The fiscal packages passed in 2020 and 2021 to help the economy cope with the pandemic caused a dramatic increase in federal government borrowing. One might have expected that foreign investors were important buyers of this new debt, but that was not the case. They were instead net sellers of Treasury securities. Still, the amount of money flowing into the United States increased last year, which helped fund the government’s borrowing, if only indirectly. The upturn in inflows, though, was quite modest as a surge in domestic personal saving largely covered the government’s heightened borrowing needs. How the reliance on foreign funds changes in 2021, when the government deficit will again be quite elevated, will depend on whether domestic personal saving remains high.

Foreign Purchases of U.S. Government Securities

Federal government actions during the pandemic caused a surge in the amount of federal debt outstanding. Specifically, the level of U.S. government marketable debt held by the public, pulled from the Treasury’s Statement of the Public Debt, rose by $4.3 trillion over the course of 2020, climbing from $16.7 trillion to $21.0 trillion. For comparison, this measure of debt increased by $1.1 trillion in 2019.

Balance of payments data show that foreign investors did not step in to buy this additional debt. Instead, they were net sellers of federal government securities, to the tune $75 billion. This was a change from being net buyers of $226 billion of these securities in 2019. Foreign investors were interested in other assets, with cross-border financial inflows going toward purchases of equities and investment funds ($726 billion) and corporate bonds ($194 billion).

Considering just Treasury securities in examining the role of foreign investors, though, misses the more important question of how much financial inflows rose to help fund the U.S. economy. From this perspective, increased foreign investment in U.S. assets created a pool of money that would not have been there otherwise, indirectly supporting sales of Treasury securities.

Government Saving versus Personal Saving during the Pandemic

One way to connect the change in the budget deficit with the change in borrowing from abroad is to rely on national income identities. Start with the notion that someone’s spending is another person’s income. To simplify the discussion, assume the U.S. economy is closed to the rest of the world so that domestic spending always equals domestic income. Spending can be broken down into consumption and physical investment spending and income can be broken down into consumption and saving. Consumption is the same for both identities, so you are left with the identity that investment spending must equal domestic saving.

Removing the assumption of a closed economy allows for a country to borrow from the rest of the world or lend depending on the difference between its saving and investment spending. In the case of the United States, the economy borrows from the rest of the world because domestic saving is insufficient to finance investment spending. For financial markets, this plays out as follows: the amount of cross-border financial inflows (for example, to buy Treasury securities) exceeds financial outflows from U.S. investors buying foreign assets by the amount determined by the domestic saving-investment spending gap.

To see what happened to U.S. borrowing in 2020, we break down U.S. saving into public (federal government, state and local government) and private (personal, business) components. (Note that government saving is not the same as the budget deficit because the saving calculation considers the difference between government income and consumption and does not include the government’s investment spending.)

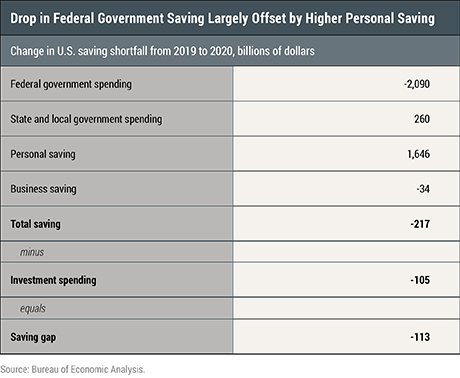

The table below shows how all these components fit into the saving-investment spending framework. There was a $217 billion decline in saving in 2020 relative to the 2019 level, with a huge deterioration in federal government saving mostly offset by a jump in personal saving and a more modest increase in state and local government saving. Adding in a decline in investment spending ($105 billion) leaves the saving gap only $113 billion wider than it was in 2019. (The United States borrowed $503 billion in 2019.) Put another way, 90 percent of the $2.1 trillion decrease in federal government saving in 2020 was offset by increases in other sources of domestic saving and lower investment spending.

From this perspective, foreigners helped offset the increase in federal government dissaving, but the scale of their contribution was modest.

What to Look For Going Forward

The fiscal support packages passed in December 2020 and March 2021 will substantially increase the amount of Treasury debt again this year. So, will the pace of net foreign investment continue to be relatively stable? Unfortunately, while the saving-investment spending framework is useful for understanding what happened, it is less useful in predicting what will happen going forward. It is just an identity, after all, and offers no insights about the interactions between the various forms of saving and the economy.

One is thus left to speculate. A retreat in state and local saving and an increase in investment spending would seem to be in the cards, judging by their levels last year relative to pre-pandemic times. Both developments would increase foreign borrowing.

The table above, though, suggests that the most important unknown is whether personal saving will again offset high federal government dissaving. Consider two extreme outcomes. In one case, consumers take the “extra” saving accumulated in 2020 as an increase in their wealth and do not let it affect their spending behavior. As a result, personal saving remains high this year, again boosted by government transfer payments, and there is little effort to spend down this accumulated savings going forward. The other extreme has consumers running down the extra savings when the pandemic eases over the course of the year and spending rises to match income. The flow of personal saving then disappears and the economy’s reliance on foreign financial inflows jumps.

A further complicating factor in anticipating how this plays out is that the amount of U.S. borrowing has to be equal to the sum of net lending by the rest of the world. Essentially, any increase in the U.S. saving shortfall has to be matched by a bigger saving surplus elsewhere and the mechanism that makes this identity hold has very unclear implications for exchange rates and global asset prices.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Thomas Klitgaard, “Is the United States Relying on Foreign Investors to Finance Its Bigger Budget Deficit?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 21, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/is-the-united-states-relying-on-foreign-investors-to-finance-its-bigger-budget-deficit.html

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Excellent article!!! What role did QE play in this?