The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the various measures put in place to contain it caused a rapid deterioration in labor market conditions for many workers and plunged the nation into recession. The unemployment rate increased dramatically during the COVID recession, rising from 3.5 percent in February to 14.8 percent in April, accompanied by an almost three percentage point decline in labor force participation. While the subsequent labor market recovery in the aggregate has exceeded even some of the most optimistic scenarios put forth soon after this dramatic rise, the recovery has been markedly weaker for the Black population. In this post, we document several striking differences in labor market outcomes by race and use Current Population Survey (CPS) data to better understand them.

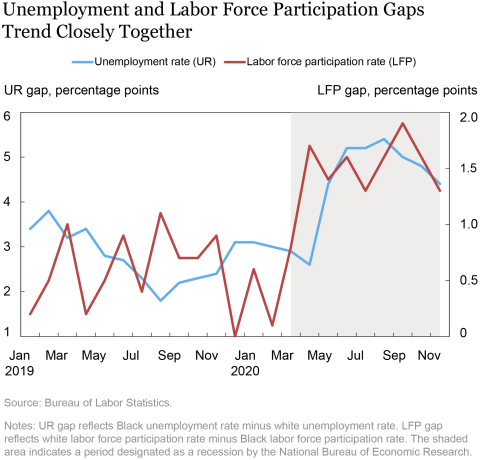

Recessions tend to have disproportionately adverse effects on the labor market outcomes of Black workers. For example, in the years leading up to the Great Recession of 2007-09, the unemployment gap between Black and white workers reached as low as 3.4 percentage points, but it peaked at 8.5 percentage points during the aftermath of the Great Recession. The COVID recession has been no outlier in this regard, as shown in the chart below. The unemployment rate rose significantly more for the Black population, pushing the Black-white unemployment gap from 3 percentage points in February to 5.4 percentage points in August. Similarly, while the long expansion following the Great Recession had narrowed the long-standing Black-white participation gap, the pandemic erased these gains. Participation fell more severely for the Black population at the onset of the pandemic and has since recovered more slowly.

The evolution of the unemployment and labor force participation rates is shaped by flows between employment, unemployment, and being “not in” the labor force. For example, the unemployment rate declines if more people find jobs or fewer workers are displaced. Given that a large share of the unemployed are currently classified as temporarily unemployed (namely, those who have been given a date to return to work or who expect to return to work within six months) and that temporarily and permanently unemployed workers tend to find jobs or drop out of the labor force at very different rates, we distinguish between these two groups in our analysis. We use data from the CPS on individuals age 16 and older, and we compute the rate at which Black and white workers transition between employment (E), temporary unemployment (TU), permanent unemployment (PU), and not in labor force (N).

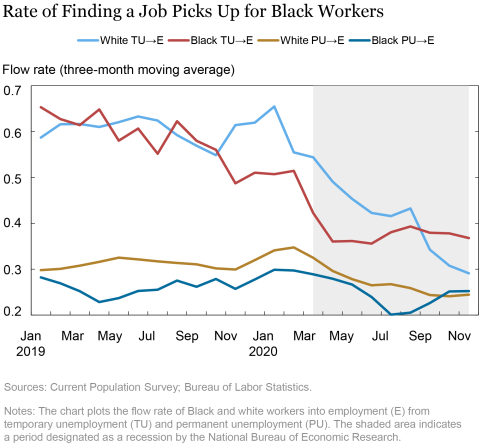

The rate at which workers find jobs out of unemployment has declined for both Blacks and whites this year, with the level of job-finding significantly lower for Blacks until a recent reversal. Breaking down the job-finding rate into transitions from permanent and temporary unemployment clarifies the disparate experiences of Black and white workers (see chart below). Blacks have lower job-finding rates from both permanent and temporary unemployment but have seen a more gradual decline in job‑finding as the recession has progressed. In recent months, the white job-finding rates from both permanent and temporary unemployment have dropped below the corresponding Black job-finding rates. If the current job-finding rates were to continue, all else the same, we would expect a somewhat faster decline in the Black unemployment rate.

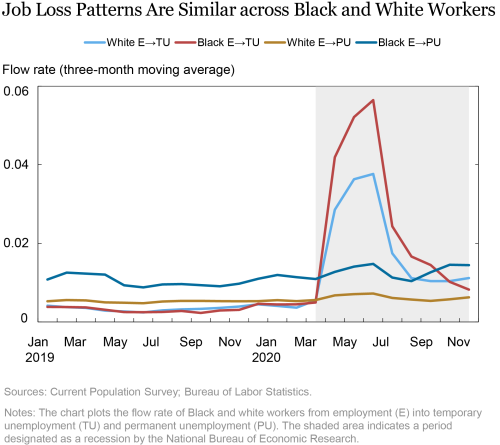

Black and white job loss rates have exhibited a similar pattern. For both Black and white workers, job loss resulting in temporary unemployment peaked in June before declining in recent months, as shown in the chart below. Job loss resulting in permanent unemployment similarly peaked in June. However, for employment loss resulting in both permanent and temporary unemployment, Black workers have experienced significantly higher rates than whites. The Black-white gap in job loss resulting in temporary unemployment widened at the peak of job loss resulting in temporary unemployment, while the gap in job loss resulting in permanent unemployment has been relatively stable throughout the recession.

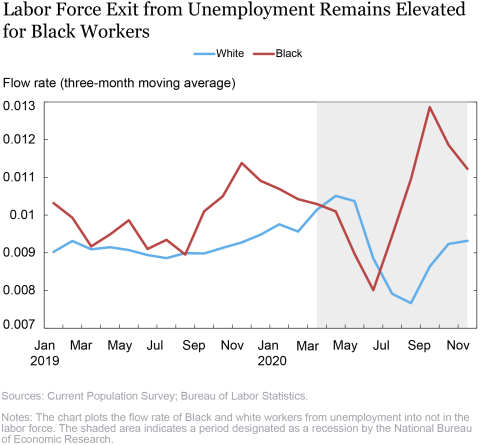

An important feature of the U.S. labor market is that flows out of employment are not always to unemployment; a nonnegligible share of workers drop out of labor force each month. These flows are important determinants of the unemployment and labor force participation rates. Indeed, labor force exit from employment varies significantly for Black and white workers. Until June, the two groups exhibited similar trends as labor force exit from employment dropped. However, in recent months the labor force exit rate for white workers has reverted to pre-pandemic levels, while the labor force exit rate for Black workers has increased dramatically (see chart below). The divergence in Black and white labor force exit rates from employment in recent months suggests that labor force participation for the Black population may remain significantly depressed in the coming months while white labor force participation may recover more quickly, with this combination erasing the gains achieved during the long expansion following the Great Recession.

The COVID recession, like most post-war recessions, has had disproportionate effects on the Black population. We trace the rising and persistent Black-white unemployment and labor force participation gaps to the underlying flows between labor market states. For Black workers, a lower job-finding rate and a higher separation rate into unemployment have contributed to the larger increase and subsequent slower recovery of the unemployment rate. While the job-finding and job-loss rates for Black and white workers have converged recently, resulting in a narrowing of the Black-white unemployment gap, the transition rate from employment into nonparticipation for Black workers remains elevated. This relatively high rate of labor force exit for Black workers may lead to a persistently elevated Black-white labor force participation gap and an uneven labor market recovery.

David Dam is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Meghana Gaur is a senior research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group.

Fatih Karahan is a senior economist in the Research and Statistics Group

Laura Pilossoph is an economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Will Schirmer is a senior research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

David Dam, Meghana Gaur, Fatih Karahan, Laura Pilossoph, and Will Schirmer, “Black and White Differences in the Labor Market Recovery from COVID-19,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 9, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/02/black-and-white-differences-in-the-labor-market-recovery-from-covid-19.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics