Homeownership has historically been an important means for Americans to accumulate wealth—in fact, at more than $15 trillion, housing equity accounts for 16 percent of total U.S. household wealth. Consequently, the U.S. homeownership cycle has triggered large swings in Americans’ net worth over the past twenty-five years. However, the nature of those swings has varied significantly by race and ethnicity, with different demographic groups tracing distinct trajectories through the housing boom, the foreclosure crisis, and the subsequent recovery. Here, we look into the dynamics underlying these divergences and explore some potential explanations.

A quick look at the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances highlights key patterns and disparities in U.S. homeownership. For the median home-owning American household, home equity is their most important asset. This is especially true for Black and Hispanic households: although they have lower rates of homeownership and lower net worth than white households overall, among households that own their primary residence, home equity is a larger part of their net worth than it is for white households that own their primary residence.

Housing wealth has, of course, fluctuated with the housing cycle. Nationally, the homeownership rate hovered around 64.3 percent between 1965 and 1994. But beginning in 1994, homeownership began rising steadily, peaking at 69.2 percent in 2004. The rate then went into decline through the Great Recession and beyond, finally recovering to just over the long-run average in 2016. The increase in homeownership during the boom was driven by a surge of first-time buyers. And the decline in homeownership during the bust was driven primarily by a wave of foreclosures, as many of those first-time owners transitioned back to renting or “doubling up,” reducing the overall number of households.

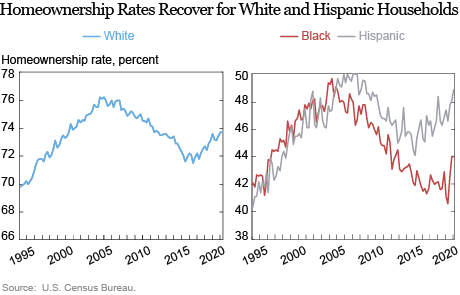

This picture becomes more complex, however, when we break homeownership rates down by race/ethnicity, as shown in the chart below. First, homeownership has historically been much higher among white households, which had a 73.1 percent homeownership rate in the second quarter of 2019, compared to 46.6 percent for Hispanic households and 40.6 percent for Black households. (Note that in this particular dataset, race and ethnicity are defined by that of the household head.) These gaps have been studied extensively by researchers and journalists alike; income and wealth differences, as well as legal institutional racism (especially in the form of redlining), have contributed to these divides.

But even as large gaps persist in homeownership levels, homeownership trends have recently diverged. While white and Hispanic homeownership rates have roughly mirrored the national trend, the Black homeownership rate has experienced a much steeper and longer decline since 2004, falling to a historical low of 40.6 percent in the second quarter of 2019 before edging up in recent quarters.

As a result, the gap between white and Black homeownership has been growing. After holding relatively steady at an already large 27 percent between 1994 and 2007, the gap widened to 29 percent between 2008 and 2017 and has averaged 31 percent since 2018. In contrast, the homeownership gap between Hispanic and white households, though still wide, has contracted slightly over this period.

To explore these gaps more deeply, we turn to the New York Fed’s Consumer Credit Panel (CCP), which is based on Equifax credit report data, to document the experience of individuals as they enter and exit homeownership. We do not observe race or ethnicity in the CCP. Hence, we’ll apply the same framework we employed in our recent post on “Racial Disparities in Student Loan Outcomes,” which uses the zip code of each borrower to derive a proxy for race (based on population estimates from the Census Bureau). In the analysis that follows, white, Black, and Hispanic areas are defined according to the majority race/ethnicity of each zip code’s residents. (Zip codes in which no group makes up the majority of residents are excluded.)

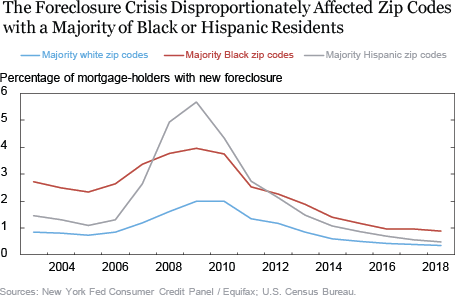

In the chart below, we look at foreclosure rates by area. We see that the foreclosure crisis disproportionately affected zip codes where Black or Hispanic residents form a majority. The very steep increase in the foreclosure rate in Hispanic areas during the crisis reflects, in part, the concentration of majority Hispanic zip codes in such states as California and Florida—places that were more severely affected by the housing boom-bust cycle. It’s also notable that foreclosure rates in majority Black areas have remained higher than those in other areas, although foreclosure rates are low, overall, by historical standards. Thus, residents of majority Black zip codes are more likely to exit homeownership through foreclosure, even now.

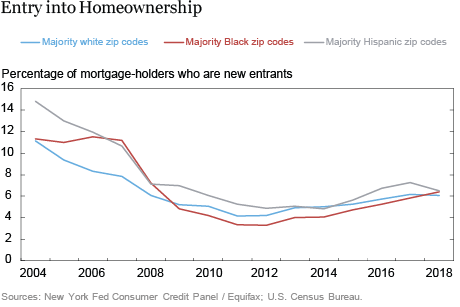

We see a similar trend for entrants to the housing market, proxied by new borrowers’ share of purchase originations. In majority Black areas, the rate of entry into homeownership (new mortgage-holders) was quite high during the boom years, then experienced a sharp decline and remained, until recently, below those in both majority white and majority Hispanic areas.

What’s Going On? Some Potential Explanations

1. Underwriting Standards

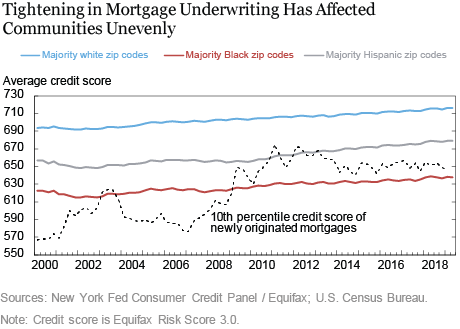

Taking another look at the CCP, we find that the post-recession tightening in underwriting standards has probably had differential impacts on different groups. The dotted black line in the chart below shows the 10th percentile of credit scores of newly originated mortgages, which we could loosely interpret as the minimum credit score needed to obtain a mortgage in a given quarter. Underwriting standards tightened up noticeably in 2006-11, when the minimum score to obtain a mortgage approached 675. This threshold has declined a bit in the past few years, but still hovers around 650: it’s harder for everyone to get a mortgage now than it was in the early 2000s.

The solid lines in the chart below which show the average credit score by community type over time. The average credit score in majority Black areas (red line) is 638, compared to 716 in majority white areas (blue line) and 679 in majority Hispanic areas (gray line). Credit scores do tend to correlate with income (as steady employment and income make it easier to meet debt service burdens), but income doesn’t entirely explain these gaps. The tightening in mortgage lending standards has had the most “bite” in majority Black zip codes, where the average credit score is below the approximate threshold for securing a mortgage.

2. Labor Market Experiences

Another potential explanation stems from differences in labor market outcomes. It’s a completely different world amid the pandemic, but before 2020, unemployment rates were near historic lows for all groups. But periods of unemployment during the Great Recession may have had lingering effects on households’ savings and financial stability. These lingering effects may have been particularly acute for Black workers, who experienced higher unemployment rates during the recession and, relatedly, tend to have longer unemployment spells. The average duration of unemployment was more than two weeks longer for Black workers than for white workers, as of the third quarter of 2019.

Finally, wage growth has followed very different paths for different groups. Average wages for white workers are significantly higher than those for Black and Hispanic workers. But wage trends have differed across groups since the end of 2007, the previous wage peak. Hispanic workers have experienced the strongest growth in real wages, with cumulative real wage growth of 12.6 percent between the fourth quarter of 2007 and the third quarter of 2019. White workers’ real wages have increased by 5.4 percent over this period, while Black workers have only experienced a 3.3 percent pickup in real wages.

3. Student Loans

In our November blog post, we explored the disparities in student loan borrowing by race and ethnicity. We found that individuals who live in areas with higher shares of Black residents are more likely to have a student loan than those in white and Hispanic areas; those borrowers also tend to have higher student loan balances and are twice as likely to default on their loans, with a default rate of 18 percent, compared to rates of 9 percent and 14 percent in white and Hispanic zip codes, respectively. Student loans are associated with lower rates of homeownership among young borrowers, and these different student loan experiences may contribute to the gaps in homeownership between areas.

Homeownership rates have fluctuated for all Americans in the past twenty-five years, with an influx of new homeowners followed by a large‑scale exit from homeownership through the foreclosure crisis. Numerous factors contribute to the fluctuations in homeownership gaps between demographic groups, disparities that have immediate and longer-term implications. As we deal with the economic fallout from the COVID‑19 outbreak in the immediate term, differences in homeownership will likely result in unequal application of economic relief (the CARES Act provides mortgage forbearance to homeowners, among other measures); we will explore such disparities in a forthcoming post. In the long term, gaps in homeownership may have implications for wealth accumulation and inequality.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is an officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is a senior data strategist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Andrew Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Joelle Scally, and Wilbert van der Klaauw. “Inequality in U.S. Homeownership Rates by Race and Ethnicity.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, July 8, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/07/inequality-in-us-homeownership-rates-by-race-and-ethnicity.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics