The federal tax cut and the increase in federal spending at the beginning of 2018 substantially increased the government deficit, requiring a jump in the amount of Treasury securities needed to fund the gap. One question is whether the government will have to rely on foreign investors to buy these securities. Data for the first half of 2018 are available and, so far, the country has not had to increase the pace of borrowing from abroad. The current account balance, which measures how much the United States borrows from the rest of the world, has been essentially unchanged. Instead, the tax cut has boosted private saving, allowing the United States to finance the higher federal government deficit without increasing the amount borrowed from foreign investors.

What Determines a Country’s Borrowing?

As an accounting matter, a country’s income is allocated to either consumption or saving while spending goes to either consumption or investment to replace or expand the capital stock. These two identities mean that a nation’s saving equals its investment spending when income equals spending. Opening up to the rest of the world through trade allows a country to have its income exceed its spending when its exports exceed its imports and this difference exactly equals the difference between gross saving and investment spending. Indeed, the gaps between spending and income, between saving and investment spending, and between exports and imports all equal a nation’s lending to (or borrowing from) the rest of the world.

These identities are useful for backing out saving data that are hard to calculate directly. That is, a country’s total gross saving can be calculated indirectly as the sum of investment spending and the current account balance. This relationship can be seen by rearranging the identity presented in the previous paragraph: the current account balance (the broadest measure of the trade balance) equals the gap between saving and investment spending—that is, CA = S – I. Saving can thus be backed out using current account and investment spending data.

Borrowing Less from Abroad Since the Great Recession

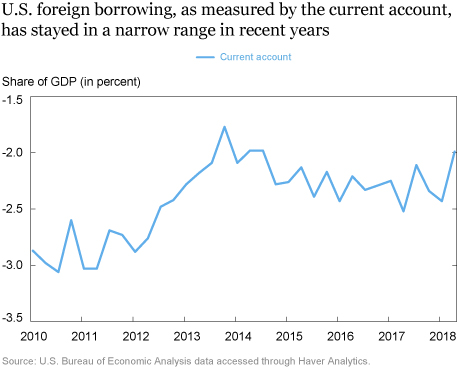

The United States borrows from the rest of the world when its gross physical investment spending exceeds it gross saving. The nation was borrowing amounts equal to around 5.0 percent of GDP in the run-up to the global financial crisis. In recent years, however, borrowing from abroad has been much lower, averaging less than 2.5 percent of GDP a year, as seen in the chart below. The most recent observation is for the second quarter of 2018, when borrowing fell to 2.0 percent of GDP. (Partial data suggest borrowing in the third quarter was near the pace set in the first quarter of the year.)

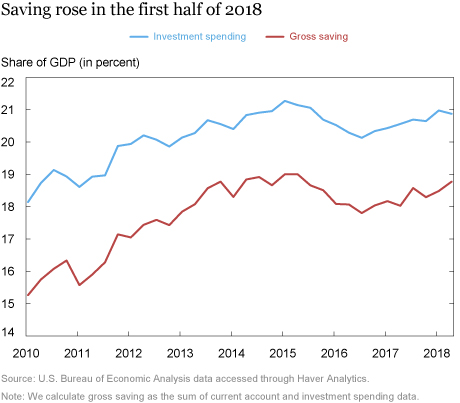

The chart below of gross investment spending and saving shows the downshift in borrowing relative to pre-recession levels is due to saving as a share of GDP recovering faster than investment spending. More recently, saving has been fairly stable through the second quarter of 2018. Note that total saving is the sum of personal, business, and government saving, and, in each case, saving is calculated as the difference between current income and current expenditures, excluding investment spending and depreciation. For example, government saving is the difference between current receipts and current expenditures on consumption, transfers, and interest payments. (The fiscal deficit is larger than government dissaving because it includes investment spending.)

The next chart shows that the key driver of higher U.S. saving after the Great Recession was the improvement in federal government saving. Taxes were cut and temporary spending increases reduced government saving during the downturn, but spending was subsequently cut back, a number of tax cuts were eliminated, and a growing economy increased tax revenues. Government saving thus became substantially less negative and helped raise total U.S. saving. However, a turnaround caused by the 2018 fiscal actions on federal government saving is evident in the latest data, with dissaving deteriorating from 2.0 percent of GDP in the first half of 2017 to 3.4 percent of GDP in the first half of 2018. In dollars, government saving dropped by around $300 billion (annualized rate) from the year-ago level.

Private Saving Offsetting the Drop in Government Saving

In our earlier chart calculating gross saving as the sum of the current account and investment spending, saving is unchanged in the first half of 2018 because the large drop in federal government saving was offset by an increase in private saving. National Accounts data include estimates of government, business, and personal saving, with the caveat that the sum of these three components is consistently less than the total saving calculation done above. (Note also that business and personal saving are not nearly as well measured as government saving, and that the three components together currently have total saving about 0.5 percentage point higher than total saving calculated using current account and investment spending in 2017.) Still, the business saving data are instructive in pointing to this component of private saving as the reason total saving has not dropped as a share of GDP with the change in government saving. Specifically, business saving in the first half of 2018 was up $370 billion (annual rate) over the year-ago level, while household saving was up $105 billion over the period.

These offsetting changes in saving have left total U.S. saving largely unaffected, meaning that the higher federal government deficit did not require an increase in foreign borrowing. Of course, these are early days and it will be interesting to see how the increase in business saving will play out. For example, the increase in that saving component may diminish over time, perhaps because firms pass on some of their profit boost from lower taxes to their customers via a drop in markups. Firms could also use their higher after-tax income for salary increases in the current tight labor market. A third possibility is for firms use the jump in saving to increase their capital stock through higher investment spending. Indeed, this perspective suggests that a deterioration in the trade balance is a sign that firms are passing on the gains from the tax cut to their employees and consumers.

Finally, the additional downward pressure on government saving going forward will be from higher spending. It may turn out that future drops in government saving from higher spending translate more directly into higher borrowing from abroad.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Linda Wang is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Linda Wang is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Thomas Klitgaard and Linda Wang, “Is the United States Relying on Foreign Investors to Fund Its Larger Budget Deficit?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), November 28, 2018, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/11/is-the-united-states-relying-on-foreign-investors-to-fund-its-larger-budget-deficit.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

I follow Bill Mitchell and as a result of that I believe that Treasuries do not fund Congressional spending. They are irrelevant to Congressional spending, in fact. Anyway, this particular blog, in my humble opinion, misleads the reader and reinforces the veil that somehow the federal fiscal statement is just like our family budget. The federal government’s fiscal statement of expenditures and receipts cannot break down or get sick. It is simply a record of dollars spent into existence and dollars taxed out of existence. It is impossible for a government to borrow its own currency. When the central bank sells Treasuries in exchange for reserves, it is merely swapping one non-government sector asset for another. Reserves get converted into bonds of equivalent value. Bond issuance is a portfolio reshuffle for the non-government sector. It does not net add financial wealth to the non-government sector.

In reply to Jose Oyola: Data on net foreign purchases of U.S. Treasury securities are published in table 7 of the International Transactions data release from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data through the second quarter show that the pace of these purchases is down in the first half of 2018 relative to the first half of 2017. Foreign investors will continue to buy these securities and may well pick up the rate of purchases going forward. The point of the blog was that the substantial jump in the fiscal deficit has so far not caused the U.S. economy, as a whole, to borrow from foreign investors at a faster pace than it was before the tax cut. https://www.bea.gov/data/intl-trade-investment/international-transactions

What in the world is “Government Savings”? The Government literally owns the printing press for US Dollars. The government can spend or not spend. It doesn’t need an investment or savings account. How are they “saving” money?

How do you reconcile the national stats in this article with the UST data on foreign ownership disclosed in https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ap_4_borrowing-fy2019.pdf