Are policies aimed at fighting climate change inflationary? In a new staff report we use a simple model to argue that this does not have to be the case. The model suggests that climate policies do not force a central bank to tolerate higher inflation but may generate a trade-off between inflation and employment objectives. The presence and size of this trade-off depends on how flexible prices are in the “dirty” and “green” sectors relative to the rest of the economy, and on whether climate policies consist of taxes or subsidies.

A New Age of Energy Inflation?

Some policymakers have argued that we face a “new age of energy inflation” (Schnabel 2022) whereby central banks may be forced to live with a persistently higher level of inflation as a result of both the physical effects of climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy. While the physical effects of climate change such as extreme temperatures may already be impacting inflation, our analysis focuses on the relation between climate policies and inflation—an immediate concern for central bankers, as policies aimed at discouraging high emission activities and promoting clean energy have already been introduced in many advanced economies, and more are likely to come.

In terms of price developments, the outcome of these policies is to raise the price of dirty sectors such as oil and gas, and lower those of green sectors such as renewable energy, relative to those of the rest of the economy. But since these are adjustments in relative prices, not absolute ones, they can in principle take place with any level of overall inflation. In fact, if prices in the rest of the economy fall, and prices for green sectors fall even more, we could even have deflation for the economy as a whole and still achieve the required adjustment in relative prices. In the absence of price rigidities, the central bank can (at least in theory) achieve whatever aggregate inflation rate it chooses without facing any trade-off: the overall price level adjusts rapidly in response to monetary policy without any cost in terms of real activity, while relative prices change swiftly to reflect taxes or subsidies. In such a world, therefore, climate policies would pose no particular problem for inflation-targeting central banks.

Price Rigidities Are the Key

Price rigidities—the fact that prices may not adjust instantaneously but may take a while to do so—make the central bank’s job more complicated. Ignore green energy for a minute and imagine that climate policy consists only of taxes on the dirty sectors. Imagine also that prices for dirty sectors (for example, the oil and gas industry) are flexible, but that those for the rest of the economy are so sticky that they do not move at all (in macro parlance, the Phillips curve for non-dirty goods and services is completely flat). Then the only way to obtain the required adjustment in relative prices—that is, to make dirty goods relatively more expensive—is to have dirty sectors’ prices go up (in other words, inflation).

If prices for the rest of the economy are not completely sticky (the Phillips curve is still quite flat, but not completely so), then the central bank has again some room to maneuver. It can still achieve whatever inflation target it wants, but at a cost: to attain low inflation (or deflation) in the sticky sector to counterbalance the high inflation in the dirty sector, the central bank needs to lower marginal costs and, in particular, wages in the rest of the economy. Unfortunately, this can only be achieved by having output and employment below the levels that the central bank would otherwise target. In other words, price rigidities imply that climate transition policies can create a trade-off for the central bank. Intuitively, the trade-off arises because the central bank needs to “nudge’’ prices in the sticky sector so that the needed adjustment in relative prices occurs with an overall inflation level that is in line with its target. But this nudge is not costless, as it involves cooling down the economy. If the central bank is not willing to do that, it may have to accept temporarily high inflation.

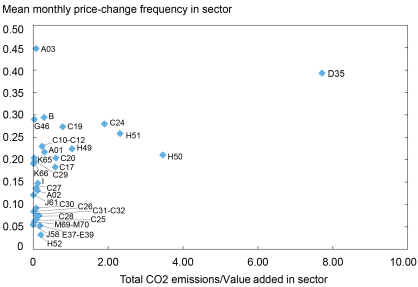

This result still applies even if dirty-sector prices are not completely flexible, as long as they are less sticky than prices in the rest of the economy. The chart below makes the point that empirically this is the case for the U.S. economy. The chart depicts the mean price frequency change in a given sector plotted against its CO2 emissions/value added ratio for thirty sectors in the United States and shows that there is a positive relationship between price flexibility and CO2 emissions. Notice in particular the high frequency of monthly price changes by carbon-intensive sectors such as water and air transport (labeled H50 and H51, respectively) as well as electricity and gas supply (D35). That being said, the positive correlation depicted in the chart remains when omitting sector D35, implying that the relationship is not driven by that sector alone (please see the staff report for the names of the remaining sectors).

Average Price Stickiness Correlates with Emissions per Value Added

Notes: Monthly price frequency change data are sourced from Pasten et al. (2020), who use U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics producer price index (PPI) data to calculate the frequency of price changes at the goods level as the ratio of the number of price changes to the number of sample months. We use the sector average of these measures. The CO2/Value added measure is calculated using 2014 World Input-Output Database (WIOD) data on sector-level value added in combination with emissions information from the WIOD Environmental Accounts. The ratio is expressed in terms of kiloton of CO2 emitted per millions of USD value added produced. H50 (water), H51 (air transport), and D35 (electricity and gas supply), for example, are carbon-intensive sectors. See the source paper for the names of the remaining sectors.

Taxes versus Subsidies

If the presence of this trade-off sounds like bad news for central banks, there may be a silver lining. Climate policies consisting of subsidies to green sectors such as electric vehicles or renewable energy, rather than taxes on dirty sectors, may actually be disinflationary provided that green sector prices are more flexible than those in the rest of the economy. The argument is the same one outlined up to now, but in reverse, because subsidies make goods and services cheaper in relative terms, while taxes make them more expensive. Of course, since green sectors are nascent, we do not have data on their price flexibility, but there are reasons to believe that prices in those sectors are indeed relatively flexible. In this sense, our analysis suggests that if climate policies are more focused on subsidies to the clean energy sector rather than on taxes on polluting activity, they may actually be disinflationary.

Marco Del Negro is an economic research advisor in Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Julian di Giovanni is the head of Climate Risk Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Keshav Dogra is a senior economist and economic research advisor in Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Marco Del Negro, Julian di Giovanni, and Keshav Dogra, “Is the Green Transition Inflationary?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 14, 2023, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2023/02/is-the-green-transition-inflationary/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

You argue that subsidies to clean energy is less inflationary than taxes to dirty energy but what about a combination of the two ? Say, taxes on dirty ones to finance subsidies on green ones. Would it end up to some sort of a zero-sum result ?

Thanks

Luc