Neel Krishnan, Antoine Martin, and Asani Sarkar

The summer of 2011 was an unsettling period for financial markets. In the United States, Congress was unable to agree to terms for raising the debt ceiling until August, creating considerable uncertainty over whether the government would be forced to default on its debt. In Europe, the borrowing costs of some peripheral countries increased dramatically, raising questions about the health of some of the largest banks. In this post, we analyze data recently made public by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to see how the U.S. money market mutual fund (MMF) industry reacted to these stresses. We conclude that MMFs appeared to be more concerned with the European debt crisis because they increased their holdings of U.S. Treasuries and other government securities while decreasing their holdings of financial securities issued by European banks over that period.

Money Market Funds before the Debt-Ceiling Crisis

A money market fund is a type of mutual fund that invests in short-term money market instruments. Business institutions typically use money funds to manage a portion of their cash and short-term assets. Retail investors may use them as alternatives to bank deposit accounts. However, unlike deposit accounts, money funds aren’t insured by the government. Even though money funds attempt to maintain a net asset value of $1 per share, investors may still bear losses if the value of the securities in which a fund invested decreases enough to “break the buck.”

For the purpose of this post, we divide all MMFs into two categories: nonprime and prime funds. Nonprime funds include those that buy U.S. Treasury and agency debt and tax-exempt funds investing in state and municipal securities on which the interest is exempt from federal and (often) state income tax. Prime funds are taxable money funds that also invest in securities with taxable interest income, such as certificates of deposit (CDs), commercial paper (CP), and repurchase agreements (repos). Under Rule 2a-7 of the Investment Company Act, the SEC: a) restricts the holdings of prime funds to high-credit-quality short-term securities, b) mandates portfolio diversification that caps fund exposure to individual issuers, and c) prescribes a minimum amount of liquid assets that funds must hold. For that reason, prime funds are also known as 2a-7 funds.

Money market funds attracted record inflows in 2007 and 2008, in part because, as Kacperczyk and Schnabl (2012) observe, some funds invested in riskier assets after the onset of the financial crisis in August 2007 in order to boost returns. This created an incentive for investors to transfer cash from their bank deposit accounts to apparently safe, but higher-returning, MMFs. After the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008, the Reserve Primary Fund was unable to maintain the net asset value of $1 per share due to its exposure to CP issued by Lehman. This event caused a panic, wherein investors moved to withdraw from all money funds. On September 19, 2008, the U.S. Treasury Department insured existing balances on registered 2a-7 money funds, and outflows from money funds slowed considerably.

Money Market Funds during the Debt-Ceiling Crisis

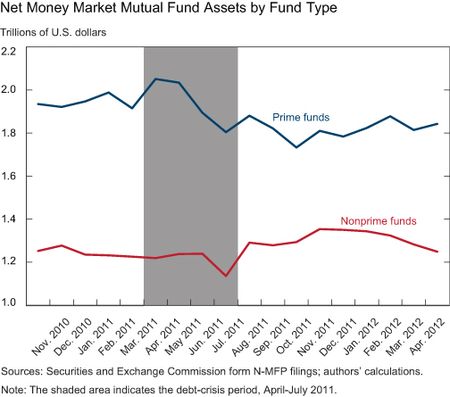

Since 2008, outflows from money funds have continued, as investors no longer perceived money fund investments as low risk and cash-like. Arguing that investors have become more sensitive to differences between money funds, Moody’s revised its money market fund ratings methodology to better capture these risks. How did investors react to the risk that the U.S. Treasury might be unable to pay its debts? The chart below shows net assets of prime and nonprime funds around the debt-ceiling crisis of 2011. The crisis period, indicated by the shaded area, starts from April, when U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner sent the debt-limit letter to Congress, until July, when the crisis was resolved. If the debt-ceiling crisis had increased the perceived risk of U.S. government securities, we might expect to observe outflows from money funds focused on these investments. Instead, the chart shows an increase in net assets (implying greater money flows) into nonprime funds around the debt-ceiling crisis and a decrease in net assets of prime funds.

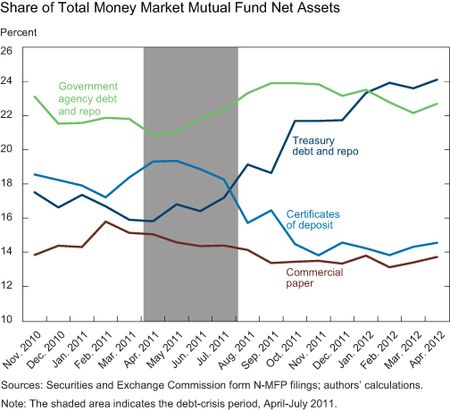

Since prime fund assets are invested in tax-exempt government as well as corporate securities, we provide a clearer picture of fund flows into alternative asset classes by showing in the chart below the share of different securities in net assets of money funds. We find that around the debt-ceiling crisis, there was an increase in the share of net assets in securities related to U.S. Treasuries: agency and government debt, including repos collateralized by these securities. In contrast, there was a decrease in the share of net assets accounted for by corporate securities and, in particular, CDs and CP. Reduced investment in these securities isn’t explained by their lower yields relative to those of Treasury securities of comparable maturity during this period, suggesting that money fund investors considered the securities to have become riskier relative to U.S. government securities.

Money Market Funds and the European Debt Crisis

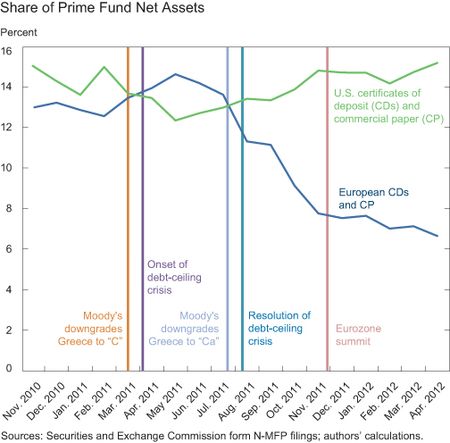

While inflows into U.S. government securities during the U.S. debt-ceiling crisis may seem paradoxical, it’s useful to remember that the European debt crisis had also reached a more severe phase during the same period. For example, there were several downgrades of Greek debt by credit rating agencies between March 2011 and August 2011, as indicated in the chart below. If investors became even more concerned about Europe-related financial risk, then U.S. government securities could’ve been perceived as the safer asset, in a relative sense. Consistent with this idea, we find a decline in holdings of CDs and CP issued by European banks in the portfolios of prime funds starting in May 2011 and continuing to the end of the year. In contrast, while holdings of CDs and CP issued by U.S. banks also declined through May 2011, they recovered thereafter, and particularly following the resolution of the debt-ceiling crisis. In other words, while shifting funds away from riskier corporate securities, money fund investors favored U.S. over European issuers, reflecting their heightened concerns about the European debt crisis.

Maturity of Government Securities

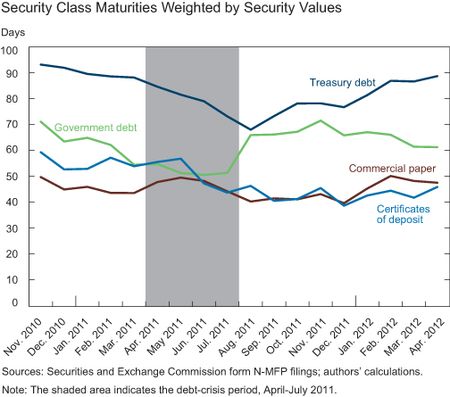

While money funds increased their holdings of securities based on U.S. Treasuries, agency debt, and government securities—in spite of heightened concerns about U.S. government debt—investors perceived that the risk of these securities may nevertheless have increased. For example, the price of credit default swaps written on U.S. Treasuries went up, implying that investors had to pay higher premiums in order to hedge against the default risk of U.S. Treasuries. Such heightened concern for the default risk of U.S. government securities may have been manifested in the decreased maturities of Treasury holdings, so that money funds could exit these investments quickly in case of bad news. The next chart indicates that the average maturity of Treasury holdings of money funds indeed declined during the debt-ceiling crisis and quickly reverted to its precrisis levels once the crisis was resolved.

Conclusion

The dog days of summer 2011 were worrisome for investors, who faced a variety of risks. With a limited number of investment options, money funds had to choose among the least unpleasant of many risky options. Data recently made public by the SEC suggest that money funds considered the European crisis to represent a greater risk than the U.S. debt-ceiling crisis, as they moved away from European assets and increased their investments in U.S. Treasury securities and related assets.

The relatively benign effects of the 2011 U.S. debt-ceiling crisis on U.S. financial markets appear to have been serendipitous, as the U.S. and European debt crises occurred concurrently. Money funds nevertheless reacted to the increased riskiness of Treasuries by dramatically decreasing the maturities of Treasuries held in their portfolios during the debt-ceiling crisis. This behavior suggests that we can’t be sure that the effects of future fiscal crises on financial markets will be similarly benign.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Neel Krishnan is an analyst at TriOnyx Capital.

Antoine Martin is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Don’t forget that during that period August bills sold off dramatically on fears the Treasury would default on specific bills maturing immediately after the money ran out. So the market did react to the fiscal crisis, however at the time most believed congress would resolve the debt ceiling debate immediately after Treasury defaulted on those T-bills.