In our previous Liberty Street Economics post, we introduced the decentralized finance (DeFi) intermediation chain and explained how various players have emerged as key intermediaries in the Ethereum ecosystem. In this post, we summarize the empirical results in our new Staff Report that explains how the need for transaction privacy across the DeFi intermediation chain gives rise to intermediaries’ market power.

A Window into Ethereum’s Inner Workings

We collect data from September 2022 (when Ethereum switched to a proof-of-stake consensus algorithm) to September 2024. Our data covers over 5,326,069 blocks added to the Ethereum blockchain. For each block, we track who built it, who proposed it, how much revenue it generated, how this revenue is split between builders and proposers, and which transactions are public or private. This comprehensive dataset enables us to map out the relationships between different players in the Ethereum ecosystem and understand the economic incentives at play.

Our main goal is to understand how access to private transactions affects a block builder’s share of profits. Private transactions often represent valuable arbitrage opportunities that builders want to keep secret until the block is added to the chain. If builders with access to more valuable private transactions can consistently capture a larger share of profits, it suggests that information asymmetry among block builders plays a crucial role in the distribution of profits between intermediaries.

Measuring this effect isn’t straightforward due to the complex dynamics of the Ethereum network. Block builders make several decisions simultaneously: which private and public transactions to include, and how much of the resulting profit to share with proposers. Additionally, other factors such as the overall block revenue and existing relationships between builders and proposers could influence profit sharing.

These interconnected decisions make it challenging to disentangle cause and effect. Does a builder get a larger profit share because they included valuable private transactions, or do they include more private transactions because they know they can negotiate a better profit share?

Crises and Hacks: Our Natural Experiments

To overcome these challenges, we employ a technique known as instrumental variable analysis, which leverages natural experiments. A natural experiment occurs when an external event creates variation in the variables we’re studying, without being directly caused by the outcome we’re investigating. This approach enables us to observe the effects of changes in a system when we don’t have the ability to randomly assign treatments, and is particularly valuable when studying complex, real-world phenomena like financial markets.

In our study, we identify two types of unexpected events that serve as instruments: crypto protocol hacks and major crypto market crises (like the run on Silicon Valley Bank and the FTX bankruptcy). These events affect transaction patterns on the Ethereum network in predictable ways, but crucially, they are not caused by changes in the profit-sharing between builders and proposers.

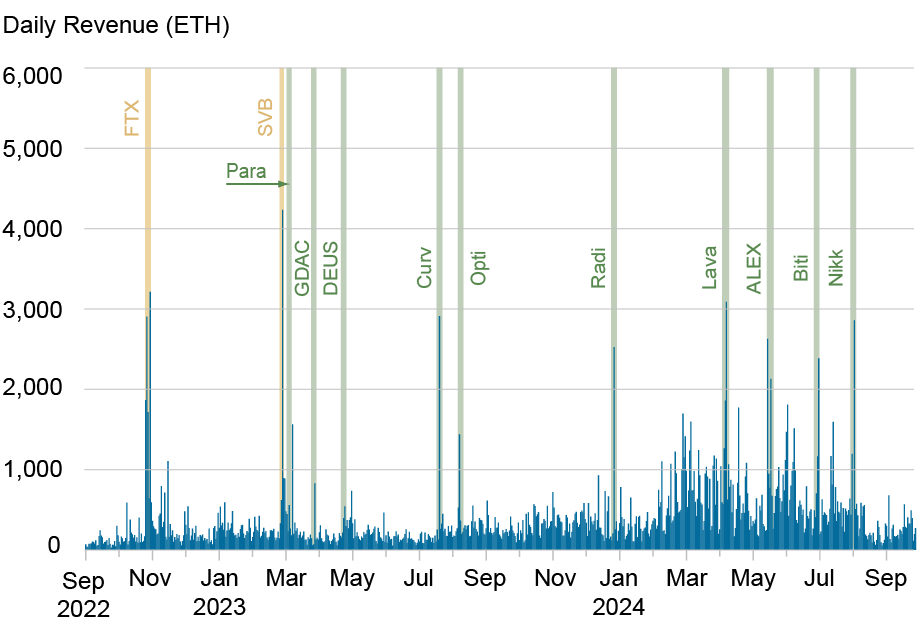

The chart below shows a time series of daily Ethereum revenue, with crypto crises highlighted in yellow, and selected hacks highlighted in green. It illustrates that revenue tends to spike during these unexpected events, leading to a large amount of profit that needs to be split between block builders and proposers.

Aggregate Block Revenue at a Daily Level

Note: This chart shows daily Ethereum revenue after the switch to proof of stake. Days with crypto crises are highlighted in yellow, and days with hacks are highlighted in green

Although both event types tend to raise revenue, our key insight is that they affect the proportion of public and private transactions in the block in different ways. Crises typically increase both public and private transactions as users rush to move their assets or capitalize on market volatility. Hacks, on the other hand, tend to create more opportunities for private, insider-type transactions as those with early knowledge of the hack attempt to protect their assets or exploit the situation. Because hacks tend to have more private information, they will lead to a larger profit share for the builder, who is the only one with access to this information.

The key advantage of this approach is that these events cause changes in transaction patterns that are not caused by the strategic decisions made by builders and proposers regarding profit-sharing. This independence allows us to use these events as instruments to more accurately measure how changes in private transaction value affect builder profits. By analyzing the network’s response to these external shocks, we can draw more reliable conclusions about the causal relationship between access to private transactions and a builder’s ability to capture profits in the DeFi ecosystem, while controlling for other factors that might influence profit-sharing decisions.

The Power of Private Information

Using our instrumental variable approach, we uncover compelling evidence that private information shapes the profit sharing along the DeFi intermediation chain. Our analysis reveals a strong positive relationship between the value of private transactions in a block and the builder’s share of profits. Quantitatively, we estimate that a 1 percent increase in the value of private transactions leads to a 0.57 percent increase in the builder’s share of profits.

This result suggests that block builders derive significant market power from their ability to attract and include valuable private transactions. Builders who consistently access profitable private arbitrage opportunities or other high-value private transactions can leverage this information to capture a larger share of block revenue.

Importantly, when controlling for private transaction value, we find that higher overall block revenue actually decreases the builder’s profit share and increases the proposer’s share. This indicates that public transactions, accessible to all builders, do not contribute to a builder’s market power even when they are highly profitable. Rather, it is the exclusive access to private transactions that provides builders with a competitive edge in negotiations with proposers.

These results paint a picture of a DeFi ecosystem where information asymmetry plays a crucial role in determining economic outcomes. Block builders who can position themselves as gatekeepers of valuable private information can extract higher rents from the system. This dynamic creates incentives for builders to invest in technologies and relationships that give them better access to private transactions, potentially leading to further concentration of market power.

Why DeFi Centralization Matters Beyond Crypto

Our findings reveal a paradox in DeFi: despite its decentralized technology, the ecosystem shows significant centralization tendencies. This matters not just for crypto enthusiasts, but increasingly for the broader financial world.

The key reason is the growing interconnection between DeFi and traditional finance. As large financial institutions enter the DeFi space through vehicles like Ethereum exchange-traded funds (ETFs), they may become participants in the DeFi intermediation chain. These institutions, with their resources and potential access to private information, could further concentrate market power within DeFi.

This development creates a new channel for interaction between decentralized and traditional financial systems. If a few key players dominate critical functions in DeFi due to their information advantage, it could introduce new dynamics similar to those in traditional finance. These key DeFi players could potentially influence the broader financial system, affecting even those who have never directly interacted with crypto or DeFi.

For policymakers and regulators, understanding these dynamics is important for effective oversight that balances innovation with financial stability. For the general public, awareness of these trends provides insight into evolving financial systems that may indirectly impact traditional financial services. As DeFi and traditional finance become more intertwined, the implications of this centralization extend to the broader financial landscape, potentially affecting a wide range of participants in the modern economy.

Pablo Azar is a financial research economist in Money and Payments Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Adrian G. Casillas is a technical associate at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Maryam Farboodi is the Jon D. Gruber Career Development Associate Professor and an associate professor of finance at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

How to cite this post:

Pablo D. Azar, Adrian G. Casillas, and Maryam Farboodi, “The Origins of Market Power in DeFi,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 21, 2025, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/04/the-origins-of-market-power-in-defi/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics