Over the course of 2025, the average tariff rate on U.S. imports increased from 2.6 to 13 percent. In this blog post, we ask how much of the tariffs were paid by the U.S., using import data through November 2025. We find that nearly 90 percent of the tariffs’ economic burden fell on U.S. firms and consumers.

2025 Tariffs

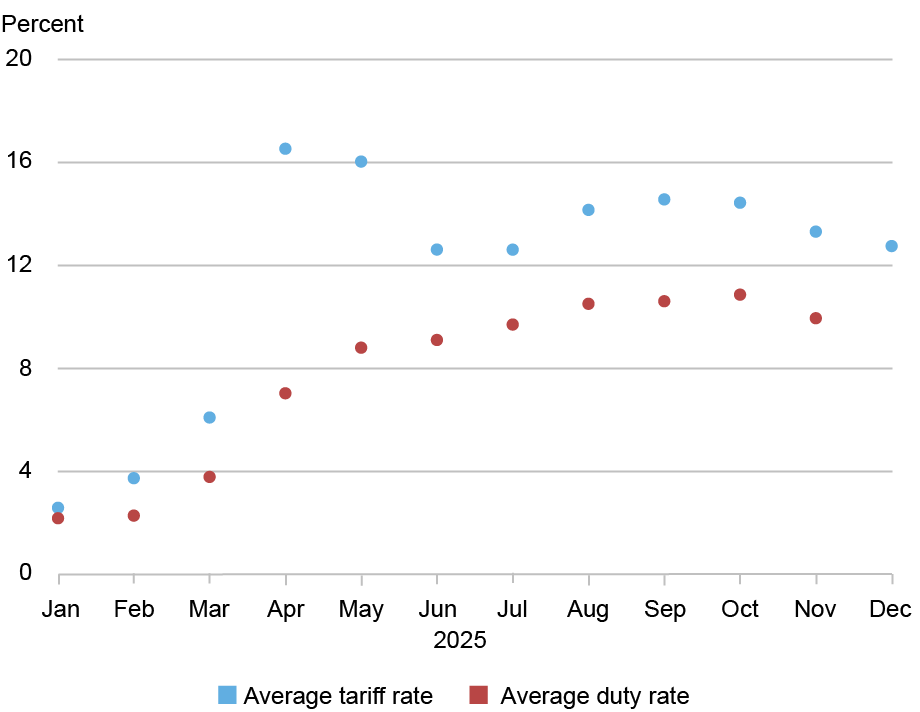

In the chart below, we plot U.S. import tariffs by month in 2025. The blue dots depict the average statutory tariff rate, weighted by 2024 annual import values. The red dots show the average duty rate by month, calculated as total duties collected divided by the value of total imports. The average tariff rate was very low at the beginning of the year, at 2.6 percent. It then spiked in April and May, when tariffs on Chinese goods were raised by 125 percentage points, before being reversed by 115 percentage points in mid-May. By the end of the year, the average tariff rate was 13 percent.

The Average Tariff Rate Has Increased

Notes: The tariff rate is the average statutory tariff rate, weighted by 2024 annual import values. The average duty rate is the total monthly tariff revenue divided by the total value of imports in the month.

The average duty rate is lower than the average tariff rate because of the many exemptions granted. For example, although the U.S. levies a 35 percent tariff on Canadian imports, 83 percent of those imports are exempt from U.S. duties under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). A second reason for the lower average duties is that importers shift away from high-tariffed goods. The difference between the statutory rate and the duty rate peaked in April and May, when importers shifted away from Chinese imports in order to avoid the higher tariffs levied on Chinese goods.

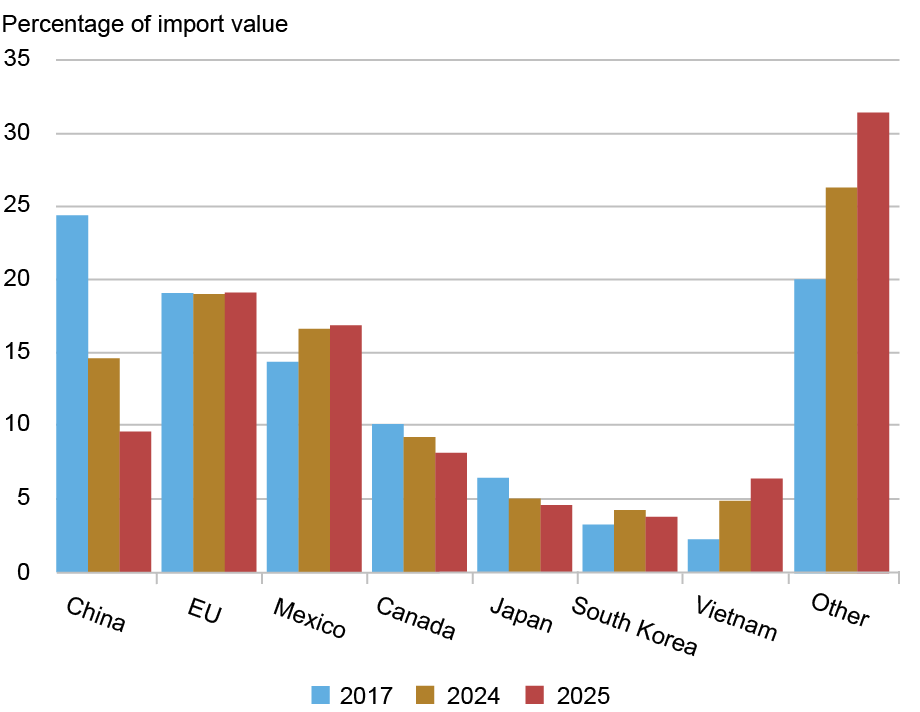

The next chart shows how global supply chains shifted in response to the higher tariffs. We plot import shares by country (or region) for 2017, 2024, and 2025, and countries are ordered by their 2017 import shares. These seven exporters accounted for approximately 80 percent of U.S. imports in 2017, with Chinese goods making up nearly 25 percent of total imports that year. Following a 9-percentage-point increase in tariffs on Chinese goods levied in 2018 and 2019, Chinese imports fell to around 15 percent by 2024. What is striking is that, in the first eleven months of 2025, China’s share of U.S. imports fell by another 5 percentage points, slipping below 10 percent. In contrast, Mexico and Vietnam gained the most market share. China now faces the highest tariffs among the countries and regions shown in the chart.

China’s Share of U.S. Imports Has Fallen Markedly

Notes: The height of each bar represents the value of non-oil imports from that country as a share of total non-oil imports. For 2025 (red bars), the data cover January to November. Countries are ordered by import share in 2017.

Who Bears the Cost of Tariffs?

Tariff incidence is the technical term for how the costs of a tariff are split between foreign exporters and domestic importers. While importers pay the duty, the “economic burden” of the tariff can be shifted onto exporters if they lower their export prices. We illustrate this effect through a simple example: Suppose foreign exporters charge $100 for a good, and the importing country decides to levy a 25 percent tariff on it. If the foreign price remains unchanged at $100, the duty paid is $25, increasing the import price to $125. In this case, the tariff incidence falls entirely on the importer; in other words, there is 100 percent pass-through from tariffs to import prices, and therefore on U.S. consumers and firms.

In contrast, the exporter might lower its price in order to avoid losing market share. If foreign exporters respond to the tariff by lowering their price to $80 (i.e., $100 divided by 1.25), the price paid by importers will remain $100 (with $20 in duties paid to the government). In this case, 100 percent of the tariff incidence falls on foreign exporters, who now receive $20 less for the same good; in other words, there is zero pass-through from the tariff since the import price is unchanged.

Considering an intermediate case, suppose the exporter lowers its price to $96 to absorb some of the cost in response to the 25 percent tariff. The 25 percent tariff is then calculated on the new, lower price, making the tariff-inclusive price the importer pays $120. In this scenario, the lower export price means the exporter pays $4 of the burden, while the higher tariff-inclusive price means the importer pays $20. We define the incidence on the importer as the ratio between the price increase due to the tariff ($120 minus $100) and the total tariff revenues; in this example, the incidence on the importer is 83 percent ($20 divided by $24); the incidence on the exporter (that is, the price decrease they suffer as a ratio of the total revenues from tariffs) is 17 percent ($4 divided by $24).

Because tariff incidence hinges on how tariffs affect export and import prices, we now focus on estimating the impact of tariffs on these prices. We follow the approach used in our previous study, which analyzed the effect of the 2018-2019 tariffs on prices for goods exported to the U.S. In that earlier work, we regressed the twelve-month percentage change in foreign export prices on the twelve-month percentage change in tariffs. We also controlled for average price changes of finely defined products across all countries, and changes in the average price of imports into any country in any month to isolate the differential effects of the tariff. Our past work found that foreign exporters did not lower their prices at all, so the full incidence of the tariffs was borne by the U.S. That is, there was 100 percent pass-through from tariffs into import prices.

We now conduct the same analysis for the 2025 tariffs, covering twelve-month changes from January 2024 through November 2025 (the most recent available data). We report the results in the table below. In this analysis, we also allow the pass-through to change for different months in 2025. Our results show that the bulk of the tariff incidence continues to fall on U.S. firms and consumers. These findings are consistent with two other studies that report high pass-through of tariffs to U.S. import prices.

Tariff Incidence Falls Mostly on U.S. Importers

| Average by 2025 Period | Tariff Incidence on Foreign Exporters (%) (1) | Tariff Incidence on U.S. Importers (%) (2) |

| January-August | 6 | 94 |

| September-October | 8 | 92 |

| November | 14 | 86 |

Notes: The results are estimated on a sample of monthly data at the 10-digit Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS)-country level from 2023m1 to 2025m11, with all variables in twelve-month log changes. The dependent variable is the log change in import prices (proxied by unit values), exclusive of tariffs (i.e., foreign export prices). The independent variable is the twelve-month log change in (1 + tariff rate). We interact this variable with a dummy variable equal to 1 for September/October 2025 and another dummy equal to 1 for November 2025. The regression includes HTS10 product fixed effects and country-date fixed effects.

We highlight two main results. First, 94 percent of the tariff incidence was borne by the U.S. in the first eight months of 2025. This result means that a 10 percent tariff caused only a 0.6 percentage point decline in foreign export prices. Second, the tariff pass-through into import prices has declined in the latter part of the year. That is, a larger share of the tariff incidence was borne by foreign exporters by the end of the year. In November, a 10 percent tariff was associated with a 1.4 percent decline in foreign export prices, suggesting an 86 percent pass-through to U.S. import prices. Given that the average tariff in December was 13 percent (see the first chart), our results imply that U.S. import prices for goods subject to the average tariff increased by 11 percent (13 times 0.86) more than those for goods not subject to tariffs. These higher import prices caused firms to reorganize supply chains, as suggested by the findings presented in the two charts above.

In sum, U.S. firms and consumers continue to bear the bulk of the economic burden of the high tariffs imposed in 2025.

Mary Amiti is head of Labor and Product Markets in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Chris Flanagan is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sebastian Heise is a research economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

David E. Weinstein is an economics professor at Columbia University.

How to cite this post:

Mary Amiti, Chris Flanagan, Sebastian Heise, and David E. Weinstein, “Who Is Paying for the 2025 U.S. Tariffs?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, February 12, 2026, https://doi.org/10.59576/lse.20260212

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics