Banks must extract useful signals of a potential borrower’s quality from a large set of possibly informative characteristics when making lending decisions. A model that speaks to how banks specialize in lending to an industry in order to better extract signals from data can potentially be applied to a number of real-world scenarios. In this post, we apply lessons from such a model to a topic of timely relevance in economics: job market recommendation letters. Institutions looking to hire new economists must evaluate PhD applicants based on limited and often noisy signals of future performance, including letters of recommendation from these applicants’ advisors or co-authors. Using insights from our model, we argue that the value of these letters depends on who reads them.

Specialized Bank Lenders and Borrower Quality

In a recent paper, we (together with our co-authors Zhiguo He and Jing Huang) build a model of the bank-lender relationship, which has the feature that lenders receive signals of borrower quality. A lender that has specialized in the borrower’s business (by lending repeatedly to similar borrowers in the past) can learn about aspects of the borrower’s quality that a more diversified competitor cannot. Armed with such superior information, these lenders can assess loan risks more accurately and bid more aggressively for high-quality borrowers, thereby avoiding the costs of selecting lower-quality borrowers.

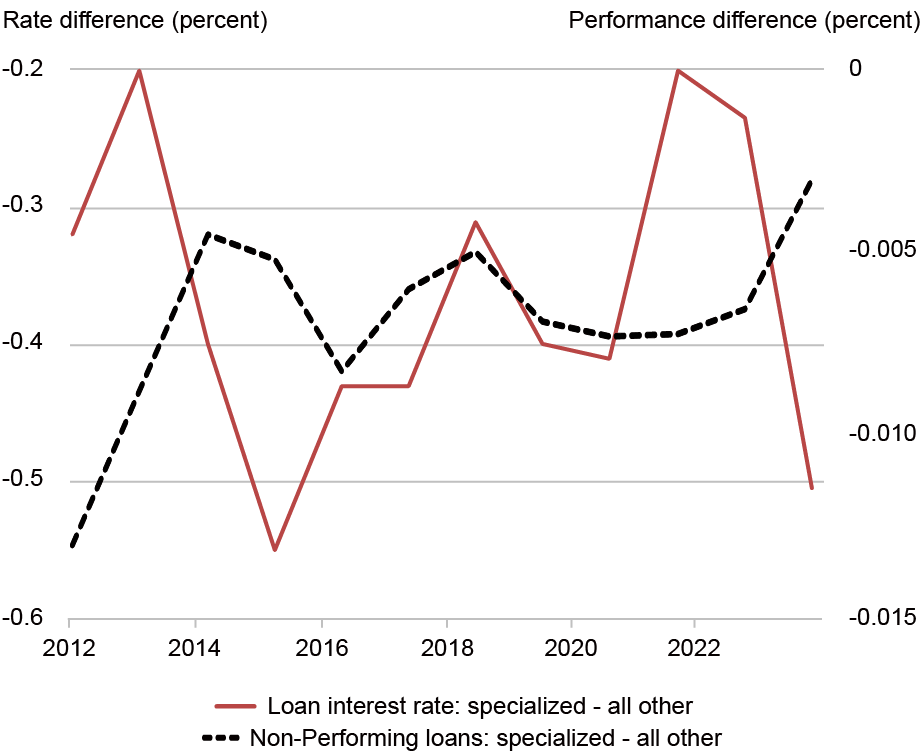

Traditional banking models rely on varying only the precision of a single signal to capture differences in bank screening abilities. These models thus yield strong adverse selection effects (the winner’s curse) and thereby preclude more aggressive rate-setting by the better-informed bank. Our model reconciles traditional views of banking and credit signals with observed reality. In our model, we find that these specialized lenders can offer better terms—lower interest rates—and provide loans that are less likely to default. Thus, specialization enables efficiency-enhancing competition. As can be seen in the chart below, our model’s predictions are well-supported by empirical data. Loans by specialized lenders charge lower rates (for a given risk) and are less likely to default (at a given price) at any point in time. Specialized lenders use their superior information to capture the best borrowers.

Specialized Lending: Lower Defaults and Lower Prices

Notes: We compare the characteristics of loans made by banks that are specialized in an industry with those made by banks that are diversified or specialized in another industry. The red line relates the difference in interest rates paid by borrowers and the black line relates the difference in the likelihood with which a loan becomes non-accruing or defaults. The graph shows residual differences in rates and performance after we account for some borrower characteristics.

Recommendation Letters for the Job Market

Recommendation letters for PhD candidates extol the virtues of the candidate, focusing on their work ethic, past (and expected future) performance, teaching ability, and other skills that the letter writer thinks would make the candidate stand out from their peers. In many cases, the letters are instrumental in determining whether a candidate receives coveted interviews with top-ranked institutions. Notable previous work by colleagues shows that top recommendations are meaningfully correlated with future performance.

The insights from our model apply to some aspects of screening for good candidates in the academic job market. Hiring institutions play the role of lenders and job candidates that of borrowers. Letters of recommendation are akin to signals of borrower credit quality. But just as in our model, what can be learned from those signals depends on the letter reader’s experience and familiarity with the letter writers and with the specific field of study of the applicant. Some candidates receive an unequivocally good signal. For others, the signal strength is less clear, and nuance—which can be parsed by experienced letter readers—plays a role.

Crucially, a committee member who has read hundreds of letters in a field of study and has had repeated interactions with particular writers is akin to a highly specialized lender. Specifically, these members know how to parse subtle cues by better separating the signal from the noise. Conversely, a member unfamiliar with the writer, or with less experience reading letters in general, resembles the non-specialized lender: relying on more generic indicators and potentially missing important nuances.

This helps explain a common observation among hiring committees: letters from well-known advisors often carry more weight, not just because of their prestige, but because experienced readers have learned how to interpret them. It also suggests that recommendation letters may be less portable across fields or subfields of study. A letter written by a preeminent expert in the field of behavioral finance might not be interpreted the same way when read by an industrial organization theorist.

In our lending model, specialized lenders don’t always dominate. They win when they can undercut generalists when bidding for high-quality borrowers—but if the information isn’t precise enough, or if the market is highly competitive, their advantage may be muted. Analogously, in the job market, specialized readers have an edge only when their informational advantage can be brought to bear. This may be the case when they are an important part of the hiring committee and able to make crucial decisions, or when they know how to translate a specific writer’s style into a credible signal that can be communicated to their colleagues on the committee.

Implications for Recruiters and Students

For those wishing to hire top talent—or place top talent well—it makes sense to cultivate deep relationships. Writing letters often (for multiple students each year) may help the recipients/readers of these letters to eventually learn how to parse signal from noise. In that way, a writer who has written letters often may be well placed to send a truly strong signal when it matters most. Similarly, reading letters each year may make someone a better and more effective member of a hiring committee. This may mean it makes sense for institutions to place more seasoned veterans in prominent hiring committee positions. Finally, top students looking to send a strong signal may wish to seek letters by well known and prolific letter writers. Weaker students, on the other hand, may wish to seek out a noisy signal.

Kristian Blickle is a financial research advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Cecelia Parlatore is an associate professor of finance at the NYU Stern School of Business.

How to cite this post:

Kristian S. Blickle and Cecilia Parlatore, “Letters of Recommendation in the PhD Job Market: Lessons from Specialized Banks,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, December 17, 2025, https://doi.org/10.59576/lse.20251217

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics