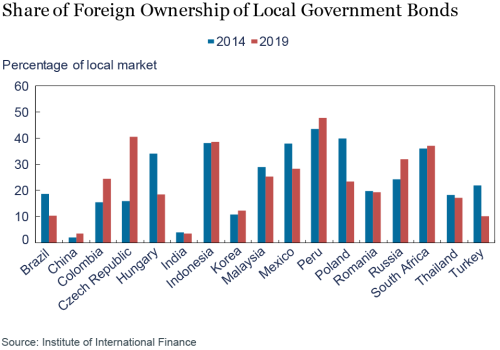

Government bond purchase programs by central banks can restore liquidity in the local bond market during times of crisis, thereby lowering the cost of borrowing for the rest of the economy. This is particularly relevant for economies in which foreign investors hold a significant share of the local currency sovereign debt outstanding as seen in the chart below. These investors’ liabilities tend to be in U.S. dollars, giving rise to currency mismatches in their balance sheets (Carstens and Shin, 2019). As a consequence, a rise in risk aversion can trigger fire sales of local bonds that put pressure on emerging market government bond yields and exchange rates. Emerging market central banks can counter these forces by being purchasers of last resort and preserve liquidity and stability in the local government bond market. Stepping into the market in this manner makes it less likely that foreign investors sell bonds, reducing downward pressure on local asset prices.

We argue that emerging economies with a flexible exchange rate regime and well-anchored inflation expectations should consider the benefits of QE to stabilize financial conditions and help finance the government budget deficit caused by the pandemic. This way, QE programs would help reduce the risk of prolonged stagnation.

The Downside Risks

QE, like any aggressive monetary expansion, poses the risks that the exchange rate depreciates and inflation expectations de-anchor. However, as long as there is abundant slack in the economy, monetary-financed fiscal expansions are unlikely to be inflationary. Inflation is low and stable in many emerging markets, as seen below. In addition, expectations are well anchored, with many more countries with inflation rates within or below target bounds rather than above them. Moreover, large depreciations led only to moderate and temporary bursts of inflation during the global financial crisis, as the exchange rate pass-through had already fallen to levels close to those in advanced economies, as documented, for instance, by Jašová, Moessner, and Takáts (2016).

Economies that have a poorly diversified production base and are heavily dependent on imports for consumption or production purposes will face stronger price pressures from a weaker currency. Hence, the argument for embracing QE for fiscal purposes does need to be qualified, as not all countries will be in a position to use QE without exposing themselves to significant inflation risks.

Finally, another risk associated with QE is related to the extent to which the private sector is exposed to foreign exchange risk (see, for example, Avdjiev, McGuire, and von Peter, 2020). In this case, a sharp depreciation would put pressure on private sector balance sheets, raising the risk of adverse consequence if the asset purchase program causes a significant currency depreciation. Central banks can counter by providing foreign currency to the corporate sector by drawing on their war chest of reserves.

In sum, we argue that QE is a viable macroeconomic policy response to the pandemic for countries with a credible central bank, a floating exchange rate regime, and sovereign debt that is largely denominated in its own local currency. By undertaking such a policy, these central banks could stabilize domestic financial markets and help finance the government spending needed to flatten both the pandemic and recession curves.

Gianluca Benigno is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gianluca Benigno is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jonathan Hartley is a visiting fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

Alicia Garcia Herrero is the chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis.

Alessandro Rebucci is an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School.

Elina Ribakova is deputy chief economist at the Institute of International Finance.

How to cite this post:

Gianluca Benigno, Jonathan Hartley, Alicia Garcia Herrero, Alessandro Rebucci, and Elina Ribakova, “Should Emerging Economies Embrace Quantitative Easing during the Pandemic?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 2, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/10/should-emerging-economies-embrace-quantitative-easing-during-the-pandemic.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics