Tobias Adrian and Nina Boyarchenko

The financial crisis of 2007-09 highlighted the central role that financial intermediaries play in the propagation and amplification of shocks. Intermediaries increase leverage during the boom, which then makes them more vulnerable to adverse economic developments. In this post, we review evidence on the balance-sheet behavior of financial intermediaries and describe a channel that allows intermediaries to increase leverage during booms when asset market volatility tends to be low, which in turn forces them to dramatically reduce leverage once volatility increases. As shown during the financial crisis of 2007-08, the contraction of intermediary leverage is accompanied by increases in borrowing rates for households and a contraction of credit. The formal modeling of this amplification mechanism allows a welfare analysis of the tightness of regulatory capital requirements. We find that while loose capital constraints generate excessive risk-taking by intermediaries, tight funding constraints inhibit intermediaries’ risk-sharing and investment functions, which then lowers welfare.

Intermediary Leverage Is Procyclical

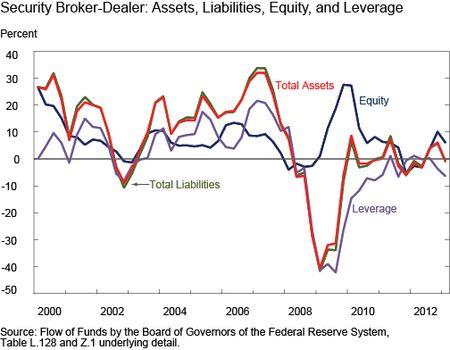

The first chart (below) plots the growth rates of book assets, liabilities, equity, and leverage for security broker-dealers. Security broker-dealers’ balance sheets are informative, as these intermediaries operate at the heart of financial markets. The chart shows that leverage tends to grow when balance sheets expand. This is the procyclical nature of intermediary leverage: intermediaries increase leverage when their assets are expanding, reflecting the expansion of economic activity. The chart also shows that broker-dealers finance their new assets by issuing new liabilities, not by raising new equity. During the crisis of 2008-09, broker-dealers reduced their leverage drastically by selling assets and raising new equity.

Intermediary Leverage Is a Pricing Factor for Asset Returns

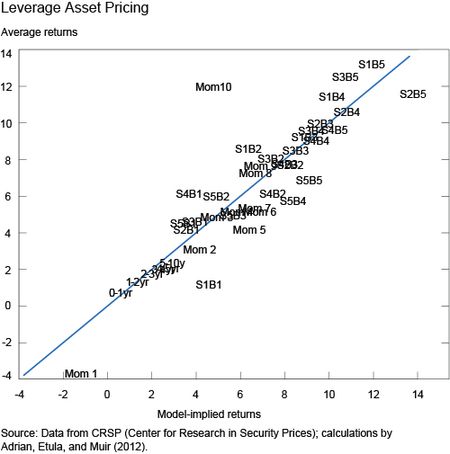

Broker-dealer leverage is an explanatory variable for asset valuations. Adrian, Etula, and Muir (2012) show that the covariations of stocks and bonds with intermediary leverage explain the average returns of these assets. Intuitively, a corporation whose stock return covaries positively with intermediary leverage faces systematic risk. For investors to bear this systematic risk, returns, on average, have to be high. The second chart (below) illustrates this by plotting predicted expected returns against average expected returns for a variety of stock and bond portfolios. Note that the predicted returns on the x-axis align very closely with realized average returns on the y-axis. The predicted returns are computed from the covariation of each security with broker-dealer leverage growth. Assets that covary more strongly with intermediary leverage changes earn higher returns on average. This finding illustrates that the price of leverage risk is positive, reflecting the procyclicality of leverage.

Intermediary Leverage Is Negatively Related to Intermediary Value-at-Risk

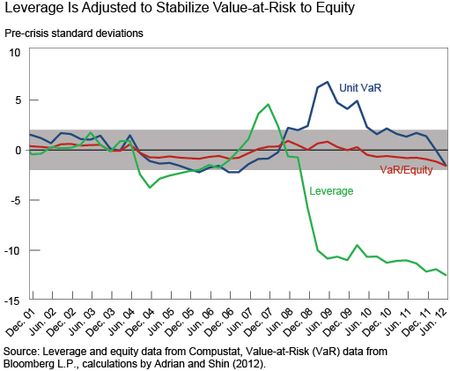

We show in a recent staff report that the functioning of financial intermediaries’ risk-based capital constraints can explain both the procyclical nature of intermediaries’ balance sheets and the positive relationship between intermediary leverage and expected asset returns. In practice, capital is allocated across trading and banking activities using risk management systems based on Value-at-Risk (VaR). Such risk management techniques allow financial institutions to take on more leverage when market volatility is low, and, vice-versa, to contract leverage when market volatility increases. In fact, a look at the intermediary balance sheet management shows that the leverage for the security broker-dealer sector follows such VaR rules closely. The third chart (below) shows VaR scaled by total assets (Unit VaR), and VaR scaled by book equity (VaR/E). Times of low VaR correspond to times of high leverage, while times of high VaR correspond to low leverage.

Value-at-Risk constraints were incorporated in the Basel II capital framework, which was adopted by major security broker-dealers in the United States—the investment banks—in 2004. Thus, capital constraints are imposed by regulation. In our staff report, we embed the risk-based capital constraint in a model with three sectors: a production sector (firms), a financial intermediary sector, and a household sector. Intermediaries serve two functions: 1) they create new production capacity through investment in the productive sector, and 2) they provide risk-bearing capacity to the households by accumulating wealth through retained earnings. The tightness of the capital constraint—measured by the maximal allowed ratio between intermediary leverage and one over the VaR on the intermediary’s assets—thus affects household welfare. When this ratio is decreased, the intermediaries are more restricted in their risk-taking and can therefore finance less investment. At the same time, since intermediaries take on less leverage and less risk, the systemic risk of the intermediary sector decreases. Accordingly, there is a trade-off between the amount of risk-taking and the price of credit in the real economy.

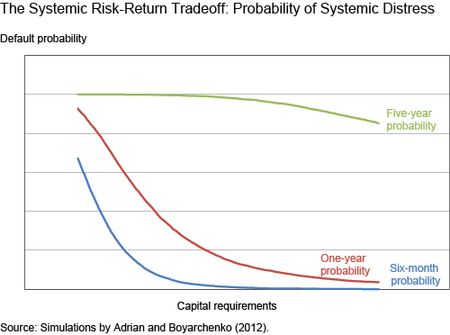

In the chart below, we plot the relationship between the probability of systemic distress at different horizons and the tightness of the capital constraints. This is the fundamental tradeoff faced by regulators within our model: Tighter capital requirements decrease the frequency and severity of systemic crises, but at the cost of lower average growth rates of consumption.

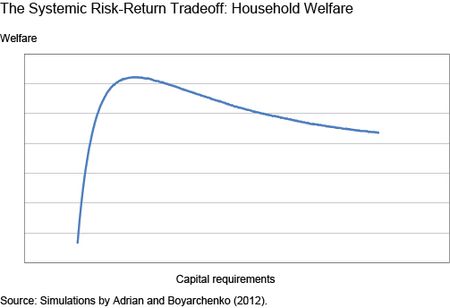

The next chart plots the theoretical relationship between household welfare and the tightness of the constraint. It shows that tightening capital requirements is beneficial when capital requirements are relatively low, as the benefits of lower systemic risk outweigh the costs of more expensive credit intermediation. However, capital requirements can be tightened too much, leading to a decline in welfare, as the cost of credit intermediation increases.

Implications for Bank Regulation

The tradeoff between the pricing of risk and the amount of systemic risk arises in our theory because tighter capital requirements constrain the ability of financial intermediaries to take on risk—thus reducing their ability to provide risk sharing to the household sector. The policy debate surrounding capital regulation can be understood in the context of this tradeoff. While some commentators believe that tighter capital requirements are expensive in terms of intermediation capacity of the financial system, others argue that it is cheap—or even costless—for financial institutions to reduce their riskiness by issuing equity. Quantitatively, the tradeoff between the pricing of credit and the amount of systemic risk is not well understood. Our framework provides guidance for empirical research to quantify this tradeoff.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Tobias Adrian is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Nina Boyarchenko is a financial economist in the Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics