Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz

Although the unemployment rate of workers with a college degree has remained well below average since the Great Recession, there is growing concern that college graduates are increasingly underemployed—that is, working in a job that does not require a college degree or the skills acquired through their chosen field of study. Our recent New York Fed staff report indicates that one important factor affecting the ability of workers to find jobs that match their skills is where they look for a job. In particular, we show that looking for a job in big cities, which have larger and thicker local labor markets (that is, bigger markets with many buyers and sellers), can give workers a better chance to find a job that fits their skills.

Theoretical research in urban economics suggests that the large and

thick local labor markets found in big cities can increase the likelihood of job matching and improve the quality of these matches. These benefits arise because big cities have more job openings and offer a wider variety of job opportunities that can potentially fit the skills of different workers. In addition, a larger and thicker local labor market makes it easier and less costly for workers to search for jobs.

Our research focuses on whether college graduates located in big cities are better able to find jobs that match the skills they’ve acquired through their college education. We utilize newly available census data that identify both an individual’s level of education and, for college graduates, undergraduate college major. We construct two measures of what we call job matching for those with a bachelor’s degree. Our first measure, which we refer to as college degree matching, determines whether an undergraduate degree holder is working in an occupation that requires at least a bachelor’s degree. Our second measure, which we call college major matching, gauges the quality of a job match by identifying whether a person is working in a job that corresponds to that person’s undergraduate major. For example, consider a college graduate who majored in Communications. If this person worked as a public relations manager, an occupation that both requires a college degree and relates directly to a Communications major, we would classify this person as matching along both measures. By contrast, if this person worked as a retail salesperson, he or she would be classified as not matching along either measure.

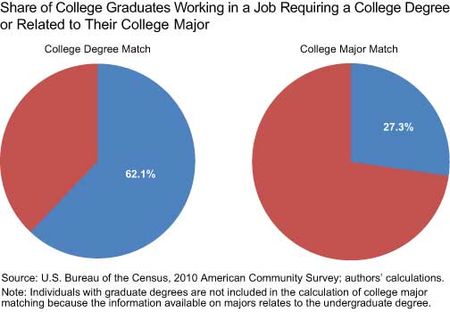

What percentage of college graduates match along these two dimensions? As the chart below shows, we find that close to two-thirds of college graduates in the labor force work in a job requiring a college degree, while a little more than a quarter work in a job that is directly related to their college major.

In our staff report, we estimated the relationship between the size and density of a metropolitan area and the probability of job matching to examine whether big cities help college graduates match into better jobs. Estimating these relationships turns out to be quite challenging because biases may result if either the workers or job opportunities in big cities are systematically more or less conducive to job matching. To address this difficulty, our analysis controlled for a wide array of worker characteristics, such as age, gender, marital status, and college major. We also controlled for characteristics of the metropolitan area in which these individuals were located, such as industry structure and differences in economic performance.

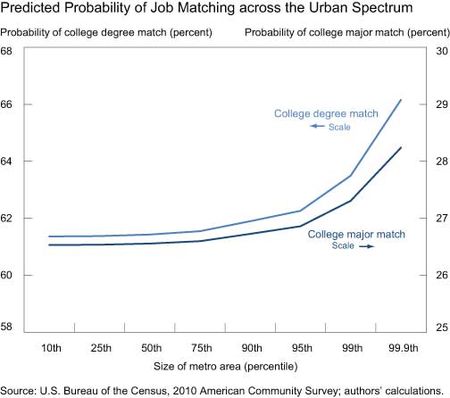

The chart below shows our estimates of the probability of job matching across the urban spectrum for each of our measures. The horizontal axis measures the size of a metropolitan area in terms of population and is marked in percentiles. (The correlation between metropolitan area size and density is quite high, so the results along either dimension are similar.)

To put these percentiles into perspective, St. Cloud, Minnesota, which has a population of about 190,000, is at the 25th percentile; while Chicago, with a population of more than 9 million, lies above the 95th percentile.

Our estimates suggest that both types of job matching are more likely in the larger and thicker local labor markets available in big cities, with job matching benefits concentrated at the top of the distribution. For example, the probability of a college graduate working in a job requiring a college degree increases from 61.1 percent to 64.5 percent when the population size of a metropolitan area increases from the 50th percentile to the 99.9th percentile. This implies that college degree matching is about 6 percent more likely in a place like New York City than in a place like Syracuse, New York. For the same movement across the urban spectrum, the probability of a college graduate working in a job related to his or her college major increases from 26.7 percent to 29.1 percent, implying that college major matching is about 9 percent more likely. Thus, the larger and thicker local labor markets of big cities appear to help college graduates find better jobs by increasing both the likelihood and the quality of a job match.

Given the expense of college and the potential difficulty faced by graduates in finding a job that utilizes the skills obtained through higher education, improving the chances of finding a good job is clearly important. Our work suggests that living in a big city can help.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jaison R. Abel is a senior economist in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for your comments; we’re glad you enjoyed the post. As the first comment suggests, there are a number of challenging estimation issues involved with this analysis, and, as our Staff Report details, we do our best to address them. While it is true that big cities have a higher cost of living, it is also true that workers tend to earn higher wages in these places, which typically compensates for the added costs. An important issue related to your comment is what economists refer to as “sorting”—that is, the best and brightest tend to locate in big cities, in part because of the higher cost of living. We address this issue by controlling for a wide array of individual worker characteristics that may influence job matching. Importantly, because of the data we utilize, we are able to account for each person’s college major, which provides a more complete way to control for differences in skill than has been available in previous studies of this nature. Regarding the comment about the comparison between New York City and Syracuse, keep in mind that the 6 percent increase we estimate is related to only the larger size of New York City (and the labor market benefits that result) compared to a place like Syracuse. That is, our analysis controls for other factors that might influence job matching among college graduates, such as differences in worker characteristics and the economic structure of each metropolitan area. So, the actual difference in the probability of working in a job related to your college education in New York City compared to Syracuse may well be larger than 6 percent, but that would be because of other differences between these places.

Love the Syracuse example. This is bullish for Syracuse with only a 6% increase in applicant chances for degree required work versus NYC. Was under the belief the differential was greater would would suspect high variability by the degree types themselves.

This is a good research note and makes total sense. However, the main question is how do you address the endogeneity problem – that in order to afford living in a big city you need to have a job offer in that city before hand. There may be two groups of people who can benefit from a higher probability of a job that matches their skills: those college students who grew up in a big city and are able to go back to their parents’ home and then look for a job, and those with a more wealthy background who may afford a few months of living in a big city before finding a job that matches their skills. How do you address the rest of the population who can’t afford to live in a big city without any financial support?