Many market participants believe that large financial institutions enjoy an implicit guarantee that the government will step in to rescue them from potential failure. These “Too Big to Fail” (TBTF) issues became particularly salient during the 2008 crisis. From the government’s perspective, rescuing these financial institutions can be important to avoid harm to the financial system. The bailouts also artificially lower the risk borne by investors and the financing costs of big banks. The Dodd-Frank Act attempts to remove the incentive for governments to bail out banks in the first place by mandating that each large bank file a “living will” that details its strategy for a rapid and orderly resolution in the event of material distress or failure without disrupting the broader economy. In our recent New York Fed staff report, we look at whether living wills are effective at reducing the cost of implicit TBTF bailout subsidies.

What Is a Living Will?

Section 165(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act requires that banks with over $50 billion in total consolidated assets submit annual resolution plans, although a recent amendment increases the asset threshold to $250 billion. The requirement also extends to nonbank financial companies designated as systemically important by the Financial Stability Oversight Council. Such plans, commonly known as living wills, must describe substantive, detailed strategies to achieve a resolution when experiencing financial distress or failure.

Under the Dodd-Frank Act, the Federal Reserve Board and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation can jointly determine that a living will is not credible or would not facilitate an orderly resolution under the ordinary U.S. resolution regime. In the latter case, the agencies can issue a notice of deficiency detailing the perceived shortcomings in the plan and actions the firm must take to address them within a specified time frame or risk stiff penalties, such as higher capital or liquidity requirements, or forced changes in organizational structure. For example, the agencies jointly determined that there were deficiencies in Wells Fargo’s plan in December 2016, and consequently prohibited the bank from establishing international bank entities or acquiring nonbank subsidiaries.

Regardless of whether the plans pass regulatory scrutiny, banks must also disclose a substantial part of their living wills to the public. Hence, being subject to the living will requirement is arguably economically meaningful, both de jure and de facto.

Do Living Wills Result in Higher Cost of Capital for Banks?

If living wills reduce the probability that large banks will be bailed out, then investors would no longer be willing to offer artificially low funding costs. Thus, the cost of capital of banks subject to living wills should increase. Since only the largest banks qualify for the living will mandate, we cannot compare banks subject to living will regulations with identical banks that are not subject to such regulations. Therefore, we opt for an empirical approach that tries to create a matching bank by looking at a number of firm characteristics (in addition to size), thus assigning to each treated firm its own synthetic control. Hence, if the regulation actually has an impact on the cost of capital then, prior to its implementation, we should expect similar costs of capital for affected banks and their synthetic pairs but, following its implementation, a relatively higher cost for banks subject to the policy.

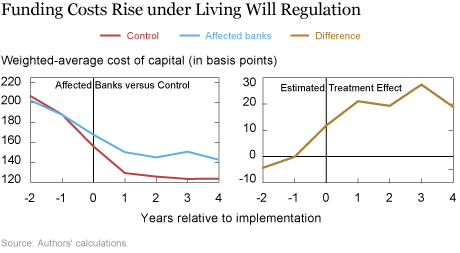

We find that living wills indeed increase the cost of capital of affected banks, relative to the comparison group, consistent with reduced investor expectations of a bailout. The chart below plots this increase, which we find economically large and persistent. The y-axis measures the cost of capital in percentage points, and the x-axis indexes the years from the living wills’ implementation (0 is the first year active). The left panel shows the cost of capital for banks subject to the regulation and their corresponding control group. The right panel simply tracks the difference between the two lines in the left panel, thus showing an overall cost of capital increase of about 22 basis points on average for each quarter after the treatment. This sum is economically important, as it is about 10 percent of the average funding costs for these banks.

To provide an estimate of the dollar-amount increase in banks’ cost of capital, we multiply the estimated basis-points increase for each bank by the bank’s total capital size. Aggregating across all banks subject to the regulation, we find that living wills resulted in higher cost of capital of about $42 billion annually. Citibank alone saw an increase in cost of capital expenses of $14 billion. While the effects are less pronounced for the smaller institutions focused on commercial banking, they remain large for those focused on other financial services.

It is important to note that living will regulation should also make banks safer, and lead to a decrease in the cost of capital. Since we only observe the net effect on the cost of capital, the increase in cost of capital from reducing expectations of a bailout is most likely larger than what we estimate, Hence, our evidence of an increase in the cost of capital is likely a lower bound of the overall impact of living wills in reducing expected bailouts.

A Heavier Cost on More Interconnected Banks?

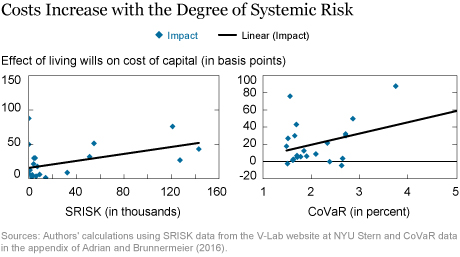

Is there a bigger effect of living wills on more systemically important banks? To explore this question, we plot two measures of systemic risk (SRISK and CoVaR) prior to the living wills announcement in 2011 against our estimated effect of living wills on changes in the cost of capital. In the chart below, we see the cost of capital increases more for banks with greater systemic risk in 2011. In other words, the increase in capital cost from living wills is directly related to the banks’ bailout likelihood in 2011.

What Do We Learn from Living Wills?

Living wills and the associated regulations were intended to establish the conditions under which an ex-post policy of not bailing out banks could be credibly implemented. Our study suggests that markets have anticipated an economically significant reduction in the cost-of-capital subsidy as a result of the living wills.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Nicola Cetorelli is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Nicola Cetorelli is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

James Traina is a University of Chicago Ph.D. candidate in financial economics, in a program jointly administered by the Department of Economics and the Booth School of Business. He is also a former senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Nicola Cetorelli and James Traina, “Resolving ‘Too Big to Fail,’” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), October 2, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/10/resolving-too-big-to-fail.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics