Since the height of the financial crisis, each year the Federal Reserve has disclosed the results of its stress tests, and stress testing has become “business as usual” in the U.S. banking industry. In this post, we assess whether market participants find supervisory stress test disclosures informative. After half a decade, do the disclosures still contain information that the market finds valuable?

How Could the Stress Test Disclosures Not be Informative?

It seems intuitive that the disclosure of supervisory stress test results would contain useful information for investors and other market participants. That’s because the stress tests are based on confidential information provided by bank holding companies (BHCs) and calculations made by supervisors. Some commentators have argued, however, that the U.S. stress tests have become predictable, offering little new information from year to year. Further research examining the market reaction to stress test disclosures has produced mixed evidence. Some studies find that even in recent years, stress test disclosures still significantly affect market prices, while others find that the price impact has declined significantly. Even in studies that determine there is a significant market reaction, some have found the reaction to be positive and some negative.

This mixed evidence might be the result of the way “market reaction” is calculated. Many of these studies use an event study technique that measures the “abnormal return” in a bank’s stock price around the time of the disclosure relative to the overall market return (while accounting for the usual relationship between the bank’s stock return and the market return). The abnormal returns will be positive or negative depending on whether the information disclosed was better or worse than investors expected. Most event studies calculate the average abnormal returns for a group of firms (banks in this case), assess whether the average abnormal return is significantly positive or negative, and interpret this average as a measure of the informativeness of the disclosures. These average abnormal returns mean that large positives and large negatives can cancel each other out.

Absolute Measures of Market Impact

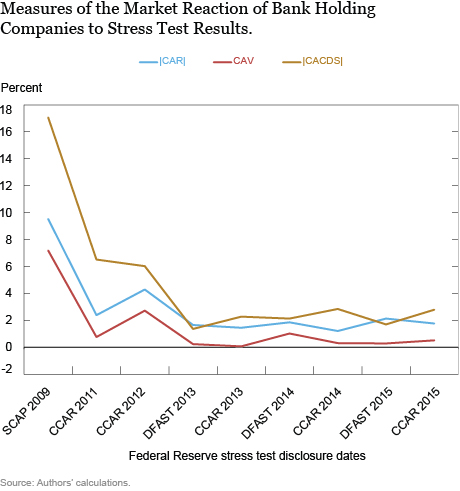

In a recent research paper, we examine alternative measures of market reaction to stress tests. We start by examining the average absolute value of the cumulative (over 3 days) abnormal change in share prices (|CAR|) around stress test announcements. This measure should be larger than its normal value on days without announcements if investors react to the stress test results, even if positive and negative effects were evenly distributed across the sample. All else equal, absolute abnormal returns will be larger the more new information is revealed by the stress test disclosures. We calculate abnormal returns using a three-factor model to account for the fact that the stress-tested firms are large.

The second measure we examine is abnormal trading volume (CAV). This measure, which is similar to one used in the accounting literature and previous financial research, is based on the assumption that trading volume increases if new information affects investors’ prior beliefs. We measure abnormal trading volume as deviations in bank trading volume relative to what would be expected given marketwide trading volume.

We also look at measures from other public markets. Since stress testing is oriented toward performance in stressful macroeconomic and financial market times, the results may be more informative for instruments—such as credit default swaps (CDS)—that vary more with downside risk. Thus, we examine changes in CDS spreads, again taking the absolute value cumulative abnormal spread change, |CACDS|.

We calculate these measures for each of the nine dates on which the Federal Reserve disclosed stress-test-related assessments of large banks. These dates begin with the original stress test disclosure in May 2009 (the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program, or SCAP) and continue with the annual disclosures associated with the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) starting in 2011 and the related Dodd-Frank Act stress test (DFAST) disclosures starting in 2013.

Does the Market Continue to React to Stress Test Disclosures?

Our results suggest that the market response to supervisory stress test disclosures remains significant even for disclosures in recent years. The chart below presents our absolute value of cumulative abnormal returns|CAR|, cumulative abnormal trading volume CAV, and absolute value of cumulative abnormal CDS spread change |CACDS| results graphically for the stress-tested banks across the nine SCAP, CCAR, and DFAST disclosure dates. These measures are highest for the original SCAP disclosures in 2009. They have declined since their most recent peak in 2012, and remained roughly equal for the 2013, 2014, and 2015 disclosure dates. Although the measures have decreased since 2012, the hypothesis that the values are the same (and non-zero) for the 2013 to 2015 disclosures cannot be rejected.

In summary, we find that while the size of the market reaction to U.S. supervisory stress test disclosures has decreased since the 2009 SCAP, the disclosures seem to provide meaningful information to investors and other capital market participants—even for the recent stress test results. Our findings suggest that supervisory stress test disclosures continue to provide new information, in addition to serving as a supervisory mechanism for assessing the capital adequacy of large, complex BHCs.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Beverly Hirtle is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group

Anna Kovner is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Samantha Zeller is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Samantha Zeller is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics