In a previous post, we introduced a three-pillar framework for interoperability of payment systems and discussed how technological, legal, and economic factors contribute to achieve interoperability and aid in the “singleness of money”—that payments and exchange are not subject to volatility in the value of the money itself—in the context of legacy systems. In this post, we use the framework to characterize the interoperability of blockchain systems and propose a methodology for evaluating interoperability. We show evidence of limited interoperability and draw insights for the future of payment systems.

Interoperability in Blockchain Systems

- Technical Pillar: The open nature of blockchain systems is sometimes misconstrued as natively enabling interoperability. Each blockchain (for example, Bitcoin or Ethereum) is a separate system that requires services and protocols to be developed in order for data and value to be transferred between systems. Although there are efforts to coordinate on standards (for example, see Cosmos), architectures vary across prominent blockchains and require substantial work.

Demand for exchanging crypto assets resulted in the proliferation of models of interoperability. In the earliest and most popular model, a centralized entity custodies users’ crypto assets and represents ownership on accounts for users on its private system. Trades on the private system are recorded and allow users to withdraw crypto assets according to their holdings. This approach, however, requires users to trust centralized entities to properly manage custodied assets, and is thus susceptible to mismanagement and fraud, as witnessed in the case of Mt. Gox or FTX.

On-chain solutions involve holding pools of assets in their native blockchain systems and issuing representations of those assets in separate non-native systems. A prominent example is wrapped Bitcoin (wBTC), which is the representation of bitcoin on other blockchain systems. These services allow claims associated with bitcoin to be exchanged with tokens issued on a separate system. However, these arrangements still require nontraditional custodial arrangements with varying levels of trust in technical code and lie outside the traditional regulatory perimeter.

Bridges, another on-chain solution of interoperability, allow users to represent and transfer assets belonging in one system through another system using programmable capabilities that require users to trust technical code. For example, a bridge could allow claims of Ethereum-issued tokens, such as USDC, to be represented on different systems. A bridge can send USDC to an escrow wallet in Ethereum and subsequently issue an equivalent representative USDC amount on another blockchain. This approach reduces the need for an active intermediary but exposes users to the bridge developer and to other novel operational risks. Bridges have been shown to be susceptible to technical risks resulting in hacks and stolen funds. In 2023, a hacker stole $320 million worth of Wormhole Ethereum (WeETH) by exploiting a vulnerability in the Wormhole bridge code.

- Legal Pillar: Crypto assets are also characterized by a lower degree of legal interoperability, owing to the uncertainty regarding their treatment within the legal and regulatory environment. Unlike legacy systems, crypto asset systems introduce two headwinds to achieving a high degree of legal certainty.

First, the law underpinning these systems is still under development, so the rights and obligations of the parties can be opaque or uncertain. Interoperation through the models outlined above introduces another layer of uncertainty because mechanisms like nontraditional custodial arrangements and the issuance of representative tokens may signal that the rights of holders have changed—perhaps unexpectedly from a user’s standpoint. For example, the holder may have a contractual right against an intermediary instead of a property right in an underlying asset. Each arrangement would need to be analyzed individually to determine whether that is the case.

Second, all or nearly all of these systems fall outside a regulatory perimeter that would require participants to develop, among other things, sound operational and risk management frameworks. The lack of sound operational and risk management frameworks could increase the likelihood of exceptions arising that undermine the expectations of users. In turn, this failure could compound other risks, including legal risks. These latent risks can be particularly problematic for consumers, who are far less likely than a more sophisticated party to take steps to mitigate or be prepared to take on these risks.

- Economic Pillar: An important design feature of open blockchain systems is accessibility. Anyone is allowed to develop solutions to improve interoperability, and hence economic opportunities drive the development of services that facilitate transfer. Consequently, the provision of services, such as standardization between blockchains on consensus mechanisms (which could substantially improve interoperability), are lagging relative to more profitable functions such as trade.

An uncertain legal and regulatory environment, along with bespoke operational and pseudo-anonymous identity frameworks, can sometimes limit the reliability of such services. Since interoperability is intermediated by entities or protocols with differing degrees of trust requirements, and a clear-cut division of liabilities and enforcement is lacking, solutions requiring some form of custodial layer have led to losses by users without clear recourse. In other words, traditional forces that strengthen incentives of service providers to develop sound operations are absent.

More fundamentally, the lack of a single entity or organization that promotes functioning of cross-chain interoperability contributes to the erosion of “singleness.” For example, segmentation between various cryptocurrency trading venues has prompted a cottage industry of arbitrageurs. Frictions, however, have led to the same crypto assets trading at different prices in different venues, as documented by Makarov and Schoar (2020). This indicates a lack of interoperability across these venues, something that a central authority that organized central clearing could potentially address.

Symptoms of Limited Interoperability

A key tenet of financial economics is the Law of One Price (LOOP). LOOP posits that two assets of identical value should be traded at equal prices. Divergence in prices should draw self-interested traders to buy and sell both claims for profit, and hence, in well-functioning markets, persistence arbitrage opportunities should not exist. Indeed, studies have documented remarkable price efficiency across markets, often pushing toward the physical constraints of speed. By the same token, divergence in prices between two seemingly identical claims implies frictions. An important consideration in the context of blockchain systems is the technical constraints to synchronizing activity across two platforms.

Stablecoins are good candidates for studying interoperability across blockchains because they are nonspeculative by design. Using stablecoins and bridged stablecoins, we examine the price relation between native and bridged USDC and USDT, stablecoins issued by Circle and Tether on multiple blockchains and bridges including Arbitrum, Avalanche, Base, BNB Smart Chain, Cronos, Linea, Polygon, PulseChain, Scroll, and Wormhole. In principle, a bridged representation of an asset (“bridged asset”) represents value that is identical to the original asset.

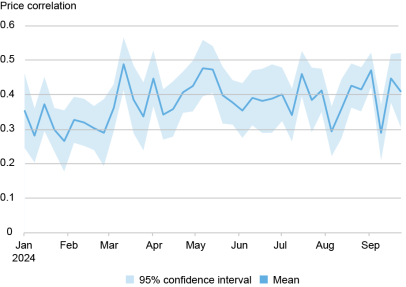

We provide evidence of limited interoperability by showing the divergence of prices of tokens represented on different platforms. The chart below shows the average of the price correlations between native and bridged stablecoins for the first quarter through the third quarter of 2024.

Hourly Prices Between Stablecoins and Their Bridged Versions Consistently Diverge over Time

Notes: The chart shows the price correlation between stablecoins and bridged stablecoins. The sample is the first quarter through the third quarter of 2024.

A higher degree of interoperability in blockchain systems would allow traders to compress any divergence in prices between stablecoins and their bridged representations and push the correlation between the two tokens closer to one. Instead, we find consistently low correlations throughout the sample, with an average correlation of 0.381. Over the sample, the average price correlation also fluctuates, with a high of 0.531 in early May, a low of 0.266 in late August, and an associated standard deviation of 0.057. Correlations also vary significantly across blockchains, as indicated by the wide confidence bounds. Overall, the surprisingly high price variation across blockchains of stablecoins, which are intended to represent $1, points to broad violations in the singleness of money that are not observed for bank deposits. This suggests that limited interoperability contributes to price variation across stablecoins.

Interoperability Lessons for Future Payment Systems

While blockchain systems explore interesting and innovative technological means to facilitate interoperability, connecting multiple blockchain systems to enable crypto assets (or their representations) to move across them, without developing the sound legal and institutional environments, could lead to lower interoperability and revive issues of singleness not present with more traditional forms of money.

Currently, various central banks and consortiums are conducting research and experiments geared toward reimagining the global payments architecture. A significant motivation is the potential to develop the technical capabilities and legal frameworks that facilitate interoperability, building on insights from technological innovations in crypto asset systems, and in particular, the tokenization of assets and related activities. The new payments architecture may take a variety of forms, such as a unified ledger concept or private initiatives such as the Regulated Settlement Network (RSN).

Jon Durfee is a product manager in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s New York Innovation Center.

Michael Junho Lee is a financial research economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joseph Torregrossa is an associate general counsel in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Legal Group.

Sarah Yu Wang is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jon Durfee, Michael Junho Lee, Joseph Torregrossa, and Sarah Yu Wang, “Interoperability of Blockchain Systems and the Future of Payments,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, March 27, 2025, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/03/interoperability-of-blockchain-systems-and-the-future-of-payments/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics