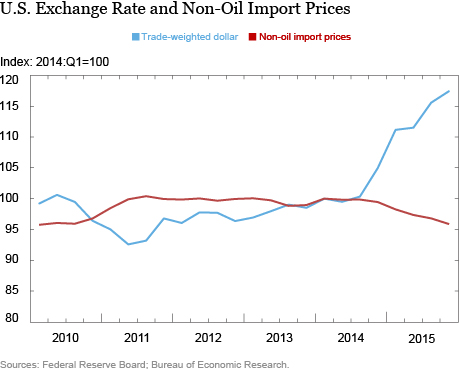

Changes in exchange rates directly affect import prices. Since the beginning of 2014, the U.S. dollar has strengthened by 17 percent against the currencies of its major trading partners while import prices have fallen by 4 percent. The pass-through from exchange rates into import prices in the United States is estimated to be quite low, at around 30 percent, and this is often attributed to the fact that imports are mostly invoiced in U.S. dollars. In addition to this direct impact of exchange rates on import prices, there can also be an effect on domestic prices. Suppose that a stronger U.S. dollar means that cars imported from Japan will be cheaper for U.S. consumers. If domestic auto producers do not then reduce their U.S. prices they could lose market share. By how much do they adjust their prices? In this post, we draw on a new study—“International Shocks and Domestic Prices: How Large Are Strategic Complementarities?”—that uses micro-level data for Belgian firms to shed light on this question.

An exchange rate shock can affect domestic prices through two distinct channels. The first is a direct effect through the marginal cost channel, as the exchange rate alters the price of imported inputs. Continuing with our car industry example, a stronger U.S. dollar makes imported intermediate inputs—such as car parts, steel, and rubber—cheaper so the marginal cost of producing a car in the United States is lower. This effect will be larger for firms that source a larger share of their inputs from abroad. The second, more indirect effect, is through the markup channel. Imported final goods, foreign cars for example, are also cheaper due to the strong dollar. As a result, domestic car producers may lower the price of cars produced for the U.S. market in order to maintain market share even if they do not import intermediate inputs. That is, domestic prices of final goods may change purely in response to a change in competitor prices—even without any change in their marginal costs. This would result in lower markups for U.S. firms. We refer to this effect as strategic complementarities.

Our study uses micro-level data for Belgian firms to estimate strategic complementarities for a broad range of manufacturing industries, based on their sales in Belgium. Although Belgium has a higher import share than the United States, and thus has a higher exchange rate pass-through into import prices, we expect that the same economic forces determine how firms set prices in other market-based economies. We use the Belgian data because it contains detailed information on firms’ domestic prices, marginal costs, and competitor prices, which are necessary to estimate strategic complementarities. We use these empirical estimates to explore aggregate exchange rate pass-through in counterfactual industries that are not typical in Belgium manufacturing, but more characteristic of other countries. In addition, we study the determinants of industry-level pass-through. Our study finds a number of interesting results.

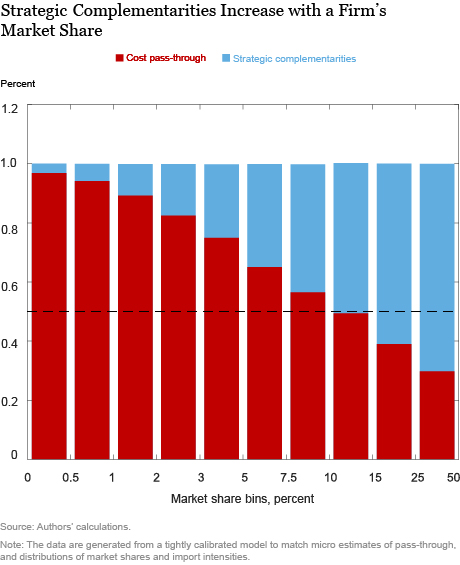

First, we provide strong evidence of strategic complementarities in price setting. Firms adjust their prices by 0.3 percent in response to a 1 percent change in their competitors’ prices even if there was no change in their own marginal costs. Beneath these average effects, we uncover a great deal of heterogeneity. Small firms (defined as having less than 100 employees or less than 2 percent market share within their industry) do not respond to changes in competitor prices, whereas large firms adjust their prices with an elasticity of 0.5. Interestingly, small firms only adjust their prices in response to shocks to their own marginal costs. We can see this in the chart below, which shows the strength of strategic complementarities increasing with a firm’s market share.

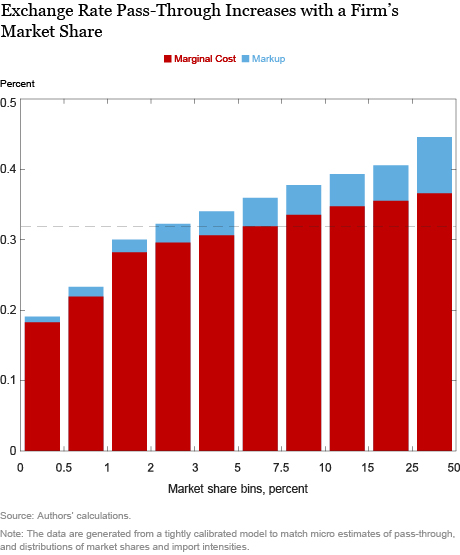

Second, large firms exhibit higher exchange rate pass-through into domestic prices than small firms. This happens for a couple of reasons. Large firms source a higher share of inputs from abroad than small firms so their marginal costs are a lot more affected by exchange rate movements. In the chart below, this can be seen by the larger red bars for firms with a bigger market share. In addition, large firms have stronger strategic complementarities and thus actively move their markups in response to foreign competition, which is shown by the larger blue bars as we move to the right of the chart.

What are the implications of these results for the U.S. economy? They suggest that U.S. domestic prices are likely to respond more strongly to an appreciation of the U.S. dollar in industries with high import intensity, which pushes down marginal costs, or a high share of foreign competition, which pushes down competitor prices. These strategic complementarities are larger in industries with a low correlation between import intensity and firm size. That is, large firms will reduce their markups more, to maintain market share, if their marginal costs are not hit by the same shock as their competitors. To the extent that most U.S. sectors are dominated by domestic firms, or firms from countries that invoice in U.S. dollars, we would expect little strategic complementarity effect through the markup adjustment of U.S. firms. This, however, can be very different in industries that have more significant foreign competition.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Mary Amiti is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Mary Amiti is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Oleg Itskhoki is a professor of economics at Princeton University.

Jozef Konings is a professor of economics at the University of Leuven in Belgium.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Interesting article. In my empirical experience as a consumer, it feels like firms are much more likely to pass along price hikes than price declines. Does the study cited address the potential asymmetry between a rising exchange rate vs. a falling exchange rate?