Several countries have implemented a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system to establish high carbon prices and create a disincentive for the use of fossil fuels. Essentially, the tax encourages firms to substitute toward low carbon emission energy. Costs also rise for firms down the supply chain that use production inputs with high-emission content, so the total impact of a carbon tax can be large. In practice, however, firms also have an incentive to find an offset to a carbon tax. In this post, based on our recent work, we present evidence of one such adaptation strategy. We show that French firms increased their imports of high-emission inputs from suppliers outside the European Union’s cap-and-trade system, known as the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), reducing the effectiveness of this approach to cutting carbon emissions—an adaptation strategy that leads to “carbon leakage.” To help stop this leakage, the EU is implementing a “carbon tariff” in 2026, which is the topic of a companion post.

The EU ETS and Carbon Prices

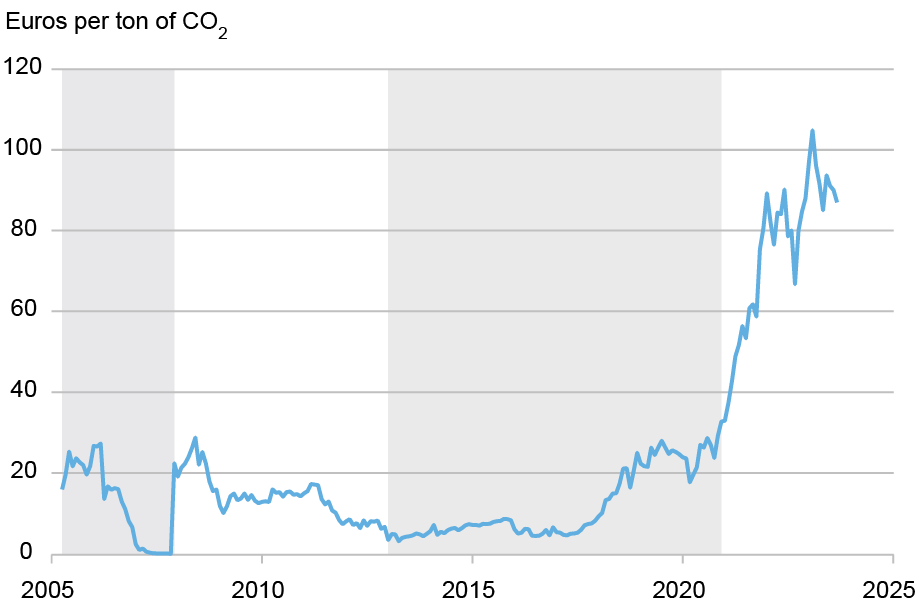

The EU ETS imposes a cap (limit) of emitted greenhouse gases for a set of firms in high-emission industries, such as steel production, chemicals, cement, or ceramic goods. These firms can bid on allowances to have larger emission limits via a centralized auction system. These allowances are then traded on the ETS market, setting a market price for carbon emissions. The implementation of this system began in 2005 and has evolved over three phases to be more stringent. The chart below shows the evolution of the carbon price over time due both to changes in ETS policy and growth in economic activity.

Carbon Prices in the EU ETS Have Moved Higher over Time

Notes: The chart is constructed using the end-of-month value of the closest carbon futures contract series sourced from ICE. Each shaded and nonshaded area represents a phase of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).

How We Define Regulated Goods and Sourcing Choices

We construct a new dataset that classifies “unregulated” and “regulated” manufacturing goods by leveraging information about the scope of the European policies. That is, we define a list of regulated inputs based on whether these goods are covered by the ETS. We merge the list of regulated goods to French firms’ import data to study where firms source unregulated and regulated goods and how this behavior has changed over time. By focusing on firms’ imports usage, we capture the indirect impact of a policy on downstream customer firms.

Outsourcing High-Emission Inputs Along the Supply Chain

We draw from this dataset to study whether the ETS generated more regulated imports. The use of detailed information allows us to control for common trends and other economic forces that may be driving patterns observed in French imports, and which would make it difficult to identify the impact of the ETS on firm behavior. Specifically, we analyze our dataset across three dimensions—importing firm, source country, and product type—to identify how firms have changed their relative sourcing of regulated imports from non-ETS countries.

We estimate panel regressions and consider two margins of adjustment as a dependent variable. The first measure is the import share of a given input relative to total firm imports. The second measure is a dummy variable that indicates whether a firm begins to source a product from a new source country. An increase in either of these two variables for regulated goods relative to unregulated goods would indicate undercutting of the ETS by firms. To capture this effect in our regression, we include an independent variable that interacts a time dummy with a dummy variable indicating whether an input sourced from a non-ETS country is regulated or not. We further include an array of fixed effects to control for common trends and other unobserved variables that may otherwise bias our estimates.

Our regression estimates indicate that French firms increased their sourcing of regulated inputs from non-ETS countries over time, with that sourcing increasing substantially as carbon prices started to rise. This carbon leakage is economically significant: the share of ETS-regulated products sourced from outside the EU rose by 4.3 percentage points between 2004, the year before the ETS was implemented, and 2019. Further, this increase was in part driven by a 3.6 percentage point rise in the probability of a firm starting to import regulated goods from non-ETS countries. These estimates confirm that French firms increased their sourcing of regulated goods from outside the ETS over time and thus reduced the effectiveness of the ETS.

Conclusion

This post shows why domestic carbon policy may not be as effective as intended in decreasing global emissions, since firms can adapt in an open economy by changing their sourcing behavior—which simply shifts where high-emission content inputs are sourced from and does not decrease their global production.

Other policies, such as carbon tariffs, can help solve this problem at the border. In a companion post, we examine the welfare consequence of such a tariff that is about to be implemented—the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

Pierre Coster is an economics Ph.D. student at the University of Southern California.

Julian di Giovanni is an economic research advisor in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Isabelle Mejean is a professor of economics at Sciences Po.

How to cite this post:

Pierre Coster, Julian di Giovanni, and Isabelle Mejean, “What Can Undermine a Carbon Tax?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, January 7, 2026, https://doi.org/10.59576/lse.20260107a

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics