The recent financial crisis underscored the importance of understanding how liquidity conditions for banks (or other financial institutions) influence the banks’ lending to domestic and foreign customers. Our recent research examines the domestic and international lending responses to liquidity risks across different types of large U.S. banks before, during, and after the global financial crisis. The analysis compares large global U.S. banks—that is, those that have offices in foreign countries and are able to move liquidity from affiliates across borders—with large domestic U.S. banks, which have to rely on financing raised in capital markets and from depositors to extend credit and issue loans. One key result of our study, detailed below, is that the internal liquidity management by global banks has, on average, mitigated the effects of aggregate liquidity shocks on domestic lending by these banks.

Possible Bank Responses to Liquidity Risks

Large U.S.-based banks can react to aggregate liquidity shocks by adjusting their domestic lending, their cross-border lending (for example, interbank loans or claims on other counterparties), or their internal lending and borrowing (with affiliates), or potentially make other balance sheet adjustments. The reaction to aggregate liquidity conditions could depend, importantly, on the composition and strength of each bank’s balance sheet. For example, if a bank has stable deposit funding or maintains more liquid assets on its balance sheet, its lending might be less affected by aggregate liquidity shocks.

There also might be different responses to liquidity risk by U.S. banks that are domestically oriented compared with banks that are more global. Because these two types of banks have very different business models, the channels and magnitude of transmission of liquidity risks into bank lending may differ significantly. Small domestic banks have relatively strong lending responses to liquidity risks (Kashyap and Stein [2000]; Cornett, McNutt, Strahan, and Tehranian [2011]). By contrast, banks with foreign affiliates, particularly large banks, actively move funds across their organizations to offset such risks, and potentially insulate lending in their home markets (Cetorelli and Goldberg 2012). However, these same banks may decrease lending abroad as they move liquidity into their home country. For both types of banks, changes in aggregate private liquidity are likely to influence lending differently in crisis than in normal periods, in part because of the availability of and willingness to use official sector liquidity facilities in periods of aggregate liquidity stress. When banks have access to central bank liquidity facilities priced at terms below private market rates, this might relax the constraints imposed by the composition of banks’ balance sheets on their access to external funding, leading to a different relationship between those balance sheet characteristics and the banks’ lending (Buch and Goldberg 2014).

The Framework for Studying How Liquidity Risks Affect Bank Lending

Two methodological building blocks underlie the empirical strategy followed in our study. The first is Cornett, McNutt, Strahan, and Tehranian (2011), who examine the role of bank balance sheet composition in explaining how U.S. banks’ lending reacts to changes in aggregate liquidity conditions. They posit that banks are more sensitive to aggregate liquidity conditions depending on the market liquidity of their assets, the use of stable core deposits, their capital ratios, and their funding liquidity exposure stemming from loan commitments (or new loan originations via drawdowns).

The second building block is Buch and Goldberg (2014), who integrate into this framework considerations specific to global banks, and also show the potential consequences of bank access to official sector liquidity facilities. For the global banks, strategies for liquidity management can play an important role and these strategies are reflected by the use of internal funding transactions between the head office and its domestic and foreign affiliates. The balance sheet characteristic that reflects this feature of global banks is their reported use of “net due to” or “net due from” their affiliated institutions, which refers to their borrowing from or lending to other parts of the bank holding company.

We focus on a sample of U.S. banks, using data from 2006 through 2012. We concentrate only on larger U.S. banks (with more than $10 billion in assets) and we distinguish between banks with claims booked through foreign affiliates (global banks) and those without such claims (domestic banks). These two groups of banks can lend to both domestic and foreign borrowers. In the case of global banks, lending to foreign residents can be arranged either through cross-border transactions or through their foreign affiliates (which take the form of a subsidiary or branch).

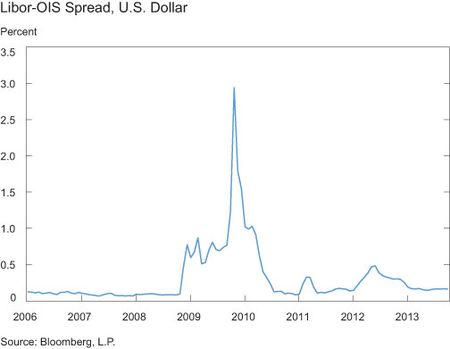

Our measures of aggregate liquidity strains in financial markets are the rates that banks use when lending to one another, known as interbank spreads (such as the London interbank offered rate over the overnight indexed swap, known as the Libor-OIS spread). As shown in the chart below, these rates spiked during the financial crisis as U.S. and European banks became less willing to lend to one another and liquidity dried up, especially at maturities beyond a few days.

Our tests take into account banks’ use of official sources of liquidity. In 2008, the Federal Reserve announced a number of extraordinary official liquidity facilities to relieve the strains in U.S. financial markets during the crisis. Because the cost of funds at official facilities was at times lower than private market rates, we allow for a different response of individual banks to aggregate prices of liquidity during periods when the bank taps official sector facilities. Thus, our analysis incorporates information by bank on when institutions accessed the Term Auction Facility (TAF) and discount window, and incorporates the balance sheet characteristics of these same financial institutions as well as their global nature to understand differences in the transmission of liquidity risk to loan and credit growth.

What Matters for the Effects of Liquidity Risk

We find that elevated levels of liquidity risk, as measured by interbank spreads, have significant, but different, effects on lending growth across different types of large U.S. banks. The balance sheet characteristics that matter for these different responses depend on whether the banks are global. For large, non-global banks, the key balance sheet characteristic that explains the impact of a funding shock on loan growth is the share of core deposits in bank funding. The economic impact of having more core deposit funding during a crisis is large: a bank with core deposits representing roughly 76 percent of its total liabilities (in the 75th percentile of the in-sample distribution for this ratio) would lend $211 million more in domestic commercial and industrial (C&I) loans in a given quarter (about 9 percent of domestic C&I loans of the median bank) than a bank with a core deposit share of liabilities of 58 percent (in the 25th percentile of the distribution), after a 100-basis-point increase in the Libor-OIS spread.

By contrast, we find that for global banks, the impact of liquidity shocks depends more on their liquidity management strategies, as reflected in outstanding internal borrowing or lending between the head office and the rest of the organization. Net internal borrowing (liabilities from the head office to its affiliates minus claims by the head office on those affiliates) increases in periods with heightened liquidity risk for the U.S. banks that have higher outstanding unused commitments and lower Tier 1 capital ratios. This higher net internal borrowing is associated with relatively more growth in domestic lending, foreign lending, credit, and cross-border lending. The economic magnitude of the effect of net internal borrowing on domestic C&I loans is also large: a bank that finances 6.6 percent of the head office liabilities (in the 75th percentile) with internal net borrowings would lend $800 million (or 5 percent of domestic C&I lending of the median bank) more in a given quarter than a bank that only finances 1.2 percent of its liabilities (in the 25th percentile) with these funds, after a 100-basis-point increase in the Libor-OIS spread.

We find that cross-border lending and internal borrowing and lending tend to be more volatile than domestic lending and lending conducted through U.S. bank affiliate offices abroad. The model we estimate explains some of the observed changes in domestic loan growth, as well as changes in internal capital market positions, but doesn’t capture as much of the volatility in cross-border lending growth of U.S. banks. At the same time, cross-border lending appears to be sensitive to more bank balance sheet characteristics than any of the other forms of lending. Regardless of the form of lending, the role of bank balance sheets is diminished when liquidity risks increase substantially and the banks access official sector liquidity. Thus, official sector liquidity moderates the effects of private sector liquidity risk on both domestic lending and cross-border flows.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Ricardo Correa is a section chief in the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System’s International Finance Division.

Linda S. Goldberg is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Tara Rice is a section chief in the Board of Governors’ International Finance Division.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics