The question of how U.S. monetary policy affects foreign economies has received renewed interest in recent years. The bulk of the empirical evidence points to sizable effects, especially on emerging market economies (EMEs). A key theme in the literature is that these spillovers operate largely through financial channels—that is, the effects of a U.S. policy tightening manifest themselves abroad via declines in international risky asset prices, tighter financial conditions, and capital outflows. This so-called Global Financial Cycle has been shown to affect EMEs more forcefully than advanced economies. It is because higher U.S. policy rates have a disproportionately larger impact on rates in EMEs. In our recent research, we develop a model with cross-border financial linkages that provides theoretical foundations for these empirical findings. In this Liberty Street Economics post, we use the model to illustrate the spillovers from a tightening of U.S. monetary policy on credit spreads and on the uncovered interest rate parity (UIP) premium in EMEs with dollar-denominated debt.

Real Effects of U.S. Monetary Policy on EMEs

We start by estimating the effects of U.S. monetary policy on EMEs, using a structural vector autoregressive model (SVAR) model including EME GDP and U.S. variables such as GDP, inflation, unemployment, capacity utilization, consumption, investment, and the federal funds rate for the period 1978:Q1-2008:Q4. The key identification assumption in the SVAR model is that the only variable that the U.S. monetary policy shock affects contemporaneously is the federal funds rate.

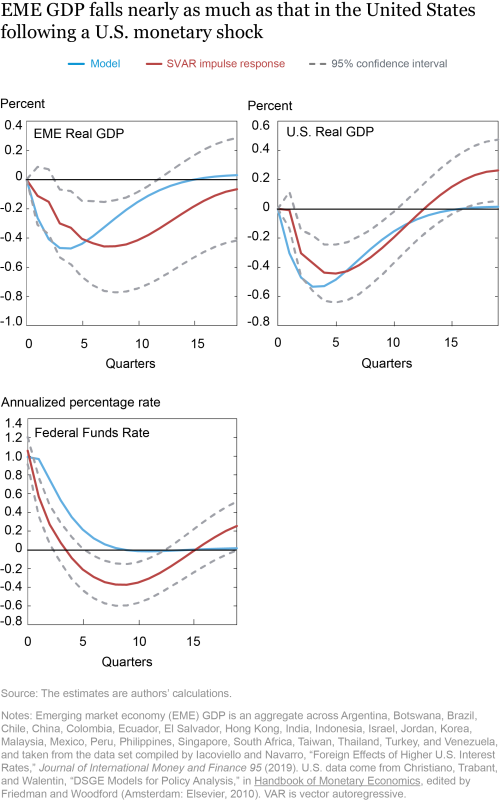

The results are shown the chart below. The red line in each panel indicates the point estimates of the impulse response functions, while the gray dotted lines mark the corresponding 95 percent probability bands. The blue line shows the predictions of our model, where we calibrate the larger economy to the United States, and take the smaller economy to represent a bloc of EMEs, such as the Asian or the Latin American EMEs. Starting with the U.S. economy, the model captures the dynamic response of U.S. output to a U.S. monetary policy shock remarkably well. A monetary policy innovation that raises the U.S. federal funds rate by 100 basis points induces U.S. output to fall around 0.50 percent at the trough, very close in magnitude to those implied by our model.

We next turn to the spillovers to emerging markets. In response to the same shock, EME output falls around 0.45 percent at the trough, broadly comparable in magnitude to the decline in U.S. GDP, and remains below its baseline path well after the effect of the shock on interest rates is gone. Our model captures both the magnitude and the persistence of the response of EME output reasonably well, although the model-implied EME output response is somewhat less sluggish than the SVAR-implied one.

Disentangling Channels of Spillovers

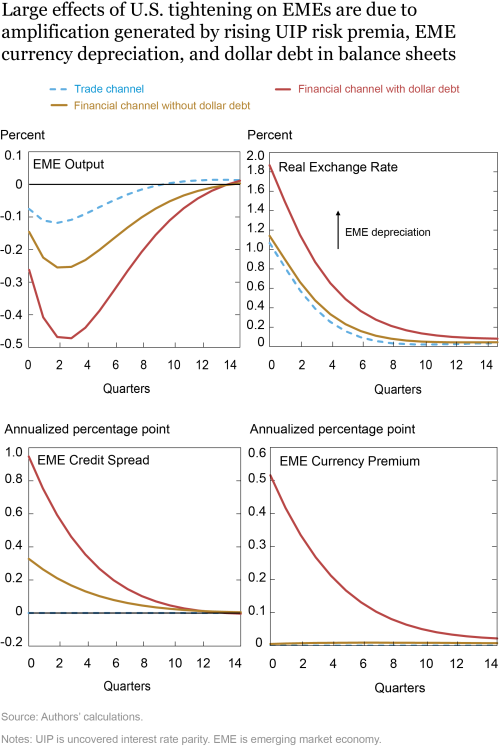

Having shown that the model’s predictions on the spillovers of a U.S. monetary policy shock on EMEs are plausible, we next use it to disentangle channels through which these shocks transmit to EMEs. Our model predicts two channels of transmission: the trade channel and the financial channel. The chart below displays how much EME GDP would be affected through each channel.

The trade channel operates through a fall in EME exports due to lower U.S. demand. This effect is partially offset by EME exports becoming cheaper as the dollar appreciates. Overall, EME output declines by about 0.10 percent relative to baseline due to the trade channel.

The financial channel operates through lower investment spending due to both rising credit spreads and larger UIP risk premia (shown in the lower left and lower right panels of the chart, respectively). Note that UIP risk premia are defined as the difference between the required return by global investors for lending to EMEs (adjusted for expected exchange rate changes) and the return on U.S. safe assets. To highlight the amplification role played by the deviations from UIP, we first shut down this channel (by assuming that UIP holds at all times and that there is no dollar debt in EME balance sheets), and show the predicted effects by the gold lines in the four panels of the chart. The drop in EME asset prices following the U.S. rate hike works to initiate losses in EME borrowers’ balance sheets. Weaker EME balance sheets then give rise to higher domestic lending spreads, making credit more expensive for EME borrowers and triggering declines in investment, and ultimately slowing economic activity. This is the standard financial accelerator effect typically present in models with credit market frictions, causing EME output to fall by an additional 0.15 percent below baseline.

Our model adds an additional amplification mechanism based on the interaction between balance sheets and external financing conditions. Now, the EME’s exchange rate depreciation following the U.S. rate hike causes additional losses in EME borrowers’ balance sheets (over and above the effects of the drop in EME asset prices). This occurs due to the presence of some dollar debt on the balance sheet of these borrowers. Because the assets held by EME borrowers are denominated in the local currency, the depreciation of the local currency against the dollar that occurs in the wake of the U.S. tightening raises the real burden of the dollar debt, thus reducing borrowers’ net worth further. In equilibrium, a weakening of local balance sheets widens the deviation from UIP, which in turn is accommodated via a depreciation of the EME currency against the dollar. Because local balance sheets are partly mismatched, a weaker local currency then feeds back into balance sheet health, further weakening it. The result is sharply amplified declines in the value of EME currency and investment, more than offsetting the positive effect of depreciation on EME exports, that brings total decline in EME output to 0.45 percent relative to baseline.

Testing the Link between UIP Deviations and Financial Stress

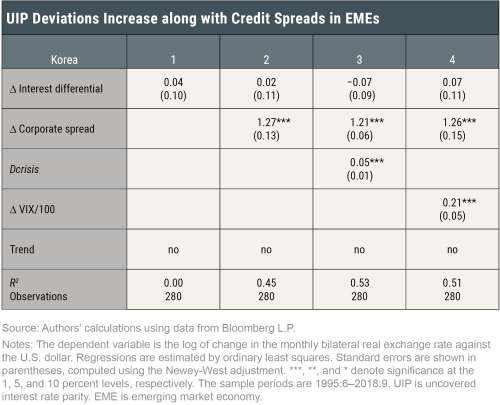

The model features a time-varying UIP risk premium that increases with the domestic lending spreads in EMEs. We test this prediction of the model using data from Korea and present the results in the table below.

The second column shows our results, where we regress the change in real exchange rate on the changes in the interest differential and the corporate bond spread. We find that the coefficient on the spread is highly statistically significant, and the presence of the spread improves the fit considerably. In the third and fourth columns, we include an indicator variable for the crisis periods, which takes unity in the months 1998:8–1999:3 and 2008:9–2009:3, and zero otherwise, and a measure of global risk aversion (proxied by the VIX), respectively. As shown, the coefficient on the spread continues to be significant, lending support to the mechanism we propose in the model.

In sum, we present a model where the effects of a U.S. monetary policy shock on EMEs are amplified due to UIP premia that are correlated with domestic lending spreads, consistent with the evidence. Our research provides theoretical foundations for the Global Financial Cycle that shows monetary contractions in the United States lead to tightening of foreign financial conditions, and for more recent findings that show these effects are larger in EMEs than in advanced economies.

Ozge Akinci is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Albert Queralto is a principal economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Albert Queralto is a principal economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

How to cite this post:

Ozge Akinci and Albert Queralto, “How Does U.S. Monetary Policy Affect Emerging Market Economies?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 17, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/how-does-us-monetary-policy-affect-emerging-market-economies.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics