This post presents an update of the economic forecasts generated by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model. We describe very briefly our forecast and its change since March 2021. As usual, we wish to remind our readers that the DSGE model forecast is not an official New York Fed forecast, but only an input to the Research staff’s overall forecasting process. For more information about the model and variables discussed here, see our DSGE model Q & A.

Estimating the Model taking the Pandemic and the New Monetary Policy Framework into Account

The key drivers of the model’s forecast remain the responses of the economy and policy to the COVID-19 pandemic. The model’s parameters are different than those used to produce the March projection in that the model has now been re-estimated, incorporating data up to 2021:Q1. In addition to changing the posterior distribution of the parameters, the estimation exercise provided the opportunity to evaluate the different scenarios for modeling the dynamics of the economy during the pandemic that we considered over the past year. As a result of this work, we coalesced on one specification. This specification features several transitory demand and supply shocks starting in 2020:Q1: these shocks capture the very large but relatively short-lived macroeconomic effects of the virus (the model description on the GitHub page describes the modeling of the pandemic in some detail). As we described in previous posts, the demand shocks are modelled as discount rate shocks that affect intertemporal consumption decisions, while the supply shocks affect both total factor productivity and labor supply. Starting in 2020:Q2, the COVID-19 shocks are also partly anticipated one quarter ahead, to capture the fact that the pandemic has been persistent and has been expected to be so since shortly after its inception, albeit with an uncertain duration. While for past forecasts the standard deviations of the pandemic shocks were drawn from a prior distribution, now they are estimated, thereby letting the data settle the relative importance of shortfalls in supply or demand in driving the decline in economic activity.

In March, the model’s forecast consisted of two scenarios. In the first one, the importance of standard business cycle dynamics was forcibly limited during the pandemic period, while in the second scenario it was not. The first scenario, which had a weight of 70 percent based on the February 2021 Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) consensus density forecast, had stronger output and weaker inflation projections than the second one. Under the new model specification, the standard business cycle shocks still play a role during the pandemic. A key difference with the second scenario, however, is that their standard deviations—and therefore their relative importance—are allowed to differ from their counterparts during normal times and are also estimated.

In the new model specification we continue to assume that starting in 2020:Q4 monetary policy follows the new average inflation targeting (AIT) reaction function, reflecting the changes in the FOMC monetary policy strategy announced last August. The parameters of the new rule are such that the policy rate lifts off the effective lower bound (ELB) in 2023, increasing very gradually thereafter. Upon its introduction, we assume that agents’ awareness of the new policy is only partial, and that it increases over time. More specifically, expectations are based on a convex combination of the old and new reaction functions, with the weight on the latter converging to 1 over six years. This modeling approach captures the fact that expectations are likely to adjust only gradually to the introduction of the new policy strategy, partly since agents cannot directly observe policymakers’ reaction to macroeconomic developments while the policy rate is stuck at the ELB. (Again, please see the model description on the GitHub page for more detail.)

How Do the Latest Forecasts Compare with the Ones from March?

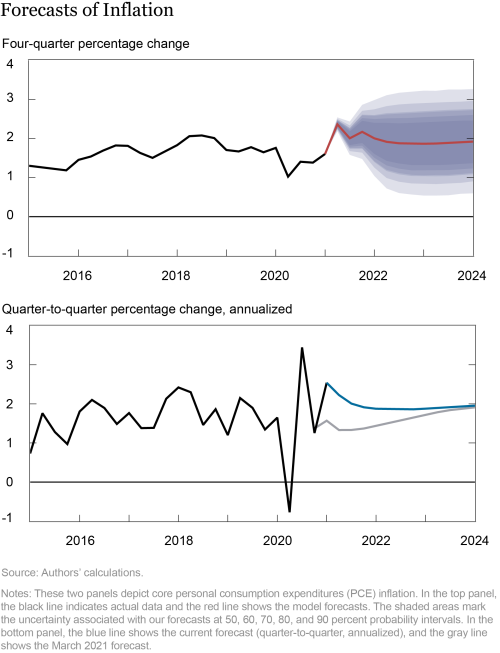

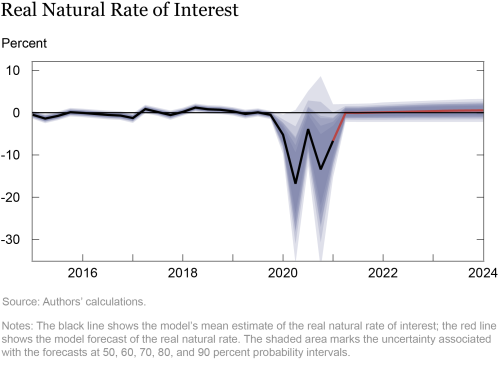

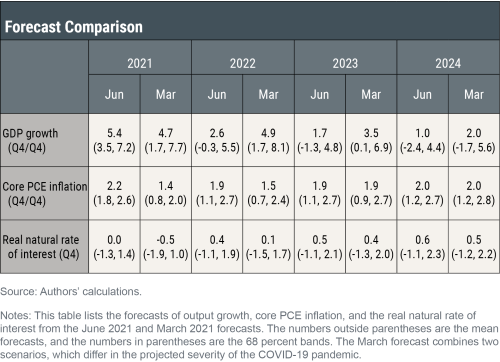

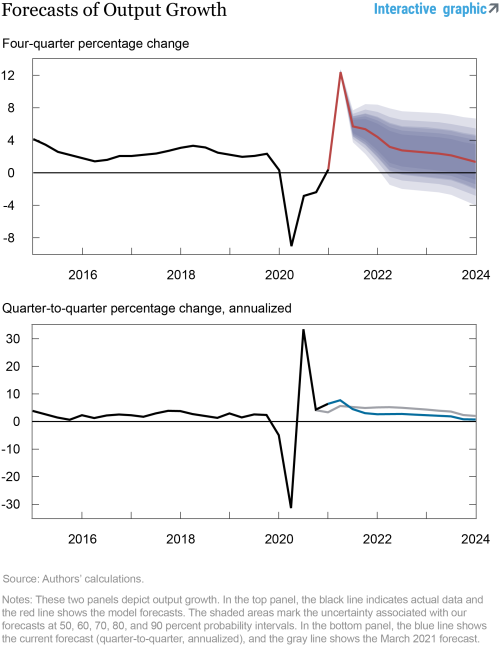

The June 2021 model forecast is reported in the table below, alongside the one from March, and depicted in the following charts. The forecast is based on quarterly macroeconomic data released through 2021:Q1, augmented for 2021:Q2 with the median forecasts for real GDP growth and core PCE inflation from the May SPF release, as well as the yields on 10-year Treasury securities and “Baa” corporate bonds based on 2021:Q2 averages up to June 1.

The change in the forecast relative to March is determined by two factors. One is the new data released over the past three months, and the other is the change in the model parameters and the model specification. The new data on economic activity and inflation were upside surprises. The new posterior distribution, and especially the new model specification lead ceteris paribus to weaker output and stronger inflation forecasts relative to the 70/30 combination of the two scenarios, as the new specification is closer to the second scenario in terms of predictions. These changes result in output projections that are slightly stronger in the short run but weaker in the medium run, and much stronger inflation projections, relative to March.

• Specifically, the mean forecast for real GDP growth (Q4/Q4) is 5.4, 2.6, and 1.7 percent in 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively, compared to 4.7, 4.9, and 3.5 percent in March.

• Core inflation is projected to reach 2.2 percent in 2021, well above the March forecast of 1.4 percent. The model interprets this increase as partly temporary and predicts core inflation to be 1.9 percent in 2022 and 2023. This forecast is stronger than what was predicted in March for 2022 (1.5 percent), but similar for 2023 and 2024 (1.9 and 2.0 percent, respectively).

• The uncertainty surrounding the projections for all variables remains sizable but is mechanically smaller than in March since the projection then involved the combination of two scenarios. The 68th percentiles for the core PCE inflation projections remain below 3 percent throughout the forecast horizon.

• Estimates of the real natural rate of interest and its future evolution are higher than in March, with the natural rate being about 0 percent at the end of 2021 and rising to 0.6 percent by the end of the forecast horizon.

William Chen is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

William Chen is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Del Negro is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Del Negro is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Shlok Goyal is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Shlok Goyal is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Alissa Johnson is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

William Chen, Marco Del Negro, Shlok Goyal, and Alissa Johnson, “The New York Fed DSGE Model Forecast—June 2021,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 18, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/06/the-new-york-fed-dsge-model-forecastjune-2021.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics