Joseph Tracy and Joshua Wright*

In a recent speech, New York Fed President William Dudley called for actions “to see refinancing made broadly available on streamlined terms and with moderate fees to all prime conforming borrowers who are current on their payments.” This blog post explains how such a move could help stabilize the housing market and support economic growth. It also explains why mortgage refinancing is not—as some argue—a zero-sum game in which the benefits to one group are exactly offset by the costs to another.

Mortgage refinancing is one of the normal channels through which declining interest rates support economic activity, growth, and jobs. Falling mortgage rates reduce the amount of income households need to spend on servicing their home mortgages, freeing up cash flow for purchases of other goods and services.

For homeowners with adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), the required monthly mortgage payment declines automatically as the interest rate resets on the mortgage. This is a prominent and well-understood process in many other advanced economies—such as Great Britain—where ARMs make up the majority of the mortgage market.

For homeowners with fixed-rate mortgages—the vast majority of U.S. mortgage borrowers—the reduction in monthly payments takes place when the homeowner refinances the existing mortgage into a new mortgage at the lower prevailing mortgage interest rate.

When borrowers refinance and free up cash to spend, there will be an offset on overall economic activity as mortgage bonds are prepaid and investors in those bonds need to find alternative investments at precisely those times when other bonds are likely to offer a lower yield, reducing the investors’ income.

But we will argue that the offset is only partial. Why? There are two reasons. First, many mortgage bonds are held by government or foreign investors whose spending on U.S. goods and services does not depend to any significant degree on their income from the mortgage bonds. Moreover, the share of mortgage bonds held by such investors has increased. Second, the remaining, domestically based private investors are likely to cut back their spending much less than the borrowers raise theirs.

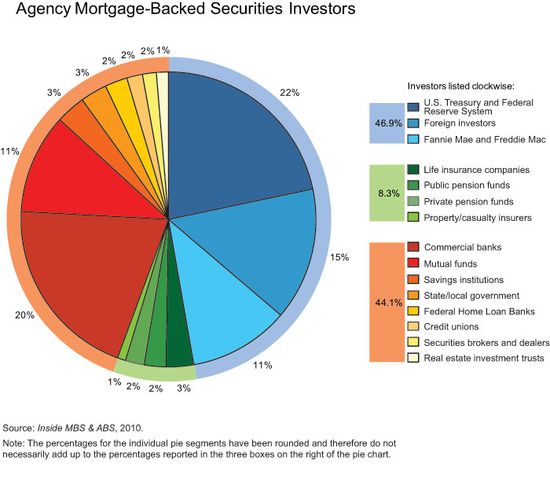

To better understand why the offset is only partial, let’s look at the figures in a bit more detail. As shown in the pie chart below, slightly less than 47 percent of agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are held by foreign investors and federal governmental institutions, including government-sponsored enterprises and the Federal Reserve. In these cases, we would not expect any domestic spending offset from a decline in the value of the MBS securities, for the reasons discussed above. An additional 8.3 percent of MBS are held by insurance and pension funds; for these funds, any spending effects are likely to be spread out over a relatively long period of time.

The fact that 55 percent of the investors are governmental, foreign, or long-term institutional holders suggests that each dollar of refinancing effectively translates into 44 cents of net increase in after-tax disposable income available for spending (= 0.55 x 80 percent, assuming a 20 percent marginal tax rate). If homeowners on average spend 90 percent of this additional disposable income, then each dollar of reduced mortgage payments would translate into 40 cents of additional spending.

However, this estimate of 40 cents per dollar is overly conservative, because the tendency for borrowers to spend out of increases in their disposable income likely exceeds the tendency for investor households to cut back spending in response to decreases in their interest income. For example, if investor households on average spend 70 cents of every dollar of after-tax investment income, then the overall impact of a dollar reduction in a borrower’s required monthly payment would increase by 7 cents [(=0.45 x 80 percent) x (90 percent – 70 percent)]—or from 40 to 47 cents. Taken together, these calculations imply that every dollar reduction in a borrower’s monthly mortgage payment stemming from a refinancing is likely to generate close to 50 cents of additional spending—a very different outcome than the absence of any change in spending implied if refinancing were a zero-sum game.

There is a second channel through which increased refinancing can support consumption: via its effect on house prices, wealth, and consumer confidence. Refinancing lessens the likelihood that a borrower defaults on a mortgage by creating additional cash flow that helps the borrower absorb any adverse income shock.

Thus, by reducing expected foreclosure sales, refinancing helps to restrain the downward pressure on house prices. Declining house prices lead to decreases in consumption by homeowners through a standard wealth effect, as well as the associated impact of house price expectations on consumer confidence.

Avoiding mortgage delinquencies can also avoid unnecessary loss of access to future credit, which could otherwise depress consumer spending for years to come and exacerbate challenges to fiscal rebalancing. For borrowers who go through a default and foreclosure, it often takes more than five years to rebuild their credit (Brevoort and Cooper 2010). During this period, the borrower’s consumption is reduced because of lack of access to credit, and when this behavior is widespread, aggregate economic activity declines.

Note that the effect of refinancing on consumption and jobs is shared broadly across the population of homeowners—including those that do not themselves refinance—and the economy as a whole. This improves economic outcomes for the nation and ultimately brings higher returns for investors as the economy expands and monetary policy is normalized. Thus, wealth and confidence effects also argue against the view of refinancing as a zero-sum game.

A number of commentators still argue that there is something unfair about refinancing. This is a strange objection to raise against mortgage refinancing specifically, since borrowers of all kinds—corporations and governments as well as households—refinance their debts when interest rates are low, freeing up cash flow to spend or invest. At the end of the day, investors and borrowers are parties to a set of contracts that accord this right of prepayment to the borrower, and the investor willingly accepts this risk—but at a price. Indeed, investors have been well compensated for this risk. Over the past two years, mortgage bonds have performed better than most models predicted because of greater-than-expected impediments to refinancing.

As we have shown, refinancing is not a zero-sum game and can benefit the entire economy. The greater the scale and scope of the refinancing program, the larger these benefits are likely to be. And these benefits are likely to be larger still if a broad-based refinancing effort is accompanied by other measures to help stabilize house prices.

*Joshua Wright is a senior trader/analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Response to posted comments: After reviewing some of the most recent comments, we would like to underline that our blog post was restricted to prime mortgages and so did not address a “mass refi” plan, such as the one advocated by Boyce, Hubbard, Mayer, and Witkin[http://www4.gsb.columbia.edu/null/download?&exclusive=filemgr.download&file_id=739308]. Refinancing activity could be facilitated simply by removing frictions to refinance – many of which lie in the hands of lenders, servicers, and mortgage bankers – that normally would not exist. That the government might act to help remove these frictions is not a violation of any of the GSEs’ covenants, and would be a risk that MBS investors assumed and have been compensated for. Removing these frictions would be working with market forces, not against them. John raises an important point in his comment. By virtue of the holdings of agency MBS by the Treasury and the Federal Reserve System, taxpayers are exposed to investment losses due to any streamlined refinancing program. The holdings of the Treasury and Federal Reserve System are designated by the dark blue segment of the pie chart, comprising roughly 22 percent of the total. Every dollar borrowers save on interest expense by refinancing implies a 22 cent reduction in investment income to the government. However, using our 20 percent tax rate assumption, the same dollar reduction in interest income will generate 20 cents of additional tax revenues (through lower mortgage interest deductions) – roughly offsetting the decline in investment income. In addition, since the federal government need not balance its budget year by year, it is also important to take a multi-year perspective. Since undertaking its large-scale asset purchases in Treasury and agency securities, the Federal Reserve’s remittances of excess income to the U.S. Treasury have risen sharply.* In other words, the Federal Reserve and Treasury holdings of agency MBS have benefitted just as other investors’ portfolios have (a dynamic we explained in the original post). Note that the Federal Reserve’s holdings – by far the larger of the two – have been concentrated in lower-coupon securities that would have faced low incentives to refinance until the most recent declines in mortgage rates. Dan asks what the ultimate impact of our 50 cents of increased consumer spending per dollar of lower monthly mortgage payments might be in terms of aggregate spending. The answer depends importantly on the details of both the program design and implementation. In addition, there is considerable uncertainty regarding the borrower take-up rate for any specific program – that is, even for those borrowers who do have access to lower mortgage rates, how many of them will take advantage of the opportunity? This makes calculating an aggregate spending effect difficult. What we have estimated is that a prime borrower with a current loan-to-value (LTV) below 80 who refinances would on average save $5,300 per year on mortgage payments. For a prime borrower with a current LTV above 80, the annual savings would on average be $3,500. Given any assumed number of refinancings from a program, these average savings and our 50 cents per dollar result would allow a rough calculation of the macro spending effect. *See http://www.nola.com/business/index.ssf/2011/01/federal_reserve_pays_us_treasu.html for a discussion and http://www.fms.treas.gov/dts/index.html for raw data.

Question…I understand the loss to MBS investors based on the mass prepay, but aren’t the rate at which these securities are being prepaid (especially for the higher coupons) being held artifically low based on current market conditions that make it more difficult to refi than it was when the MBS were purchased? So in short, are the investors in these securities doing better than they would relative to what would happen from a prepay standpoint in a normal market? Just thinking out loud here but it would seem that a mass refinancing may just get us back to normal from the standpoint of allowing people who would normally be able to refi (in a market without the current impediments) to do so.

Isn’t breaking a contract a violation of basic property rights? You are absolutely right that “investors and borrowers are parties to a set of contracts…” But that contract never contemplated a mass refi initiative for which the investor never agreed to or was compensated for. Have you considered where mortgage financing will be be offered by investors the day after such a blanket refinancing occurs? And what impact that will have on home prices? Oh, but worry not, it’s only going to happen once, right…

This paper does not establish that refinancing is a non-zero sum event. For example, while the foreign mortgage investors’losses may not affect U.S. consumption much they are still losses. The same is true for Fed and government mortgage holdings. In fact, refinancing is maximally zero-sum since it involves transaction costs. Instead, the authors really mean to argue that there is likely a fiscal stimulus associated with refinancing due to the differing marginal consumption propensities of investors and mortgagors. But a force majeure refinancing by the government in which various Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac covenants (including their charter covenants) are broken amounts to a special tax on mortgage investors for the benefit of mortgagors (and, of course, the refinancing agents who collect fees.)Imposing or reducing a tax on a particular asset class may sometimes make sense (e.g., municipal bonds, commercial real estate.)However, there are always costs. In the case of non-market driven refinancing we should expect one of the costs to be higher returns demanded by future mortgage investors to compensate them for the added risk of government intervention. More generally, if fiscal stimulus is what is wanted then other, much more productive avenues of attack are available. These include everything from temporary tax cuts for mortgagors to “deficit spending” to the proverbial helicopter drops of money. The refinancing approach has all the merits of theft over honest toil.

This is a great post, really laid out nicely and easy to understand by both layperson and economist alike. There is a piece here from the American about a potential “surprise” multi-trillion dollar refinancing the administration may be planning – http://blog.american.com/2012/01/january-surprise-is-obama-preparing-a-trillion-dollar-mass-refinancing-of-mortgages/. The author James Pethokoukis makes that same argument about that affect on MBS prices, although seems most concerned about how this could help Obama politically. Who knows if Pethokoukis is even correct about this – seems a bit farfetched – but at least reading Mr. Tracy’s piece it seems like the benefits of refinancing far outway the costs. Anyway, for any reading this post, check out the other piece for comparison.

You make a very convincing argument. One question: If we assume that one dollar of mortgage refinancing results in 50 cents worth of spending, what is the actual dollar amount of spending implied based on the number/amount of mortgages that would qualify under this plan?

The FED’s low/zero interest rate policy is having a devastating effect on the U.S. economy, after we net the positives and negatives. Why? The effects of this policy are quite asymmetric. Only those who need to borrow (and can qualify for a mortgage or other loan) are helped by the low rates. This is probably less than 20% of the populace. Many consumer interest rates, such as those for credit card debt, remain ridiculously high. On the lending side, almost everyone is being hurt; most people have a money market fund. bank account, brokerage account, CD, or some other investment vehicle, for which the return is being held close to zero, by FED policies.The net effect of the low/zero rate policies is a sharp decrease in consumer income and consumer spending.

Joshua, What you are forgetting to include is the loss to taxpayers from prepayments on any MBS that the Treasury/Fed/GSEs own. These mortgages conservatively are valued at 107 and a prepayment means the taxpayers only get 100 back. With the gov’t owning about $1.5 trillion in mortgages, a 7% loss equates to $105mm loss to the taxpayers. While this loss may not be seen in consumer spending, it is irresponsible for you to make your argument of less than a zero sum game without including this huge cost to us taxpayers.