Correction: This post was updated on May 8 to correct the book title and spelling of the author’s name in the fifth paragraph. We regret the error.

President Andrew Jackson was a “hard money” man. He saw specie—that is, gold and silver—as real money, and considered paper money a suspicious store of value fabricated by corrupt bankers. So Jackson issued a decree that purchases of government land could only be made with gold or silver. And just as much as Jackson loved hard money, he despised the elites running the banking system, so he embarked on a crusade to abolish the Second Bank of the United States (the Bank). Both of these efforts by Jackson boosted the demand for specie and revealed the soft spots in an economy based on hard money. In this edition of Crisis Chronicles, we show how the heightened demand for specie ultimately led to the Panic of 1837, resulting in a credit crunch that pushed the economy into a depression that lasted until 1843.

Jackson’s Stand “Against Any Prostitution of Our Government”

From the first day of his presidency, Jackson was committed to eliminating the Bank, which was a private bank with some shares owned by the federal government. The Bank was the sole fiscal agent for the U.S. Treasury and therefore could create credit across the country by pushing out or holding onto government specie. It also played a major role by issuing a national currency, backed by the Treasury’s deposits, that was more credible than the currency issued by the banks. In addition, the Bank could limit the creation of paper currency by requiring the banks that were over-issuing notes to hand over specie when their banknotes were used to pay taxes. The risk of having to give back specie limited the size of banks, so many agreed with Jackson that the economy would be better off without the Bank.

When he refused to extend the Bank’s charter in 1832, Jackson proclaimed that “We can at least take a stand against all new grants of monopolies and exclusive privileges, against any prostitution of our Government for the advancement of the few at the expense of the many.” Hammond, in Banks and Politics in America (1957, p 349), opined that “Jackson was extraordinarily effective in combat. He combined the simple agrarian principles of political economy absorbed at his mother’s knee with the most up-to-date doctrine of laissez faire.”

Extravagant Schemes and Fantastic Operations

In the run-up to the Panic, the banking system was busy financing the construction of railroads and canals, offering credit to those buying government lands and those expanding agricultural and manufacturing ventures. The government was making so much money from land sales and the Tariff of 1833 that its debt was paid off in 1835. In his re-election campaign, Jackson promised that additional revenues would be sent to the states, and the anticipation of such funds led many states to initiate big infrastructure investments that made their finances vulnerable when the 1837 crisis hit.

McGrane, in his book, The Panic of 1837 (1924, p. 42), wrote, “The questionable banking practices and extravagant internal improvement schemes of the East were duplicated by similar fantastic operations in the West and South. The universal prosperity of the nation led individuals and states to expand credit too rapidly, now that the restraining influence of the United States Bank had been removed.” The demise of the Bank required that all of the Bank’s specie be distributed around the country, further enabling banks to expand their lending, and ended any oversight of their banknote issuance. In early 1837, a prudent person might have thought that gold and silver looked like a wise portfolio choice.

Jackson further pushed up demand for specie with the Specie Circular, an executive order signed in 1836 that required that specie, and not banknotes, be used to buy government lands. He did this to limit the amount of paper money received by the government and because he thought there was a bubble in land prices. He reasoned that requiring payment in gold and silver would pop the bubble.

This aggressive push to wean the economy off of paper currency—and onto hard money—strained the banking system. Demand for specie by customers in New York City exceeded supply, and, on May 9, 1837, banks there responded by refusing specie withdrawal. The suspension of convertibility in the nation’s financial center caused panic that quickly spread to the rest of the country. Banks, looking to replenish the specie in their vaults, refused to make new loans and called in existing loans, triggering a collapse of credit and a severe and prolonged decline in production and employment across the country.

Post-Crisis: Two Tendencies in Banking

The crisis set the next stage for banking. Helderman, in National and State Banks (1931, p.9), wrote, “Under the lash of economic distress, two clear tendencies emerged: one, a reform movement; the other, a sharp anti-bank reaction. The reform movement first evolved into a program in New York where in 1838 the free-bank system was created . . . The other result was to intensify the hard-money ideas of the day, leading to a movement in the West to abolish banks of issue. Absurd as it may seem today, the movement was based on a theory shared by many sober men of the time.” Free banking allowed individuals to set up private banks without the approval of state legislators, although with the requirement that they hold state bonds. These efforts reflected a desire to increase the creation of credit and a dislike of governments granting special privileges.

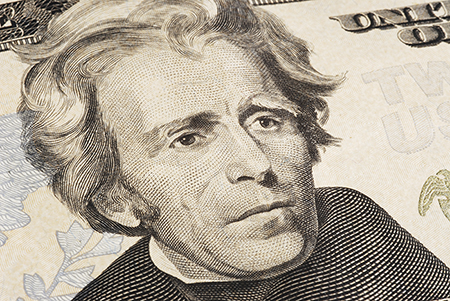

Women on Currency

In a bit of modern irony, there is a movement today to replace Jackson’s portrait on the twenty-dollar bill. The WomenOn20s organization is hosting an online referendum to allow the public to vote for their favorite female candidate, and it plans to petition President Obama to direct the Secretary of the Treasury, who oversees currency design, to make the change. Images of women once dominated the design of bank-issued currency, as Stephen Mihm explains. Portraits ranged from ethereal representations of justice, goddesses, and mythology, to anonymous working women, to real women such as Pocahontas, Martha Washington, and Swedish opera star Jenny Lind, “the Beyoncé of her day,” according to Mimh.

One argument for removing Jackson that is made on the WomenOn20s website is that, because Jackson was a fierce opponent of the central banking system and favored hard money over paper currency, he’s an odd choice to be represented on Federal Reserve notes in the first place. So, should Jackson be replaced on the twenty-dollar bill? And if so, with whom? Tell us what you think.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

James Narron is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s Cash Product Office.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you, Farrar, for your comment. You can find some pushback to Temin’s view in Peter L. Rousseau’s, “Jacksonian Monetary Policy, Specie Flows, and the Panic of 1837,” Journal of Economic History (2002).

Jackson’s attack on the 2nd Bank of the US was not consistent with his preference for specie. His moves resulted in issuance of paper money by nearly 1000 banks (at any given time) covering the full spectrum from bogus to sound. He pulled the government deposits and business from the 2nd Bank and gave them to his pet banks that had strong connections to his administration. The 2nd Bank managed the currency about as well as the Federal Reserve has (faint praise, I’ll admit), but the wildcat banks, currency dealers, and lack of legal tender paper money that followed its demise mocked a makery of money.

I was under the impression that Peter Temin in his thoroughly researched, and well argued, The Jackson Economy (1969), had largely cleared Jackson of blame for the 1837 recession. It seems to me you have simply repeated the classical story of this recession, which as Temin showed is not supported by the facts, The theories that you reiterate here were long accepted as plausible and probable causes of the recession, and they do make a better story. It is unfortunate, however, that a prestigious blog like this should risk perpetuating a historical myth, without even mentioning Temin’s thorough scholarship which debunked it. I hope you will issue a correction, or at least a clarification.

This is a great post that summarizes some of the most important details of this important period in American economic history, thanks. The bit at the end about previous women on the currency was a nice bonus. My vote for the new $20 is Elanor Roosevelt.

Jaime, thank you for pointing out the error. We have corrected the post.

I vote to remove him and I like the idea of replacing him with a woman, specifically Sacagawea. I like the irony of replacing Andrew Jackson with a Native American since he was responsible for the ” Trail of Tears”.

During the height of the recent financial crisis I often mused that maybe the world would have been better off had it followed Jackson’s advice–all financial transactions being cash on the barrelhead, with the cash consisting of specie. By the way, Jackson’s close follower, Thomas Hart Benton (an ancestor–not the painter!), was nicknamed “Old Bullion,” reflecting his obsession with this topic.

“Magrane, in his book, The Panic of 1937 (1924, p. 42), wrote, …” Should 1937 be changed to 1837?