Banks monitor borrowers after originating loans to reduce moral hazard and prevent loan losses. While monitoring represents an important activity of bank business, evidence on its effect on loan repayment is scant. In this post, which is based on our recent paper, we shed light on whether bank monitoring fosters loan repayment and to what extent it does so.

An Identification Challenge

From an empirical perspective, assessing the causal effect of bank monitoring on loan outcomes is challenging for two main reasons. First, bank monitoring is difficult to measure, as it encompasses a range of activities that are usually unobservable. These include collecting information on borrowers’ ability to meet the repayment schedule, analyzing the financial reports of a business, keeping track of checking account activity and credit line usage, and collecting soft information from the managers of a firm. Second, a bank is likely to monitor more closely a borrower when the repayment prospects of a loan worsen, thus (mistakenly) suggesting a negative effect of monitoring on repayments. This means that the benefits of bank monitoring cannot be quantified by simply comparing the repayment performance of monitored versus non-monitored borrowers.

In our analysis, we use granular information on business loans extended in Italy by small regional banks to firms and construct a novel proxy for bank monitoring. Our proxy is the number of requests for information made by banks on their existing borrowers to the Italian Credit Register, the national credit reporting institution. The information shared in credit bureaus is crucial for banks to properly evaluate the risk profile of their borrowers. For the Italian Credit Register, a single request provides information on the amount of loans granted by other banks to a firm, as well as on the objective conditions of deterioration of each individual exposure. To capture monitoring activity exclusively, we consider only requests for information made by banks on their existing borrowers that are not associated with the extension of new credit and are not related to exceptional circumstances, such as in the aftermath of a bank merger or acquisition. While banks can monitor borrowers in many other ways—for example, by analyzing a firm’s financial reports, conducting site visits, talking with a firm’s managers, and requesting third-party valuations—our proxy is not intended to quantify all of these activities. Rather, the intention is to capture a bank’s decision to take a closer look at one of its borrowers.

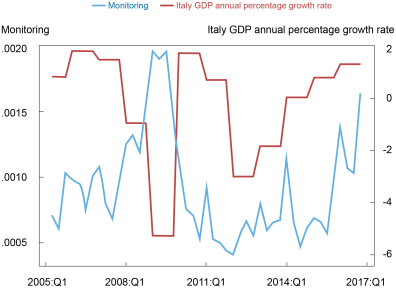

We find that banks monitor more intensely in periods of economic downturns in our sample period. The average number of requests for information per client made by banks correlates negatively with Italy’s annual GDP growth and reaches its historical peak during the great recession (see the chart below). Banks are more likely to monitor when borrowers are risky (that is, those with lower credit rating) and opaque (that is, those with a short credit relationship with the bank). Only a small portion of banks’ requests for information is related to nonperforming loans, meaning that banks primarily monitor with the intention of preventing firms from missing their repayment schedule.

Bank monitoring correlates negatively with GDP growth, peaking in the Great Recession

Note: This chart depicts the time series of the average number of requests for information per borrower made by banks in our sample (left y-axis) along with the annual percentage growth rate of Italian GDP at market prices (right y-axis).

Quantifying the effects of bank monitoring on loan repayment

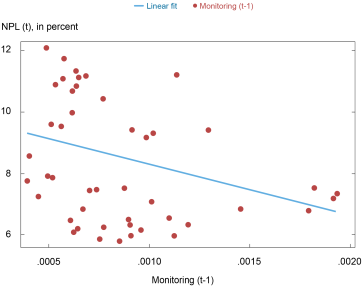

A simple visual analysis shows that the number of requests for information is negatively related to the future probability of a delinquency (see chart below). This negative correlation, though, might be biased upward as banks are likely to monitor more closely the credit exposures that are more likely to become overdue. While this result suggests that bank monitoring may have a positive effect on loan repayment, it does not establish causality, as we discussed earlier.

Bank Monitoring and Nonperforming Loans

Note: This chart depicts the percentage of nonperforming loans in each quarter (“% NPL” at time “t” on the y-axis) against the average number of requests for information per borrower submitted by banks one quarter before (“Monitoring” at time “t-1” on the x-axis) along with a linear fit.

To establish the causal impact of bank monitoring on loan outcomes, we need to identify a driver of bank monitoring that is unrelated to the attributes of the borrower and the conditions of the loan. We argue that a factor satisfying those requirements is taxation. In particular, we demonstrate that changes in the corporate tax rate applied to banks affect their incentives to monitor borrowers. If the corporate tax rate is 100 percent, meaning that all bank profits flow to the state and nothing is left for bank shareholders, banks have no incentives to monitor as this would not have an impact on their shareholders’ value. Conversely, banks have the strongest monitoring incentives when the corporate tax rate is 0 percent. An Italian corporate tax named “Imposta Regionale Attività Produttive” (IRAP) imposes a tax on banks that varies across regions. Consequently, small local banks are usually tied to the IRAP tax rate of the region in which they operate and this is exactly the reason why we focus on small regional banks. Everything else equal, banks operating in regions with a higher IRAP tax rate are more likely to monitor borrowers than banks located in regions with a lower tax rate.

We study firms having multiple credit relationships with small banks which operate at the regional level and are subject to the same or different tax rates. Then, we estimate the effect of bank monitoring on loan repayment by comparing the repayment performance of a given borrower on different loans granted by different banks at the same point in time. To understand our empirical strategy more clearly, consider the example of a firm that borrows contemporaneously from two banks. Bank 1 is located in region A and it is subject to a tax rate XA, whereas bank 2 is located in region B and it is subject to a tax rate XB, with XA greater than XB. Keeping all relevant firm conditions equal, and after accounting for loan and bank characteristics, we expect bank 2 to monitor more intensively than bank 1, implying that the firm is more likely repay the loan(s) granted by bank 2 compared to the loan(s) granted by bank 1.

Bank monitoring has a positive effect on loan repayment

We find that a decrease in the tax rate is associated with greater bank monitoring. A half percentage point decrease in the tax rate (equivalent to almost one standard deviation in our sample) implies an increase in the number of requests for information that corresponds to twice its sample average. More important, we show that monitoring has a positive effect on loan repayment from two to three quarters after a bank’s request for information, with the strongest effect occurring over a two-quarter horizon. The economic magnitude is substantial: an increase in the number of requests for information associated with a decrease in the tax rate by half a percentage point reduces the probability that the credit exposure becomes nonperforming by 2 percentage points two quarters ahead. This result is significant in economic terms given that the probability of a delinquency is roughly 11 percent in our sample.

Bank monitoring should be more effective in fostering loan repayment in the case of term loans. In fact, medium to long-term investments, which are typically funded via term loans, represent the business activities that benefit the most from bank oversight. Indeed, we find that the positive effect of bank monitoring on loan repayment is stronger for term loans vis-à-vis credit lines and loans backed by accounts receivable, consistent with the idea that bank monitoring is more effective in disciplining borrowers in the case of term loans.

Our findings have two key economic implications. First, the effects of bank monitoring are substantial. Monitoring is valuable for individual banks, as it reduces delinquency rates. Second, factors that affect banks’ earnings (such as taxation) also change their incentives to monitor borrowers in a significant way.

Nicola Branzoli is an economist at the Financial Stability Directorate of the Bank of Italy.

Fulvia Fringuellotti is a financial research economist in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Nicola Branzoli and Fulvia Fringuellotti, “Does Bank Monitoring Affect Loan Repayment?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, December 2, 2022, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/12/does-bank-monitoring-affect-loan-repayment/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics