Nonfinancial corporations focus on the growth in earnings per share (EPS) to benchmark their performance. Banks used to follow a similar practice, but starting in the late 1970s they began to emphasize return on equity (ROE) instead. In this blog post, we outline findings from our recent staff report, which argues that banks had an incentive to make this change when their charter values eroded owing to increased competition, and the incentive to change was magnified by risk-insensitive deposit insurance.

Did Banks Always Use Return on Equity to Measure Performance?

Traditionally, nonfinancial corporations emphasized performance targets linked to their EPS. For example, in its 1940 annual report, Black and Decker noted that “the net earnings for the year available for dividends amounted to $1,064,095.29 or earnings of approximately $2.82 per share, as compared with net earnings of $595,851.34 or $1.60 per share for the previous year.” As of 2000, the company was still using remarkably similar language when describing its financial performance.

Banks also appear to have favored metrics linked to EPS up until the late 1970s, but since then their preference has shifted toward ROE. For example, the Bank of Boston noted in its 1979 report that “The Corporation earned its highest return on your invested capital in more than a decade. Our return on stockholders’ equity, which dipped as low as 8.4 percent for 1976, climbed to a healthy 13.7 percent for 1979.” Since then, the Bank of Boston has emphasized ROE every year.

In our staff report, we document that stock market investors recognize this difference between banks and nonfinancial firms. Using a constant sample of U.S. banks and nonfinancial corporations since the early 1970s, we show that the market-to-book values of banks’ stocks react more to ROE announcements than EPS announcements while the reverse occurs for nonfinancial firms. In addition, we find that banks’ market-to-book equity became relatively insensitive to EPS only after the 1980s. Thus, firms’ choice of performance metrics matters to stock investors.

Why Do Banks Use Return on Equity to Measure Performance?

We explain banks’ preference for ROE using a theoretical model of a bank that maximizes its shareholders’ value in excess of the shareholders’ contributed capital. The model has two key elements: First, the bank’s deposits are insured by the government; second, the bank has “charter” or “franchise” value that derives from its ability to pay interest on insured deposits that is below a competitive risk-free rate. Using the model, we show that when banks respond to greater competition and have fixed-rate deposit insurance, then ROE makes banks appear more financially healthy than EPS growth does.

When more competition erodes banks’ charter values, they rationally reduce the amount of their equity capital relative to deposits, and the decline is greater when banks are subject to fixed-rate, rather than fair-value, deposit insurance. While lower charter value reduces their net interest margin and EPS growth, the decrease in equity capital causes a further worsening of EPS growth.

What happens to the ROE measure when a bank reduces its initial capital in response to greater competition? Surprisingly, the effect is a rise in ROE growth that can easily offset the mechanical decline from a lower net interest margin. Moreover, banks reduce capital more when deposit insurance is risk-insensitive, which makes ROE look even better than it would if deposit insurance were fairly priced. In summary, responding to greater competition by lowering capital makes a bank’s ROE measure look better and its EPS growth look worse.

Can the Model Explain Banks’ Recent Preference for the Return on Equity Measure?

Having fixed-rate deposit insurance increases banks’ preference for holding lower levels of equity capital and, in turn, for targeting ROE. Historically, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) insurance premiums have been assessed without regard to bank risk. It was only in 1991 that the FDIC changed this flat-rate assessment system to one based on each bank’s level of risk. However, effective insurance premiums in the following years remained only mildly linked to bank risk.

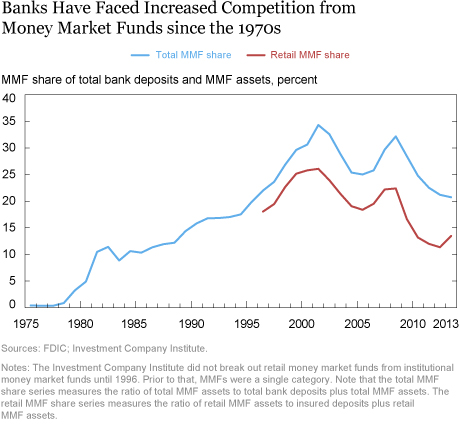

Increased competition that reduces charter values also gives banks a preference for holding lower levels of equity capital and, thus, using ROE as a performance metric. Starting in the late 1970s, U.S. banks were exposed to increasing competition from nonbank financial institutions. In particular, money market funds competed directly for bank deposits, as shown in the chart below. Competition in the banking sector further intensified in the 1980s following states’ decisions to lift restrictions on branching within their borders and to permit out-of-state institutions to acquire their banks.

Implications of Post-Crisis Bank Regulations for Banks’ Use of ROE Measure

Our model predicts that banks would be especially resistant to any post-financial crisis regulation, such as Basel III, that requires them to increase their equity capital. After Basel III, a typical bank’s performance is worse on an ROE basis than on an EPS basis, and if minimum capital standards continue to rise, we could see banks de-emphasize ROE in favor of EPS, reversing the recent historical trend.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

George Pennacchi is a professor of finance at the University of Illinois.

João A.C. Santos is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

João A.C. Santos is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

George Pennacchi and João A.C. Santos, “Why Do Banks Target ROE?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), October 9, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/10/why-do-banks-target-roe.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics