Adam Kirk, James McAndrews, Parinitha Sastry, and Phillip Weed

This post is the eighth in a series of thirteen Liberty Street Economics posts on Large and Complex Banks. For more on this topic, see this special issue of the Economic Policy Review.

The failure or near-collapse of some of the largest dealer banks on Wall Street in 2008 highlighted the profound complexity of the industry. In some ways, dealer banks resemble well-understood traditional banks, which use deposits they receive from savers to make loans to businesses and households. Unlike traditional banks, however, dealer banks rely on complex and unique forms of collateralized borrowing and lending, which often involve the simultaneous exchange of cash and securities with other large and sophisticated financial institutions. During normal times, such transactions are highly efficient methods for allocating scarce resources. During times of stress, in contrast, they’ve proven to be destabilizing for the individual firms and, as recent history has shown, the financial system at large.

Dealer banks often receive collateral in connection with their lending and market-making activities. In many cases, the collateral received is permitted to be repledged in transactions that generate financing for the dealer bank. Dealer banks, aiming to maximize their income and minimize the cost of various regulatory constraints, optimize their business model by matching their sources and uses of collateral. The benefit from the reuse of collateral, namely the ability to secure additional low-cost financing, is enhanced when a dealer bank efficiently intermediates between those clients that demand cash and possess securities and those that demand securities and possess cash. In our contribution to this Economic Policy Review series, we focus on three categories of secured activities that exemplify such efficiencies: matched-book dealing, cash brokerage internalization, and derivatives dealing.

Matched-Book Dealing

Dealer banks often refer to a balance sheet in which repurchase agreements finance offsetting reverse repurchase agreements as a “matched book.” In a typical matched-book transaction, a client provides a security as collateral in exchange for cash and grants the dealer the right to repledge this collateral; the dealer then repledges this security to another client to source the cash. As a result, the dealer’s balance sheet does not reflect any security owned, though it does reflect both a claim to cash and an obligation to return cash at a future date. In practice, “matched-book” transactions aren’t always as perfectly “matched” as the name suggests; dealer banks often engage in significant amounts of maturity, credit, and collateral transformation, exposing them to interest rate, liquidity, and credit risk.

Cash Brokerage Internalization

In some cases, dealer banks can source financing “internally” via naturally offsetting client trading positions. Opportunities to “internalize” can arise when the dealer extends a margin loan to a client, which is collateralized by the purchased security. If this collateral is then repledged for an opposing client’s short position in the same security, then in effect the second client’s short position finances the margin loan, while the collateral from the margin loan satisfies, or “finances,” the short position. Though internalization resembles “matched-book” financing, it differs in that it’s generally more cost-effective for the dealer bank, allows for a greatly reduced balance sheet (when compared to the gross financing provided by the dealer), and is able to generate funding for a dealer bank’s own trading positions. As we describe below, this increased efficiency is accompanied by more complex risks.

Derivatives Dealing

The final category of dealer bank activity examined in this post is collateralized derivatives dealing. A dealer bank that has sold a derivative to a client can purchase an equal and opposite exposure from another dealer bank, using the collateral received from one transaction to satisfy the collateral requirement of the second while potentially capturing a small income spread. Unlike the other secured transactions mentioned above, these derivatives transactions don’t entail the exchange of cash for securities. However, they do require the posting or receipt of collateral (often cash) to secure a synthetic economic exposure. Asymmetries in the contractual terms pertaining to the extent of collateralization may give rise to situations where dealer banks receive more collateral than they post. This generates excess capacity, which dealers can exploit by repledging the excess collateral to finance additional income-earning transactions.

Unique and Complex Risks

The interdependence of the lending to one customer and the collateral posted by another makes the intermediation by dealer banks vulnerable in ways that are different from that of traditional banks. In a traditional bank, when a borrower repays a loan, the bank can often redeploy the repaid funds as a loan to another borrower or as payment to a depositor. In contrast, when a borrower repays the dealer bank, the borrower also reclaims the collateral it posted to the bank. If the dealer had repledged this collateral to satisfy a second customer’s demands, it must find a suitable substitute for the reclaimed collateral or unwind the second customer’s transaction. Finding a substitute at equivalent cost can be difficult in an illiquid market, and deleveraging the second client’s position could potentially damage the dealer bank’s reputation.

The Evidence

Under specific conditions specified by U.S. GAAP, the transactions described above are often eligible for balance-sheet “netting.” As a result, the reported size of the dealer’s balance sheet may not completely capture its gross risk exposures. Here, we’ve estimated dealer banks’ gross risk exposures by the size of their collateral stock, using data reported in their public SEC disclosures. In general, risks may materialize when dealer banks use an unstable pool of collateral to finance the longer-term needs of their clients or, conversely, employ short-term and unstable liabilities to finance illiquid collateral positions.

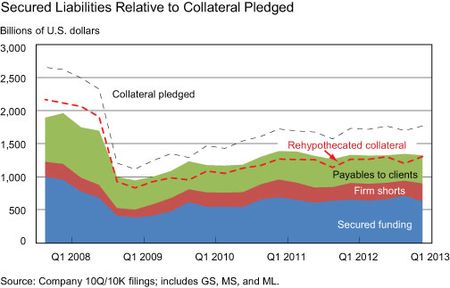

The importance of matching sources and uses of collateral is emphasized by the level of collateral repledged relative to secured liabilities and in normal times represents how efficient the dealer banks are in economizing on collateral. During the crisis, however, there was a precipitous drop in collateralized financing. The chart below reveals that between 2007:Q4 and 2008:Q4, total collateral pledged declined by nearly $1.5 trillion, or a 55 percent decrease. Of this, the level of collateral repledged fell by $1.2 trillion, or 57 percent, over the same period. At the same time, on-balance-sheet secured liabilities declined by a much lower amount—$897 billion, or a 47 percent drop. The accelerated decline of collateral pledged and collateral repledged suggests a sort of collateral scarcity, resulting in dealer banks pledging more of their own securities as collateral to secure funding (as well as relying on uncollateralized funding or increases in equity).

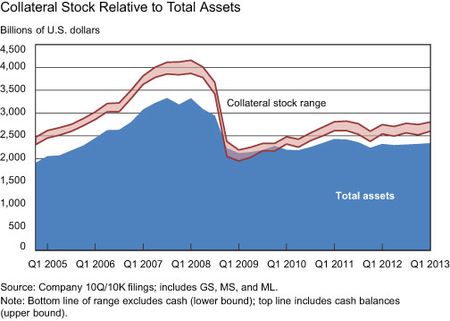

Additionally, we can observe in the chart below that dealer banks tend to generate stocks of collateral in excess of their total balance sheet during periods with stable market conditions, although this spread contracts acutely in response to market disruption. The stock of collateral for our sample of firms peaked in 2008:Q1 at approximately $3.9-$4.2 trillion in notional terms (116-125 percent of total on-balance-sheet assets). In other words, the firms extended financing to customers in excess of their on-balance-sheet reported lending by approximately 16-25 percent. However, in 2009:Q4, the stock of total collateral fell to $2.2-$2.3 trillion, or 95-103 percent of total on-balance-sheet assets. The drop in the total stock of collateral outpaced balance sheet deleveraging in both notional and percentage terms, falling by $1.7-$1.8 tr

illion, or negative 44 percent, versus a $1 trillion, or negative 31 percent change, in total on-balance-sheet assets. Thus, for dealer banks, balance-sheet declines understate the total contraction of secured financing activity.

Conclusion

The evidence suggests that the financial crisis was especially troubling for dealer banks. The collateral they had received from customers disappeared when customers exited positions that the dealer bank had financed. Because dealer banks had heavily utilized the customer-provided collateral, they were forced to source securities and cash externally to manage and meet their obligations at the same time that markets were most disturbed. That the amount of financing extended by dealer banks fell further and more swiftly than the banks’ balance sheets suggests that a prudent risk management framework would acknowledge the risks inherent in collateralized finance, and allocate both capital and liquidity to address any shortfalls that could arise in a risk event. Furthermore, the efficiencies gained from dealer banking should be weighed against the social costs that accompany a systemic risk event. Further research on the role that dealer banks play in securities markets could shed light on such trade-offs.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Adam Kirk is a risk analytics associate in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Financial Institution Supervision Group.

James McAndrews is an executive vice president and the director of research at the Bank.

Parinitha Sastry is a former senior research associate in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Phillip Weed is a risk analytics associate in the Financial Institution Supervision Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics