Jason Bram and James A. Orr

Unlike much of the nation, New York City has seen a robust rebound in employment since the recession. In early 2012, employment here reached 3.86 million, the largest number of jobs ever recorded. Yet the city’s unemployment rate has risen in recent months and is now 10 percent—its peak during the recession—and well above the 5 percent rate seen before the downturn. This lack of improvement reflects the fact that the number of employed residents of the city has not rebounded at all from its losses during the 2008-09 downturn. While commuters from outside the city have always been a part of the employment scene, particularly in Manhattan, the recent divergence between the brisk growth in jobs in the city and the lack of growth in the number of employed residents in the city is unprecedented. Moreover, this gap between the two measures continues to widen, raising some questions as to how strong New York City’s recovery actually is. In this post, we explore several alternative explanations for the lack of growth in the employment of city residents in the face of a sharp recovery and expansion of jobs. While there are several potential explanations, the stagnation of resident employment remains largely a puzzle.

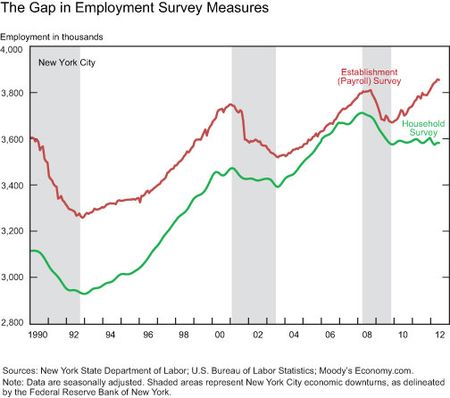

Two estimates of New York City employment are reported each month—the count of the number of jobs (based on a survey of business establishments) and a count of the number of people employed (based on a household survey). Between August 2008 and December 2010 the establishment survey showed that New York City lost 130,000 jobs, or about 4 percent of total city employment, and the household survey showed comparable declines. As of June 2012, however, the establishment survey showed that city employment had rebounded by almost 200,000, reaching an all time high, while the household survey showed no rebound at all. In fact, the unemployment rate, which is calculated from the household survey, has recently crept up—from 9.1 percent in December to 10.0 percent in June.

As shown in the chart above, employment levels, based on these two measures, do not typically match up for a number of reasons. In New York City, establishment-survey levels are typically higher due to substantial net in-bound commuting; in addition, that survey counts a person that works two jobs twice. However, some of this gap is offset by the fact that the household survey defines employment more broadly, in particular, including the self-employed and unpaid family workers. A thorough discussion of these differences, as well as past divergences at the national level, can be found in this study, which also highlights the role of pre-Census population estimates and ensuing Census adjustments in distorting household survey employment trends. However, such distortions do not appear to be a significant factor in New York City’s recent episode. What is so unusual now is not the size of the gap, but rather the divergence from its historical trend—it had gradually been diminishing over time—and the speed with which it has grown.

We look to three possible explanations for why these two employment measures have diverged so sharply in New York City. First, and most obvious, is commuters. Jobs in the city held by people who commute from the rest of the metro area are counted in the establishment survey, but not in the household survey. If most of the new jobs were going to commuters and few to city residents, that would help explain some of this divergence. When comparing the two measures of employment for the remainder of the metro area, however, we find no offsetting gap; that is, we see the same sharp divergence for the broader metro area that we see for New York City. So taken at face value, these numbers suggest that, if city residents are not benefitting from the resurgence of job growth, neither are commuters.

A second possible explanation for the rise of the gap might reflect the treatment of self-employed workers in the two surveys. As the recovery took hold, it could have been the case that large numbers of workers shifted from self-employment (counted in the household survey, but not the establishment survey) to a job in a business (counted in both surveys). This shift would not be reflected in the household survey, because the worker was already counted as employed, but it would show up as a rise in the establishment survey. While current self-employment data are not available for New York City, nationwide data indicate that there has indeed been a shift away from self-employment since 2009. If a similar pattern occurred in New York City—even to a considerably greater degree—it would only explain a fraction of the divergence between the two employment measures.

Finally, multiple jobholders could be a factor. A resident of the city who holds two jobs would be counted as one employed person in the household survey, but counted twice in the establishment survey. An increase in multiple jobholding in the city during this recovery would give rise to a gap. As with the self-employed, we do not have direct evidence of multiple jobholding among New York City residents, nor is there evidence of a rise in multiple jobholding in this recovery at the national level. So unless the city deviates significantly from the nation, this explanation holds little water.

So what are we left with? There seems to be no single over-riding explanation for the gap between the two employment measures. Other indicators of the city’s economy are indicating a healthy recovery, particularly the low office vacancies and rising rents. These developments are consistent with the establishment survey’s estimate of considerable job growth. We will look to future monthly data releases, as well as annual benchmark revisions in early 2013, to help clarify this situation.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jason Bram is a senior economist in the Regional Analysis Function of the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

James A. Orr is an assistant vice president in the Regional Analysis Function of the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thanks for your comments. As to Michael John’s comment, indeed, it is the sharp divergence in the trends of the two measures—the break in the correlation, as you refer to it—not the level of the gap, that is striking. Up until recently, there had been a slow but steady narrowing of the gap, likely reflecting, in large part, an upward trend in reverse commuting and a growing incidence of self-employed workers (such as consultants, contract workers, and independent real estate agents). Both of these trends would tend to boost the household measure, relative to the establishment measure. And it is not only the reversal of this long-standing trend, but also the speed of the divergence, that is unprecedented. However, neither a sharp increase in the working population living in NYC, nor doubling up in households can really explain the gap. This is because even though it is referred to as the “household” survey, it actually does count the total number of people working, not merely the number of households with workers. Aside from the commuting (location) aspect and the issues of multiple jobholders and self-employment, these two surveys are really designed to measure the same concept: the number of jobs held by workers. And with respect to Burton Rothberg, our take is that people who are not working at all would not actually be counted in either of the employment measures for NYC. We cannot tell from the data whether or not there are indeed more flaneurs across the city than in the past. Still, flaneurs could potentially contribute somewhat to a higher unemployment rate but only if they report that they are actively looking for work; otherwise, they would not be counted in the labor force and thus would not be counted as unemployed.

This may seem somewhat off the wall, but I have noticed that there appear to be more young people supported by family money. This is particularly true in hip areas like Williamsburg and the LES. It’s hard to believe that a new generation of flaneurs could contribute much to the unemployment rate, but who knows?

What I find more interesting than the gap is the fact that the correlation between the two measures has broken. The gap was much wider in 1993 but the measures moved with a high correlation up until the very end of the recession. If people are not commuting in from the suburbs then it seems to me the only way to explain such a change is a sudden increase in the population of people available for work living within the city. There has been much talk about migration back to cities in the wake of the great recession. There has also been slow household formation as people ‘double up’ in houses and apartments. Perhaps strong job creation is not enough to keep up with this trend.