The services sector was hit hard during the COVID-19 pandemic. Small businesses were particularly affected, and many of them were forced to close. We examine the state of these firms using micro data from Homebase (HB), a scheduling and time tracking tool that is used by around 100,000 businesses, mostly small firms, in the leisure and hospitality and retail industries. The data reveal that 35 percent of businesses that were active prior to the pandemic are still closed and that most have been inactive for twenty weeks or longer. We estimate that each additional week of being closed reduces the probability that a business reopens by 2 percentage points. Moreover, an additional week of business closure lowers the share of workers that are rehired at reopening. Our estimates imply that only about 4 percent of the workers that are still laid off from the currently closed businesses will eventually be rehired by these businesses.

A Large Share of Small Businesses Remain Closed

We select our baseline sample of businesses as those that were active prior to the beginning of the pandemic and that are regular users of HB. Since businesses need to actively use the HB app to be recorded, firms can churn in and out of the data. To remove these marginally attached firms, we follow earlier work and select all businesses that satisfy one of two conditions: (i) the business was active during a consecutive three-week period starting on February 2, 2020; (ii) the business was temporarily inactive during that period but had at least three active weeks prior to and after this reference period. A business is “active” if it recorded positive employment and at least 40 total hours worked in a given week.

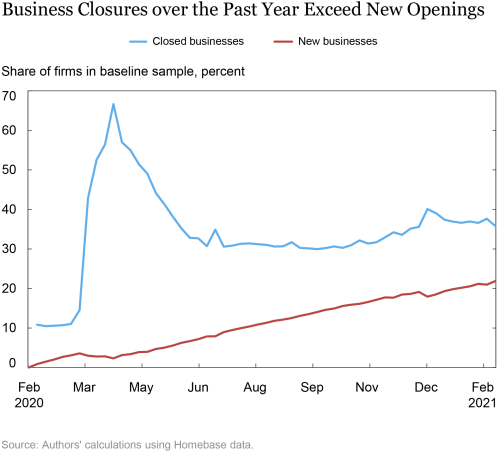

The blue line in the chart below shows that the share of closed businesses has stabilized at around 35 percent of the baseline sample, where a closed business is one that reports zero hours worked or is not in the sample for at least two consecutive weeks. The number of closed businesses peaked in early April 2020 at around 60 percent of all small businesses in HB, fell to about 30 percent by mid-June, and then increased again in December. These closures have so far not been offset by the entry of new businesses, as illustrated by the red line. We define new businesses as those that appeared for the first time after February 9, 2020 and were active for at least three consecutive weeks. Since entry rates are defined based on usage of the HB app, they may exceed true business creation. We therefore keep only businesses that enter the data with fewer than ten employees. The chart shows that the number of such businesses has been growing slowly to about 20 percent of the firms in our baseline sample. Overall, there is still a substantial gap in the number of businesses relative to the pre-pandemic period.

The HB data indicate that, relative to our baseline sample, business closures led to a decline in small business employment of about 40 percent in April 2020. This was more than twice as much as the decline in employment at businesses that did not close. While employment has partially recovered as businesses reopened, currently closed businesses still account for a 25 percent drop in employment relative to February 2020.

Our results point to a slow recovery of the small business services sector, with a substantial fraction of businesses still closed. This finding is consistent with the U.S. Census Bureau Small Business Pulse Survey. Based on that survey, the share of small businesses closing permanently in February and March 2021 was about 1.8 percent per week, compared to reopenings of about 2.1 percent of businesses.

Most of the Still-Closed Businesses Have Been Closed Since the Start of the Pandemic

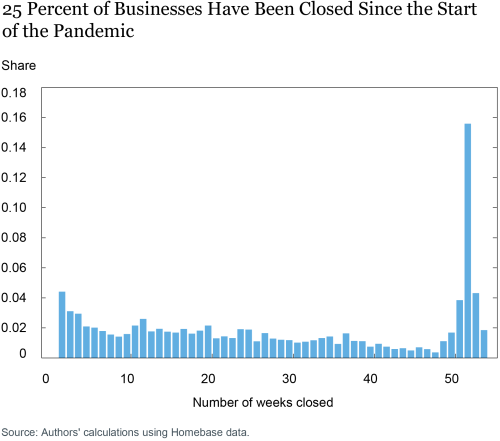

Most of the still-closed businesses have been inactive for twenty weeks or longer. The next chart shows the distribution of businesses from our baseline sample that were still closed in the week starting March 14, 2021. As above, we require a business to be inactive for at least two consecutive weeks to be considered closed to eliminate churn. The chart shows that 25 percent of businesses currently closed have been inactive since March 2020. Moreover, 62 percent of businesses have been closed for more than 20 weeks.

Businesses that Have Been Closed for Longer or that Closed in March Are Less Likely to Reopen

Why have so many small businesses not come back? We investigate this question by examining how reopenings depend on observable factors. We also analyze how these factors affect the number of workers businesses rehire when they reopen. We then use these observables to predict what fraction of laid-off workers are likely to be rehired.

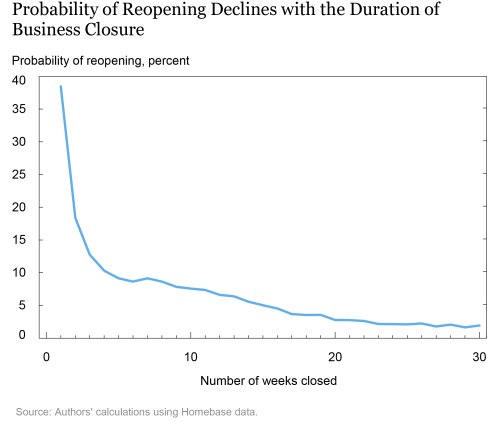

Businesses that remain closed for a long time may lose firm-specific capital, for example due to depreciating entrepreneurial qualities or a deteriorating customer base. Moreover, closed businesses may still have to incur fixed costs that are difficult to evade quickly (long-term rental contracts, for example). The longer a business stays closed, the more likely its net present value turns negative. To test this hypothesis, the chart below plots the probability that a business reopens in a given week conditional on having been closed for a certain number of weeks. We find that this hazard rate of reopening declines significantly with the number of weeks a business has remained closed. The hazard rate drops sharply in the first three weeks, potentially highlighting the importance of business churn at high frequency. Nevertheless, the fact that the probability of reopening declines even at longer horizons suggests the importance of channels other than churn. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis.

While the analysis of duration dependence pools together all businesses that closed any time since March 2020, businesses that closed early in the pandemic differ in their reopening probability from those that stayed open for longer. We find that businesses that closed in July of 2020 are around 5 percentage points more likely to reopen than those that closed in March, regardless of the length of the closure. One possible explanation for this finding could be that aggregate conditions hit exiting firms hardest in March, making a comeback more difficult. Moreover, time effects could play a role: closing in March implies that a business had to wait longer before aggregate demand conditions improved.

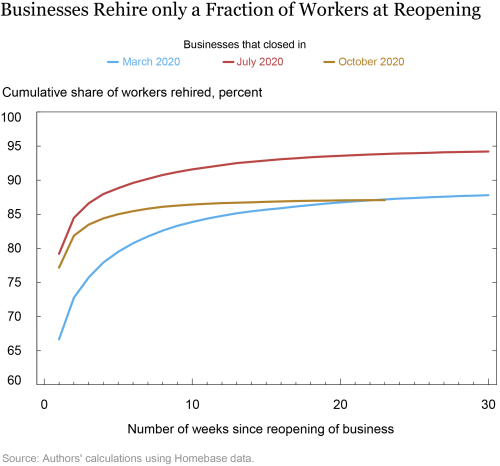

We next investigate what share of workers laid off at the time of the business closure is rehired at reopening. The chart below displays the cumulative “rehiring share” over time since reopening, for businesses that closed in March (blue line), July (red line), and October (gold line) of 2020. About 70-80 percent of the workers terminated at closure are immediately rehired upon reopening, as indicated by the lines at week 1. Businesses keep recalling more workers over time, but the speed at which this rehiring takes place also decreases with the time since reopening. In general, the trajectories differ by month of reopening. Businesses that closed in July rehire a larger share of their workforce than businesses that closed in October or March 2020. We note that since some businesses never reopen, their workforce is never rehired.

We can quantify these relationships more formally using a panel regression. The regression also takes into account the role of business size and industry heterogeneity. We find that each additional week of business closure reduces the probability that a business ever reopens by about 2 percentage points. Moreover, businesses that closed after March 2020 have a higher probability of reopening by about 12 percentage points compared to businesses that closed in March. Larger businesses are also slightly more likely to reopen. Finally, for those businesses that reopen, each additional week of being closed reduces the number of workers rehired at reopening by 5 percent.

Only a Small Share of Closed Businesses Are Likely to Reopen

We can use the regression estimates to predict the fraction of the currently closed small businesses we expect to eventually reopen and the fraction of their workers we expect to be rehired. Based on our regression estimates, we expect only about 3 percent of currently closed businesses to reopen, and we expect these reopening businesses to rehire about 35 percent of their laid-off workers over four weeks. Combining the probability of reopening and the rehiring share for each currently closed business and summing across the distribution, we estimate that only about 4 percent of the workers of the currently closed businesses will eventually be rehired.

This prediction could be affected by many factors. On the one hand, it could under-predict the true extent of rehiring because our regression is estimated on a period in which economic activity was depressed. If aggregate demand improves in the future, more businesses might reopen. On the other hand, our estimates could over-predict the extent of rehiring because the most viable establishments could be the ones that already reopened. In that case, the current pool of closed businesses could be lower quality than average, leading us to over-predict reopenings if aggregate conditions remain unchanged.

David Dam is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

David Dam is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sebastian Heise is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sebastian Heise is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Davide Melcangi is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Davide Melcangi is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Will Schirmer is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

David Dam, Sebastian Heise, Davide Melcangi, Will Schirmer, “Many Small Businesses in the Services Sector Are Unlikely to Reopen,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 05, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/many-small-businesses-in-the-services-sector-are-unlikely-to-reopen.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics