In our last post, we showed that the economic benefits of a college degree still far outweigh the costs for the typical graduate, with a healthy and consistent return of 12 to 13 percent over the past few decades. But there are many circumstances under which college graduates do not earn such a high return. Some colleges are much more expensive than average, and financial aid is not guaranteed no matter which college a student attends. In addition, the potentially high cost of living on campus was not factored into our estimates. Some students also may take five or six years to finish their degrees, which can significantly increase costs. Further, our calculations were based on median wages over a working life, but half of college graduates earn less than the median. Indeed, even when paying average costs, we find that a college degree does not appear to have paid off for at least a quarter of college graduates in recent decades. In this post, we consider when college might not be worth it and explore differences in the return to college by major.

College Is Still Worth It Even with Higher Out-of-Pocket Costs

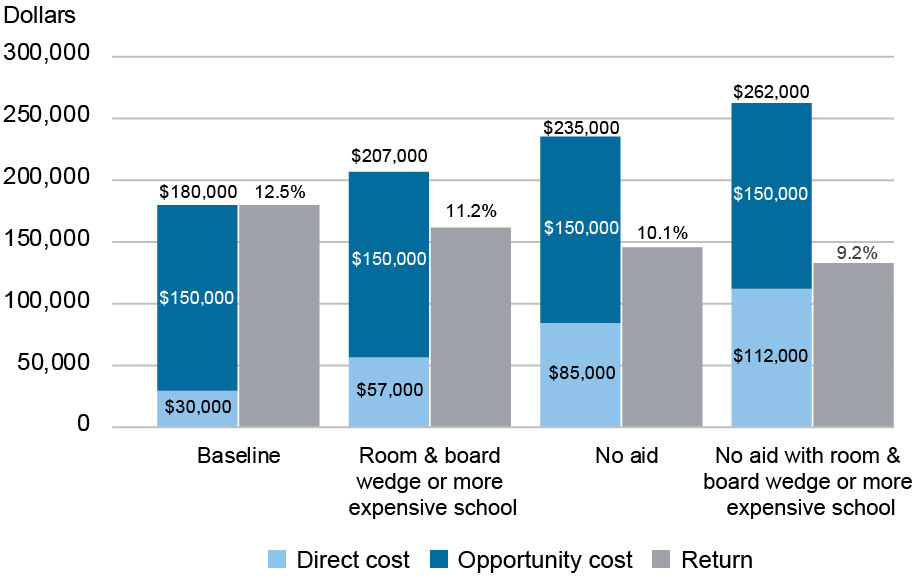

While the average student pays about $30,000 out of pocket for four years of college, there are many circumstances under which someone would pay significantly more. We consider some of these circumstances in the chart below. In each case, we consider differences in direct costs only.

What If You Pay Higher “Out of Pocket” Costs for College?

We first consider the potentially higher cost of living on campus compared to, say, living nearby off campus, by adding half the average on-campus room and board cost, which bumps the total cost from $180,000 to $207,000. Factoring in the extra costs associated with this room and board wedge, the return drops to about 11 percent. This extra cost and the associated return are comparable to attending a more expensive school that is roughly twice the average price. Our next scenario is for a student who does not receive any financial aid and pays the average sticker price of college. Such a student would pay about $85,000 for four years of school (increasing total costs to $235,000) and the return would fall to roughly 10 percent. And, in a third scenario, for a student who doesn’t receive aid and either pays higher costs associated with living on campus or attends a more expensive school, the total cost increases to $262,000 and the return falls to about 9 percent. Under all of these higher direct cost scenarios, the return remains above the threshold for a good investment, though clearly less so than for the typical student paying the average net price.

Taking Longer to Finish Significantly Reduces the Return to College

While most students finish their bachelor’s degrees in four years, many take longer. It turns out that taking an extra year or two to finish school adds considerably to the cost, in large part because of higher opportunity costs. As we have shown before, in addition to the direct cost of paying for an extra one or two years of college out-of-pocket, there is an extra cost in the form of wages that one could have earned with a college degree had one graduated in four years. Also, entering the job market a year or two late damages a worker’s lifetime earnings profile. In addition to giving up one or two years of college-level earnings while in school longer, students miss out on a year or two of experience and the extra push that gives their wages over their working life. Indeed, the total cost of college increases from $180,000 to $272,000 when students graduate in five years and to $364,000 if it takes six years to graduate. The impact of these higher costs on the return to college is shown in the chart below.

Taking Longer to Finish College Costs More Than You Might Think

All in all, we estimate that taking five years to complete college pushes the median rate of return down to about 9 percent and taking six years pushes it down to 7 percent. While these figures suggest college remains a solid investment even if it takes longer to finish, one extra year reduces the return by about a quarter and two extra years pushes it down by more than 40 percent.

College Does Not Pay Off for Everyone

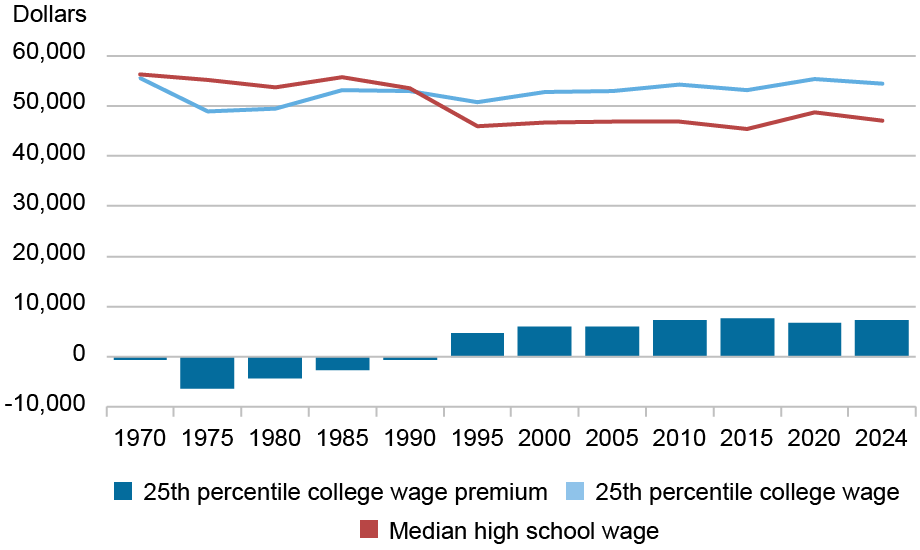

While our baseline estimates focus on the median college graduate, by definition, half of graduates are earning a lower return. Indeed, in the chart below we plot composition-adjusted wages for the 25th percentile of college wage earners compared to the median high school graduate over the past several decades. There is very little difference between the two groups, with an annual college wage premium of well under $10,000. Under our baseline cost scenario, we estimate a 2.6 percent rate of return for the 25th percentile of college graduates in 2024, making college a questionable investment for this group. As we’ve shown before, for at least a quarter of college graduates, college does not appear to pay off.

A Quarter of College Graduates See Little Benefit

Note: Amounts are expressed in 2024 dollars.

Of course, there are many non-economic factors influencing why people choose their job after college, so some in the bottom 25 percent of college wage earners could be making choices based on other considerations. For these people, a payoff calculation may not be particularly relevant. All in all, however, there are some choices that can increase the likelihood of making college worth it.

Your Major Matters

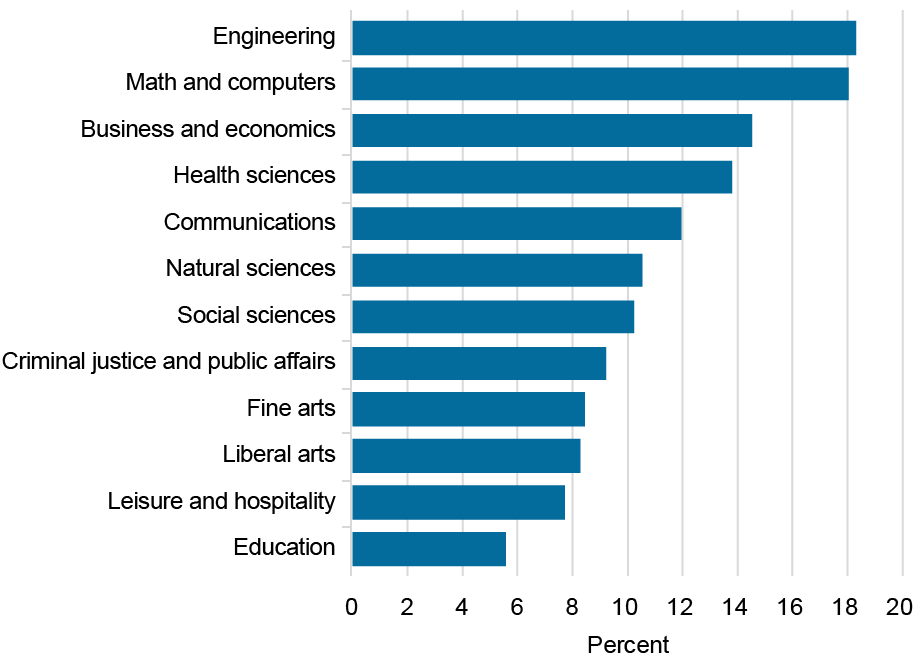

College students can choose their majors, and graduates in some majors tend to earn higher wages than others. Below, we show the return to college for twelve major groupings. For each major, we calculate the median college life-cycle wage premium relative to the median high school graduate and hold the average net price constant across majors.

Median Return to College Differs by Major

Consistent with our earlier research and other recent work, we find that the return varies considerably across majors, though college is a sound investment for the typical student in most majors. Majors providing technical training—that is, quantitative and analytical skills—earn the highest return, including engineering, math and computers, and business and economics. Health sciences majors also earn an above-average return. At the other end of the spectrum, those majoring in fine arts, liberal arts, and leisure and hospitality earn relatively low returns. Returns are especially low for education majors, though it should be noted that annual wages for this group typically reflect teacher salaries for a nine-month school year.

Conclusions

While expensive schools and on-campus living may seem to make college a risky bet, our estimates suggest that even a relatively high-cost college education tends to yield a healthy return for the typical graduate. Taking five or six years to complete a degree also still generally pays off. However, as many as a quarter of college graduates appear to end up in relatively low-paying jobs, and for them, a college degree may not be worth it, at least in terms of the economic payoff. What are some of the things that affect where graduates end up in the earnings distribution? While some of it may come down to choices people make for the jobs they wish to have, one significant consideration is college major, something over which students have direct control. Indeed, majors such as engineering, math and computers, business and economics, and health sciences tend to earn returns well above average.

Jaison R. Abel is head of Microeconomics in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an economic policy advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz, “When College Might Not Be Worth It,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 16, 2025, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/04/when-college-might-not-be-worth-it/

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

I was late making comment in 2014 when I first saw your publications on this topic. I’m glad I came across your current work. The original(2014) paper blandly identified that investing in college had good returns. Replace “college” with “stock market”, “students” with “investors”, etc. and you could have been comparing stocks and bonds. Reality is that college is only a good investment for some people under some circumstances. They do very well for themselves. It is so good for them that they make up for the others who never graduate, major in low-paying subjects or choose low-paying employers. Nvidea makes the average stock price high, but some investors bought bankrupt losers. The college choice is a single-stock investment, not a market investment. I’m glad to see you’re now drilling down into the factors that cause disparity in student outcomes. This is information that would be useful to families considering a college investment.

This is a crucial and timely discussion about the financial realities of higher education. Carefully considering the return on investment is essential for making informed decisions about college.

Thank you for your feedback and interest in our work, Dan. Indeed, based on other research we have done, internships and doing well in your coursework are important factors in getting a good job after college. Exactly how to weigh the prestige of the school you attend against GPA is an interesting question but not something we have researched.

Elated the article addressed many of the key variables that impact the true costs and benefits so often overlooked when making college decisions. Not addressed is (1) the value of cooperative education (robust internships: up to 3, six months each) from colleges like Drexel or Northeastern. (2) the impact of ranking ie GPA but with grade inflation the validity is questionable. This raises the question is it more advantageous to go the more ‘prestigious’ school that accepts you and earn lower grades or vice versa? Perhaps the sweet spot is the college that the student could reasonable expect to finish with a 3.2 and class rank of top 25%.