Japan’s general government debt-to-GDP ratio is the highest of advanced economies, due in part to increased spending on social services for an aging population and a level of nominal GDP that has not increased for two decades. The interest rate payments from taxpayers on this debt are moderated by income earned on government assets and by low interest rates. One might think that the Bank of Japan’s purchases of government bonds would further ease the burden on taxpayers, with interest payments to the Bank of Japan on its bond holdings rebated back to the government. Merging the balance sheets of the government and the Bank, however, shows that the asset purchase program alters the composition of public debt, with reserves in the banking system replacing government bonds, but not the amount of the debt taxpayers must pay interest on.

Debt Burden after Decades of Government Borrowing and No Growth

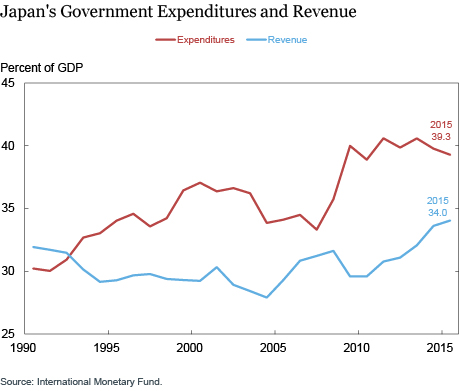

Japan’s government has been a net borrower since 1993. The chart below shows the persistent gap between revenue and expenditures, both represented as a share of GDP, as calculated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Expenditures trended higher over the course of the 1990s while revenues trended down. Part of this gap is due to efforts to offset the dramatic slowdown in growth, which fell from an average annual rate of 4.5 percent in the 1980s to 1.5 percent in the 1990s. Another factor behind deficit spending is that higher health care costs from an aging population and higher health care prices put upward pressure on total expenditures, with government health care spending rising from 4.5 percent of GDP in 1990 to 9.5 percent in 2010, according to IMF estimates. More recently, the government increased its spending during the global financial crisis to sustain growth and then implemented an increase in the sales tax in April 2014 to narrow the budget deficit.

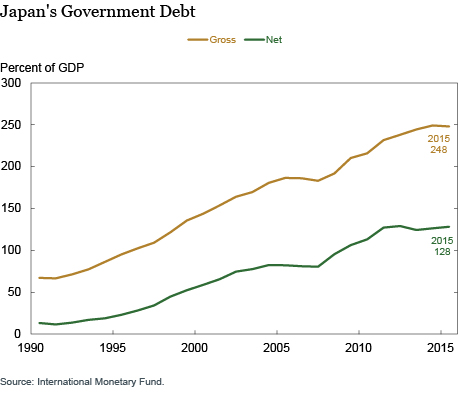

As seen in the chart below, decades of government borrowing and essentially no change in nominal GDP caused the country’s gross debt to rise to 250 percent of GDP in 2015. Among advanced economies, the next highest debt level is Greece (197 percent), followed by Portugal (128 percent). This very high debt level means that a 1 percentage point increase in interest rates on government debt would cause the share of taxes required to pay interest on the debt to rise by an amount equal to 2.5 percent of GDP.

Fortunately, the situation is not so dire since the government earns income from its asset holdings, making net debt a more appropriate measure of the tax burden. The Japanese government owns equity shares, has deposits in banks, and holds the country’s foreign exchange reserves ($1.2 trillion as of April 2016). This last entry is somewhat unique, as most advanced economies put their foreign exchange reserves on the central bank’s balance sheet. In addition, a substantial amount of government debt is held by other parts of the government. Together, these assets produce a net debt of 126 percent of GDP. By comparison, Greece has net debt equal to 194 percent of GDP while Portugal has net debt equal to 121 percent.

The Changing Composition of Public-Sector Liabilities

Very low interest rates and earnings on government assets meant that net interest on government debt was equal to only 0.5 percent of GDP in 2015. Indeed, the calculation overstates net interest since it includes the interest paid to the Bank of Japan, which was then rebated back to the government.

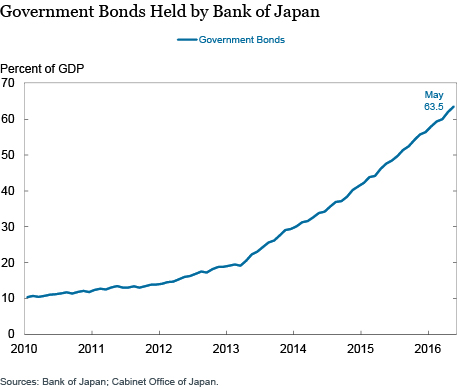

The issue of interest paid to the central bank has become increasingly important in the last few years. As seen in the chart below, the Bank of Japan’s asset purchase program has substantially increased the amount of government bonds it holds from the equivalent of 20 percent of GDP when the program started in early 2013 to about 65 percent today. (For comparison, Treasury bonds on the asset side of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet rose from an amount equal to 5 percent of GDP in 2007 to 13 percent today.) The program has the Bank buying government bonds and paying for them by issuing reserves to commercial banks, which they hold in their accounts at the central bank. As a consequence, the Bank of Japan is enlarging its balance sheet, increasing its assets (government bonds) and its liabilities (reserves). The amount of funds that the Bank rebates back to the government depends on the difference between the interest earned on the bonds and the interest the Bank pays on reserves.

The implications of the program for taxpayers become clearer if one considers the Bank of Japan as part of the public sector and merges its balance sheet with that of the government. The government bonds purchased by the Bank of Japan are added to the asset side of the consolidated public-sector balance sheet, which allows them to be eliminated since these bonds are now both assets and liabilities. What is left on the combined balance sheet are the bank reserves that were used to buy the bonds. The end result is that the size of the public sector’s debt is unchanged even though the amount of government bonds held by the private sector shrinks.

Reserves are essentially very short-term government bills held only by commercial banks with the interest rate set by the Bank of Japan. It may look like the taxpayer benefits from having interest on government bonds going to the Bank of Japan, but this view misses the fact that interest is being paid on a matching increase in bank reserves. The point is that this form of debt is not free to taxpayers, with the Bank of Japan using the interest earned on its government bond holdings to pay interest on the reserves that banks hold. Only the difference gets sent back to the government.

The taxpayer does gain since the asset purchase program shortens the maturity of public-sector debt, which given the term premium on long-term bonds, lowers the amount of interest payments on this debt. Note that the story can get more complicated whenever short-term rates rise significantly above long-term rates, as Marco Del Negro and Christopher Sims explained in an earlier post on “Central Bank Solvency and Inflation.”

Epilogue: Monetizing Government Debt

The discussion above offers up a perspective on what is meant by “monetizing debt.” This term refers to a central bank buying government bonds and promising to keep them on its balance sheet with the result that the increase in reserves in the banking system translates into higher prices. This outcome, though, requires that the central bank not pay the appropriate interest rates on reserves. If it does, then an asset purchase program is just an effort that shortens the maturity of public-sector debt and will likely have few or no implications for future inflation.

The authors thank Peter Stella for helpful discussions.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Research and Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Harry Wheeler is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Thomas Klitgaard and Harry Wheeler, “The Rapidly Changing Nature of Japan’s Public Debt,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), June 22, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/06/the-rapidly-changing-nature-of-japans-public-debt.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

In reply to Gary Haubold: Your alternative, of the central bank buying bonds directly from the government, does not keep reserves from being created in the banking system. In your example, the government gets funds directly from the central bank in exchange for bonds. But the government then spends this money and the recipients deposit these funds in a bank, so even a direct transaction between the central bank and the government does not change the story presented here.

If you don’t mind, a follow-up question regarding Japan’s future monetary policy. In the 1930s under the leadership of Finance Minister Takahashi Korekiyo, Japan left the gold standard in December 1931 and devalued the Yen, and took the unusual further step of having the Central Bank purchase new issue government bonds directly from the Treasury – with the proceeds used to fund increased military spending and accelerated public spending programs called ’emergency relief expenditures (jikyoku kyokyuhi). My understanding is that the program was very successful – until February 1936 when a revolt of army officers unhappy about planned cutbacks in defense spending assassinated both Mr. Korekiyo and former Prime Minister Saitō Makoto. My question then, “If the Bank of Japan buys government bonds directly from the Treasury, are there no reserves created in the banking system”, making this a superior method of Quantitative Easing or whatever term one wishes to use to describe it?”

In reply to Gary Haubold: The framework presented here shows the problems with monetizing the debt by promising to never pay interest on reserves. This scenario puts the debt burden on the banking system, which will have to lower interest paid on deposits or raise fees to offset being required to hold assets that have no rate of return. It is not clear if the banking system would survive, with the stress rising every time interest rates move higher. Similarly, eliminating reserves entirely would essentially be wiping out a substantial amount of bank assets.

Trying to rephrase Mr. Watzka’s question a bit: If the balance sheets of the BoJ and the Japanese government are merged, the government debt cancels out but reserves remain as liabilities – essentially very short term government IOUs which are also held as assets by Japanese commercial banks only and which pay interest at a rate determined by the BoJ. If the BoJ were to announced that (a) it intended to hold the liabilities in perpetuity, and (b) that the rate of interest on those reserves would be zero, how is that different from eliminating the reserves entirely?

In reply to Sebastian Watzka: Negative rates on reserves are consistent with negative rates on short-term government securities since they are similar forms of public debt. These rates are indeed reducing the size of the public debt, but this is separate from considering the benefits of shortening the maturity structure of public debt caused by the asset purchase program.

Interesting and very informative post on Japanese government debt and QE. Still, two questions come to my mind: i) The BoJ currently charges marginal bank reserves with -0.1. Shouldn’t you have at least alluded to the fact that reserves that are parked with central banks are currently actually a source of INCOME to the central banks, and hence to society. Besides, the central bank has (almost) full discretion as to how negative it sets its deposit rate. ii) How does helicopter money fit into this story ? Wouldn’t that again be a cheap way of financing socially benefitial public infrastructure projects (at least as long as deposit rates are negative) ? And remember, the central bank can of course always stop printing money. In other words, I believe you are a little unfair to the potential positive effects of QE and helicopter money. Having said that, I of course understand that there are risks involved and central banks might not want to go that way. Would be very interested to hear your views on my two questions. Thank you !