During the global financial crisis of 2007-08, collateral markets became illiquid, making it difficult for dealers to obtain short-term funding to finance their positions. As lender of last resort, the Federal Reserve responded with various programs to promote liquidity in these markets, including the Primary Dealer Credit Facility and the Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF). In this post, we describe an additional and rarely discussed liquidity facility introduced by the Fed during the crisis: the TSLF Options Program (TOP). The TOP was unique among crisis-period liquidity facilities in its provision of options. A follow-up post will analyze dealer participation in the TOP.

What Did the TOP Do?

The TOP acted as an extension of the TSLF, which was introduced in March 2008. The TSLF was created to aid the functioning of secured funding markets by offering twenty-eight-day loans to primary dealers. These loans took the form of liquid Treasury securities, which were collateralized with less liquid securities. The dealers could use the Treasury securities as collateral to obtain funding readily in the private collateral markets.

The TOP was announced in July 2008 to further mitigate illiquidity in collateral markets. It was specifically intended to offer loans over periods of heightened collateral pressures, such as quarter-end dates. Moreover, the TOP was unique among the Fed’s crisis liquidity facilities in that it involved the sale of nontransferrable options—primary dealers were awarded options that provided them the right, but not the obligation, to borrow Treasury collateral on a specified future date. Borrowers that chose to exercise their options would pay a fee and pledge eligible collateral, as with regular TSLF loans. Also as in the TSLF, a broad range of highly rated securities were accepted as eligible collateral.

How Did the TOP Work?

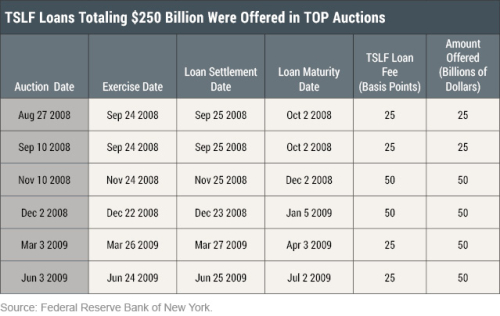

Six TOP auctions were held over the life of the program, as shown in the table below. The auctions covered five different month-end periods between September 2008 and June 2009 (there were two auctions for loans covering the end of September 2008). The option exercise date was two to four weeks after the auction. Loans were settled one day after exercise and typically matured seven days later, or thirteen days later for loans covering the end of December 2008. For each exercise date, a total of $50 billion in TSLF loans was offered.

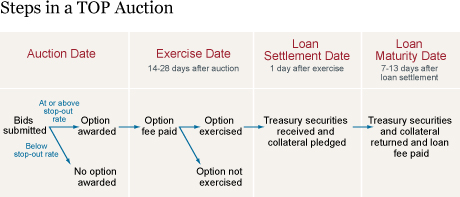

Auction terms were announced one to two weeks before the auction date. Announcements included information such as auction start and close times, expiration date, exercise date and time, loan settlement and maturity dates, and loan fee. Auctions started at 2:00 p.m. eastern time on the specified date and lasted for thirty minutes. Options awarded could be exercised at 2:00 p.m. on the option expiration date.

While all primary dealers were eligible to participate in the TOP, bidding was not required and, in fact, not all dealers bid in the auctions. Primary dealers could submit up to two bids, each consisting of a dollar amount of options to be purchased and a rate to be paid as an option fee. Dealers could bid for up to 20 percent of the offering at any given auction, with a minimum bid of $10 million. Bid rates were submitted in increments of basis points, with a one basis point minimum.

Options were awarded starting with the highest-rate bid and continuing until the total auction offering had been filled, or the bids had been exhausted, whichever came first. Options could be awarded for the full bid amount, a partial amount (in $1 million increments), or not at all. The lowest accepted bid rate at each auction was called the stop-out rate. Because TOP auctions were held in a single-price format, all awardees paid this stop-out rate as the option fee, regardless of their actual bid rates. Option fees were due on the exercise date—whether the primary dealer chose to exercise in full, in part, or not at all.

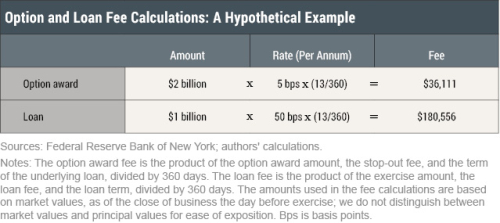

Primary dealers that chose to exercise their options also paid a loan fee on the loan maturity date (see chart below). Unlike the auction-determined option fee, the loan fee was disclosed by the Fed when the auction terms were announced. Both the option fee and the loan fee were set at annualized rates, so that dealers only paid the fraction of the annual rate corresponding to a seven- or thirteen-day loan term.

The loan fee was set at 25 basis points for the end-September 2008, end-March 2009, and end-June 2009 dates, and 50 basis points for the end-November 2008 and end-December 2008 dates. TOP loan fees were set to be higher than what would arise in a normal market situation to encourage primary dealers to borrow from other sources before transacting with the Fed.

As a hypothetical example, suppose a dealer won $2 billion in options for the end-December 2008 exercise date (see table below). The stop-out rate, as determined in this auction, was 5 basis points (per annum, based on the thirteen-day term of the loan) and so the dealer would have paid a $36,111 options fee. If the dealer had then exercised half of the option award amount, with a per annum loan fee of 50 basis points and a thirteen-day term, the dealer would have paid an additional $180,556 loan fee.

A Unique Liquidity Option

The TOP’s unique options feature enabled dealers to insure themselves against potential funding difficulties during the crisis without committing themselves to borrowings they might not need. But to what extent did dealers bid for liquidity options and at what fees? And did the dealers exercise their options? And is there anything we can say about which dealers participated? We address these questions in our next post.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Erin Denison is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Erin Denison is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael J. Fleming is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Warren B. Hrung is an officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Erin Denison, Michael J. Fleming, Warren B. Hrung, and Asani Sarkar, “Options of Last Resort,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), February 26, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/02/options-of-last-resort.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you both for your comments. In response to Yaw’s question about possibly changing collateral value, the program required that collateral be valued daily by the clearing bank. Adjustments to collateral levels might then need to be made to maintain the designated margin amounts. For additional details on the program’s terms and conditions, see: https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/tslf_terms.html.

The FED/Treasury should ensure that collateral is not at risk, for a repo transaction, even under a worst case scenario. The market knowing this up front, will not seize.

‘The TOP’s unique options feature enabled dealers to insure themselves against potential funding difficulties during the crisis without committing themselves to borrowings they might not need.’ At a lower cost too compared to accessing the other liquidity facilities. I would think that it would be much more cost efficient (during the crises) to pay $36,111 to have the option to get access to $2B, as in the example provided, when needed. ‘Also as in the TSLF, a broad range of highly rated securities were accepted as eligible collateral. ‘ What happens if the highly rated assets pledged decreases in value? For example if the dealer pledge AAA CDOs, which took a beaten during the crises? Looking forward to the next post.