Gaetano Antinolfi and Todd Keister

The European Central Bank recently lowered from 0.25 percent to zero the interest rate it pays on funds that Eurozone banks hold on deposit with it. On the same day, Denmark’s central bank began charging banks 0.20 percent (that is, paying a negative interest rate) on certain deposits. These events have led commentators to ask what would happen if the Federal Reserve were to reduce the interest rate that banks in the United States earn on funds in their reserve accounts from its current level of 0.25 percent. In particular, some people wonder if lowering this rate would lead banks to hold smaller deposits at the Fed and instead lend out some of these “idle” balances. In this post, we use the structure of the Fed’s balance sheet to illustrate why lowering the interest rate paid on reserve balances to zero would have no meaningful effect on the quantity of balances that banks hold on deposit at the Fed.

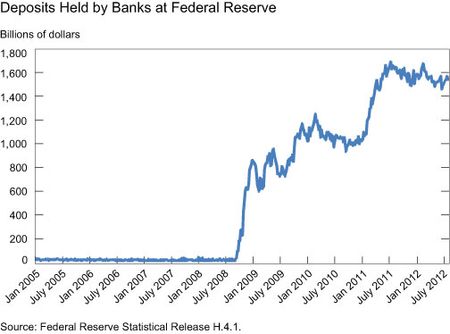

Since 2008, the amount of money banks hold on deposit at the Federal Reserve has increased dramatically, as shown in the chart below. The vast majority of these funds represent excess reserves, that is, funds held above the level needed to meet an institution’s reserve requirement. (See this Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond paper for a more detailed view.) Some observers have called for the Fed to lower the interest rate it pays on excess reserves (often called the IOER rate) as a way of encouraging banks to maintain lower balances.

The View from the Balance Sheet

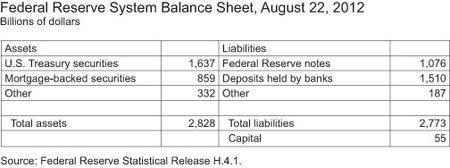

It’s important to keep in mind, however, what determines the total quantity of these balances. One way of understanding the issue is by looking at the Fed’s balance sheet, a simple version of which is presented in the table below.

As the table shows, the balances that banks hold on deposit at the Fed are liabilities of the Federal Reserve System. The other significant liability is currency in the form of Federal Reserve notes. Together, this currency and these deposits make up the monetary base, the most basic measure of the money supply in the economy. The composition of the monetary base between these two elements is determined largely by the amount of currency used by firms and households (both in the United States and abroad) to make transactions and by banks to stock their ATM networks.

What determines the size of the monetary base? As with any other institution’s balance sheet, the Fed’s dictates that its liabilities (plus capital) equal its assets. The Fed’s assets are predominantly Treasury and mortgage-backed securities, most of which have been acquired as part of the large-scale asset purchase programs. In other words, the size of the monetary base is determined by the amount of assets held by the Fed, which is decided by the Federal Open Market Committee as part of its monetary policy.

It’s now becoming clear where our story’s going. Because lowering the interest rate paid on reserves wouldn’t change the quantity of assets held by the Fed, it must not change the total size of the monetary base either. Moreover, lowering this interest rate to zero (or even slightly below zero) is unlikely to induce banks, firms, or households to start holding large quantities of currency. It follows, therefore, that lowering the interest rate paid on excess reserves will not have any meaningful effect on the quantity of balances banks hold on deposit at the Fed.

Language Matters

The language used in the press and elsewhere is often imprecise on this point and a source of potential confusion. Reserve balances that are in excess of requirements are frequently referred to as “idle” cash that banks choose to keep “parked” at the Fed. These comments are sensible at the level of an individual bank, which can clearly choose how much money to keep in its reserve account based on available lending opportunities and other factors. However, the logic above demonstrates that the total quantity of reserve balances doesn’t depend on these individual decisions. How can it be that what’s true for each individual bank is not true for the banking system as a whole?

The resolution to this apparent puzzle is that when one bank decides to hold a lower balance in its reserve account, the funds it sheds necessarily end up in the account of another bank, leaving the total unchanged (see FT Alphaville and this New York Fed Current Issues in Economics and Finance article for more detailed discussions of this point). In the aggregate, therefore, these balances do not represent “idle” funds that the banking system is unwilling to lend. In fact, the total quantity of reserve balances held by banks conveys no information about their lending activities – it simply reflects the Federal Reserve’s decisions on how many assets to acquire.

Other Implications

This logic doesn’t imply that changing the IOER rate would have no effect on banks’ lending decisions, of course. A change in this rate could feed through to changes in other interest rates in the economy and thereby potentially affect the incentives for banks to lend and for firms and households to borrow. Lowering this rate may also lead to disruptions in markets that weren’t designed to operate at very low interest rates (see this earlier post for a discussion). Households and firms could respond to these changes in ways that either increase or decrease the amount of currency in circulation, the level of bank deposits, required reserves, and other variables. These shifts would likely be small, however, and should not obscure the basic point: The quantity of balances banks hold on deposit at the Fed would be essentially unaffected by a change in the IOER rate.

A final note: If the IOER rate were set sufficiently far below zero, banks may choose to store currency rather than hold deposits at the Fed, and households may prefer holding cash if banks impose significant fees on deposits. In this case, the level of reserve balances would decline, but the change would simply reflect a shift in the composition of the monetary base; its total size would remain unchanged for the reasons described above.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Gaetano Antinolfi is a senior economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Todd Keister is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Gregory: You asked why the dramatic increase in reserve balances in our first chart happened at about the same time as the Fed started paying interest on reserves. The Fed’s balance sheet began to expand in September 2008 as a result of the various credit programs that were implemented in response to the crises. This expansion created the large increase in reserve balances. To see this link more explicitly, it might be useful to take a look at the figure on page 7 of this paper: http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/current_issues/ci15-8.pdf, which shows how the increase in reserve balances directly mirrors the size of the credit programs. The policy of paying interest on reserves was adopted in October 2008 to “give the Federal Reserve greater scope to use its lending programs to address conditions in credit markets while also maintaining the federal funds rate close to the target established by the Federal Open Market Committee” (from the press release announcing this decision, http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081006a.htm). In other words, paying interest on reserves gave the Fed a new tool for implementing its target interest rate in an environment with very high levels of reserves. Also note that the stated objective of the policy was to influence the federal funds rate, not the monetary base or other measures of the money supply. Darrell: Our discussion implicitly treats decisions about the size of the Fed’s balance sheet as being independent of the IOER rate. Your comment points to a potential link between these two policy tools. In particular, policymakers may see some substitutability between lowering the IOER rate and making large-scale asset purchases. If so, then a decision to lower the IOER rate may be made in conjunction with a decision to expand the balance sheet by less than would otherwise be done, leaving reserve balances smaller than they otherwise would have been. This is certainly a valid point, although it is difficult to say how closely these decisions might be linked in practice. We simply wanted to make the more narrow point that, as a matter of accounting, lowering the IOER rate while holding the Fed’s balance sheet fixed will not lead to any meaningful change in the quantity of reserve balances. Our apologies for the delayed reply, which reflects the blackout period surrounding last week’s FOMC meeting. Thanks again to everyone for the comments and discussion.

There is a relationship between the rate paid on reserves and quantitative easing (QE) that does indeed imply that lowering the reserve rate should, other things equal, lower the monetary base. Suppose, for simplicity, that the Fed’s QE decisions target a given level of mid term and longer term bond yields. That is, for given macroeconomic conditions, the amount of assets purchased by the Fed over the next year is just enough to get bond yields to some target y. Now, suppose the Fed lowers the rate r of interest paid on reserves. In response, banks are now more anxious to spend reserve deposits to buy assets. Consider the Hypothesis H: The Fed plans to not cooperate by selling assets (securities) to banks, leaving the quantity of reserves unaltered. Then, in order for the market for these securities to clear, their prices must go up (yields go down from y to y'<y). But, the Fed hard targeted a yield of y, so the Fed reduces the amount of quantitative easing that it would otherwise have done. That is, the Fed reduces from its planned level the quantity of reserves that it will create in order to buy securities from banks. Thus, Hypothesis H is contradicted.

I would like to recommend all to read and share this post. Keep up the good work!

The taxpayers subsidize this website? Remunerated excess reserves balances induce dis-intermediation (where the size of the non-banks shrink in size but the size of the CBs remains the same). The payment of interest on excess reserve balances absorbs voluntary savings within the CB system as well as attracts monetary savings from the non-banks & shadow banks. Such a cessation of the circuit income and transactions velocity of funds retards economic growth, increases unemployment, propagates stagflation, & raises the Federal Governments financing costs.

This article completely fails to make a convincing argument against any meaningful relationship between IOER and the amount of excess reserves. Firstly, there is no explanation for the fact that the emergence of sizable excess reserves did not occur until the IOER was first established. A correlation does not imply a cause-effect relationship, but the unbelievably strong correlation begs an explanation. Secondly, Bernanke defended the decision to initiate IOER by saying that it was a means by which the money supply could be managed. That implies that Bernanke completely disagrees with the core message of the article. Thirdly, if IOER has no effect on money supply, then do away with it. The USA appears to have gotten along fine without IOER for many years, so why are the taxpayers now being asked to subsidize banks to the tune of four to five billion dollars a year without benefit?

Thanks, everyone, for the comments and lively discussion. A short reply: We chose to address a somewhat narrow issue: the relationship between the IOER rate and the quantity of reserves. It seems to us that there is still a fair amount of confusion on this point and our aim was to help eliminate some popular misconceptions. In particular, we wanted to show how looking at the Fed’s balance sheet is an especially clear way to see that the total quantity of reserve balances does not provide any information about a bank’s willingness to lend. From your comments, many of you already understood this point, which is great. Several of you wanted us to go further in discussing how changing the IOER rate might affect bank lending. This is a more difficult question, as one has to balance the effect of a (small) decrease in interest rates against the possibility of some market disruptions, as discussed in an earlier post (http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2011/11/why-is-there-a-zero-lower-bound-on-interest-rates.html). We agree this is an important issue, but our focus here was simply on clarifying one thing that lowering IOER would not do: affect the quantity of bank reserves. In response to Ted: The velocity of reserves largely reflects the quantity of interbank lending and is somewhat divorced from other economic activity. In the Fed’s precrisis operating regime, banks had to carefully manage their reserve accounts in order to make sure they met their reserve requirements. This careful management involved large amounts of interbank lending on a daily basis. If a bank was looking like it might be short of reserves on a given day, it would borrow. If it later turned out to have more reserves than expected, it might turn around and lend. This activity implied a very high rate of circulation for reserves. In the current environment, where reserves are no longer scarce, banks generally meet their reserve requirements without much need for interbank lending, which makes the turnover rate for reserves much smaller. But this fall in velocity is not a bad thing – it just says there is less need for short-term interbank lending in the current, high-reserves environment. Lowering the IOER rate would not change this fact, and we would not expect it to have any real impact on the speed at which reserves circulate at banks. Thanks again for all of the comments and discussion.

“This logic doesn’t imply that changing the IOER rate would have no effect on banks’ lending decisions, of course.” Of course. Changing banks’ lending decisions is exactly why folks want the Fed to lower the IOER rate. Currently banks are quite happy to lend $1.5 trillion to the Fed. The IOER rate is the highest safest overnight interest rate they can get. But if the Fed set a negative IOER rate, excess reserves would become a hot potato. As soon as a deposit came in a bank would try to loan it to someone – anyone – other than the Fed. Since total reserves cannot change, banks would do all they could to convert excess reserves into required reserves that pay a positive interest rate. Only if they failed to attract any borrowers would they convert their excess reserves to currency. It is not at all clear that the economic effects of this hot potato game “would likely be small”.

“The resolution to this apparent puzzle is that when one bank decides to hold a lower balance in its reserve account, the funds it sheds necessarily end up in the account of another bank, leaving the total unchanged” Except it gets there by way of a transaction, e.g., the sale of a house by mortgage. Sheesh! “Moreover, lowering this interest rate to zero (or even slightly below zero) is unlikely to induce banks… to start holding large quantities of currency.” Nobody is trying to get banks to hold currency, we are trying to get them to lend more money at these record low interest rates. Yes, it will end up in the account of another bank, but credited to a different customer. “Money is as money does.” The velocity is more important than Why are we paying $4 billion in interest per year on this give-away to banks? It was only supposed to cost $250 million: see Table 1 of http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/72xx/doc7219/senate–re.pdf Why

@Alexander – The point of paying IOER is two fold: 1) It allows the Fed to target a specific Fed Funds rate and size of the monetary base separately. 2) It provides a subsidy to banks helping to build capital and reapir balance sheets. @Ron M – Required reserves are based on the 10% req reserve ratio, which applies to certain types of bank deposits. Excess reserves are any amount held beyond that level, which is based on the Fed’s balance sheet and private sector’s desire to hold currency. Without IOER, banks would have less incentive to hold excess reserves than currently but since currency pays no interest, would probably not change the current breakdown. @Michael – The supply of loans is effectively unlimited at any interest rate, so changing the quantity of lending would require IOER to increase demand for loans. It could do this through slightly lower rates or altering expectations about future rates and asset prices, but those effects are likely small for 0.25%. There are also costs to this policy that probably outweigh those benefits.

“These shifts would likely be small, however, and should not obscure the basic point: The quantity of balances banks hold on deposit at the Fed would be essentially unaffected by a change in the IOER rate.” That is not, in any sense, “the basic point.” In fact, this post completely misses the basic point. Of course the amount of excess reserves held at the Fed at the end of each day isn’t impacted meaningfully by IOR changes. That’s basic accounting. The key question is how many times those reserves circulate each day before ending up back at the Fed. There is every reason to believe that cutting the excessively high IOR could boost base velocity.

I’m with Michael Ashton, as the article seems confused. Ben Bernanke told us back in 2008-09 that the purpose of paying interest on excess reserves was to ‘sterilize’ the increase in the monetary base that the Fed was then creating. It was to protect us from hyper-inflation. Well…that seems to have worked. But, the cost looks to have been excessive; the slowdown in economic activity we’ve suffered since. It’s hardly rigorous logic to say reversing the IOER policy would have no effect.

I. Basically true. Anyhow, some points could be explored for one more complete explanation. a. Central Bank (CB) pays the assets purchases with “reserves” (basically “central bank money”). Negative interest rates on that money will maybe make banks more reluctant in holding reserves, but in the sense that they will probably search for other ways of exchanging the assets in the first place. This could bring more insecurity and be even disruptive to the policy system. b. In this reasoning base money is largely determined by Central Bank (CB), by the amount of assets it holds. The “traditional view” says that there is some deterministic (one way) relation between base money and lending (the money/credit multiplier). Well, as Goodhart (1995) argues, the “credit divisor” is perhaps a best approach to that relation. At least in “normal times”. c. In one bank balance sheet, credit is created “ex-nihilo”, as a double entry. But that doesn’t mean that “funding” isn’t required. In times like this, CB reserves are more likely to accomplish part of that paper, because they can truly be used as mean of payment between banks.

So then what is the point in paying interest on excess reserves?

What is the difference between excess reserves and required reserves? If the Fed paid interest on required reserves but not on excess reserves would banks have an incentive to move their excess reserves to required reserves? What does it take for banks to convert excess reserves to required reserves?

Kind of misses the point. Changing IOER of course doesn’t affect the size of the money base; it would, however, change the quantity of lending done by banks and therefore transfer some of the excess reserves to required reserves. That is, after all, the whole point of increasing the money base (or it used to be) – not to increase the quantity of sterile bank reserves, but to increase the quantity of transactional money, which is the “M” in MV=PQ. Anyone who is still focusing on the money base, assuming the multiplier will remain constant, is missing the point. Put another way, lowering IOER may not affect the base, but it will surely affect the economic impact of the money base. If not, why not crank the rate UP a whole lot, instead, and help out those money funds?