Kara Masciangelo* and Jamie McAndrews

One might dispute the biblical assertion that “the poor always ye have with you” (John 12:8, King James Version), but it is indisputable that we will always have the top 1 percent of the income distribution among us. The recent focus on the top 1 percent by the Occupy Wall Street movement has drawn attention to the distribution of income in the United States and the trend toward increased inequality of income in the last three decades (see, for example, this January 2012 speech by the Chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, Alan Krueger).

One might dispute the biblical assertion that “the poor always ye have with you” (John 12:8, King James Version), but it is indisputable that we will always have the top 1 percent of the income distribution among us. The recent focus on the top 1 percent by the Occupy Wall Street movement has drawn attention to the distribution of income in the United States and the trend toward increased inequality of income in the last three decades (see, for example, this January 2012 speech by the Chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, Alan Krueger).

Resentment over the sometimes extravagant lifestyle of the wealthiest 1 percent has been acute at times, perhaps especially in New York, where we find this historical echo of the slogans heard today in Zuccotti Park. Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, in their Pulitzer Prize–winning account of the city’s past, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, remind us of a time in colonial New York when many complained about the lifestyles of the rich.

In the early 1760s, an economic downturn caused a great deal of hardship for most of the residents of New York, including many merchants, recent immigrants, and debtors (many of whom wound up in jail). In the midst of this downturn, the wealthiest merchants, officials, and naval officers did not seem to suffer. One particularly obvious show of distinction and wealth was possession of a carriage. The city’s 85 carriages were owned by only 62 people in New York, whose population was approximately 18,000 in 1760. The modern equivalent (although not as visible, perhaps) might be traveling by private jet rather than by commercial airlines.

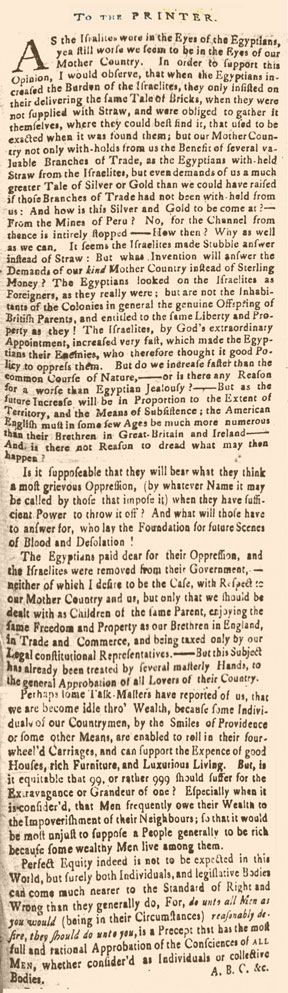

Disapproval of the extreme wealth of the few during an economic downturn was made clear in a 1765 letter to the editor of the New–York Gazette. The letter is primarily about the worsening relations with the “Mother Country,” England. However, the writer also expresses dissatisfaction with affairs in New York in a fashion that presages the “We are the 99 percent” theme of Occupy Wall Street:

Some Individuals of our Countrymen, by the Smiles of Providence or some other Means, are enabled to roll in their four–wheel’d Carriages, and can support the Expence of good Houses, rich Furniture, and Luxurious Living. But, is it equitable that 99, or rather 999 should suffer for the Extravagance or Grandeur of one? Especially when it is consider’d, that Men frequently owe their Wealth to the Impoverishment of their Neighbours.

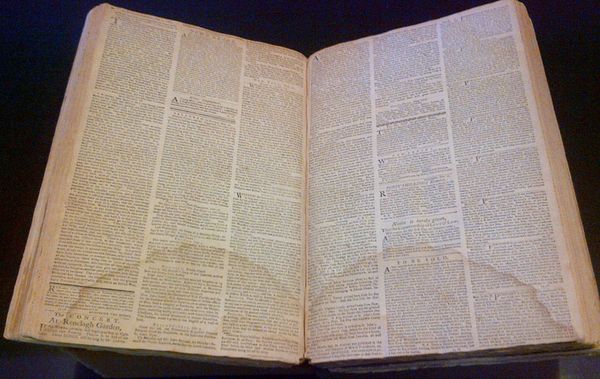

(You can view the edition of the New–York Gazette containing the letter at the bottom of this post, courtesy of the New York Society Library.)

The economic downturn of the early 1760s passed, and the subsequent growth of New York is an amazing story as immigrants flooded the city, industry grew, and technologies progressed. Today, the only carriages remaining in New York are used for a quaint tour of Central Park, not for daily transportation.

There was that revolution, though, that interrupted the life of English colonial New York in 1776 . . .

*Kara Masciangelo is a research librarian in the Research and Statistics Group.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

1765 to 2012!!!!!! Seems like America can never get out of its rut and do something constructive about the inequaities that exists here, Let’s not forget, it took America 100 years to go from the Civil war to Civil Rights, it took 30 years from the Haymarket massacre in 1886 to get an 8 hour work day in 1916, it took another 100 years from the time Teddy Roosevelt introduced the idea of universal health care, to the time it was finally put into law in 2010, and we still don’t have it yet. America really has allot of trouble getting its act together. Any wonder why we are becoming a third world nation? Perhaps we should have a constitutional convention, like Thomas Jefferson suggested. If we can’t change our wealth distribution, and the way we govern, then perhaps it is time for another revoltuionary war, like they had in 1776. Or do we sit on our butts for another 100 years and be satisfied with being poor and indentured to the rich corporate elites?

Thank you for your interest in the post. The discovery of the actual letter was the result of good old-fashioned, purposeful research. After one of us discovered the quote while perusing the pages of Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace’s Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, we determined that including the actual artifact would be essential in illustrating the blog post. The search eventually led us to the reading room of the New York Society Library, where we found a well-preserved run of the New-York Gazette from 1765 in almost perfect condition. We are so grateful that these artifacts remain accessible to researchers. They provided a fascinating window into colonial-era New York and helped us bring the Liberty Street Economics blog post to life. The concerns of the second comment reflect a long-standing recognition in industrial organization, present since the pioneering work of Berle and Means in 1932 (Adolf A. Berle and Gardiner C. Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, [1932] 1968)). A full discussion of the causes of the increased inequality of income in the U.S. goes beyond the scope of our blog post.

If you don’t mind telling, how did you run across this particular letter to the editor? A daily skim of colonial-era newspapers? I really would like to hear the story of the discovery.

While most cite the tax code as the problem behind the growth of income disparity I think that the problem is rooted in the dilution of shareholder rights. The historical reason for stock ownership was to gather dividends that created a stable income stream and this was the primary reward for stock ownership. Share price appreciation was a bonus but not the primary objective of the investor. To be sure speculators sought out share price as the singular goal. Today most executives are not entrepreneurs who founded the companies the administer. They are highly paid professional managers who, through logbbying efforts have erroded shareholder rights and replaced the market for dividends to serve only the speculators. Compensation packages in the multiples of hundreds of times the salaries of workers are now the norm while dividends are vanishing. Shareholders have little-to-no voice in compensation thanks to laws passed in favor of the paid professional management class. Without these laws it is doubtful that shareholders would reward executives at the levels they are paid today. Hence, we have a class of executives answerable to themselves alone. And from that comes the disparity.