The term “operational risk” often evokes images of catastrophic events like hurricanes and earthquakes. For financial institutions, however, operational risk has a broader scope, encompassing losses related to fraud, rogue trading, product misrepresentation, computer and system failures, and cyberattacks, among other things. In this blog post, we discuss how operational risk has come into greater focus over the past two decades—to the point that it now accounts for more than a quarter of financial institutions’ regulatory capital.

The Origins of Operational Risk Capital

By the early 1990s, a series of high-profile operational losses had shaken the financial industry, bringing significant attention to the relatively unknown topic of operational risk. In 1995, a trader named Nick Leeson engaged in unauthorized transactions that resulted in losses of more than $1.3 billion, ultimately leading to the collapse of Barings Bank, then the world’s second oldest merchant bank. The incident, along with other rogue trading scandals from that time, helped set the stage for regulatory policy on operational risk in the years to come. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) formally introduced the concept of operational risk in 1998 while working on its new framework (Basel II) and proposed to develop an explicit capital charge for operational risk a year later.

In those early years, the definition of operational risk evolved rapidly. At first, it was commonly defined as a catchall category that captured every type of unquantifiable risk faced by a banking organization—an approach that made operational risk hard to define. In 2004, the BCBS defined operational risk in the main Basel II framework directive as “the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events.” That definition was later clarified to exclude reputational and strategic risks while including legal risk.

Despite refinements, operational risk remained a very broad loss category, covering everything from the physical damage caused by a terrorist attack (September 11, for example) to the financial damage wrought by corporate fraud (as seen in the Enron and WorldCom debacles). The breadth of the definition led the BCBS to further classify operational losses into loss event types and business lines to allow for more homogeneous categories of losses and more accurate estimations of banks’ exposure to operational risk.

By the early 2000s, operational risk had gained more recognition as a material risk for financial institutions and was assessed to be larger than market risk. For internationally active banks, it was estimated to be in the billions of U.S. dollars.

How Big Is Operational Risk Today?

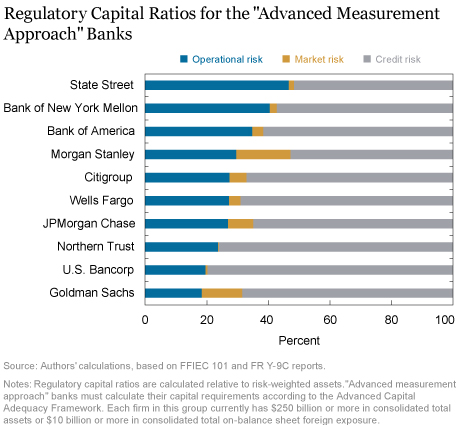

Operational risk is currently a major risk category for U.S. bank holding companies, and it has grown both in dollar terms and relative to other risks in recent years. As of December 2017, operational risk accounted for 28 percent of total regulatory capital, on average, at the group of institutions that are subject to the Advanced Capital Adequacy Framework in determining their capital requirements. (Each firm in this group currently has $250 billion or more in consolidated total assets or $10 billion or more in consolidated total on-balance sheet foreign exposure.) This figure represents a significant amount of capital in comparison to the capital held against market and credit risk (6 percent and 66 percent of total regulatory capital, respectively). Furthermore, in the most recent Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test, the severely adverse scenario projected operational risk losses for the thirty-five participating BHCs of $135 billion, or 23 percent of the $578 billion in aggregate losses projected for these firms over the nine quarters ending in March of 2020.

Exposure to operational risk, however, is not the same across bank holding companies. Studies show that larger and more complex banking organizations are more exposed to operational risk. In a recent research paper, Filippo Curti and Atanas Mihov show that larger banks have higher operational losses per dollar of total assets. Further, this result is largely driven by a specific type of loss: banks’ failure to meet professional obligations to clients or from the design of their products (an event category known as “Clients, Products, and Business Practices”). In another paper, Anna Chernobai, Ali Ozdagli, and Jianlin Wang discuss how banks’ operational risk increases with the complexity of their business—an outcome, they argue, that derives from managerial failure rather than strategic risk taking.

The Future of Operational Risk

Operational risk is intrinsic to financial institutions and poses a significant threat to their financial solvency. Developments in information systems and computing technology have facilitated improvements in the measurement and management of operational risk. However, the same technological advancements that are reshaping today’s business environment are also likely to expose banks to even greater operational risks in the future. It is therefore imperative that banks and supervisors continue to strengthen their approach to managing and mitigating operational risk.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Gara Afonso is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gara Afonso is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Filippo Curti is a financial economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Filippo Curti is a financial economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Atanas Mihov is a financial economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Atanas Mihov is a financial economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

How to cite this blog post:

Gara Afonso, Filippo Curti, and Atanas Mihov, “Coming to Terms with Operational Risk,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics January 7, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/01/coming-to-terms-with-operational-risk.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics