Debt and its performance play a critical role in economic development. The enormous increase in mortgage debt that took place during the run-up to the 2007 financial crisis and the contribution of that debt to the crisis underscore the importance of household debt to financial stability and economic growth. While we regularly report on household debt at the national level and for selected states in our Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, we have not reported separately on Puerto Rico. This post introduces metrics on household debt in Puerto Rico, which we plan to update regularly. Like our other reports on household debt, this analysis uses our FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel, which is based on anonymized credit data from Equifax. We also take a look at some data for Puerto Rico’s banking sector to complete the picture of household debt for the Commonwealth.

The View from the (Household) Borrowers

Not surprisingly, the most prominent feature in the evolution of national household debt is the pronounced turnaround in debt that began in 2008. Between 1999 and 2007, we saw substantial increases in household debt each year, driven especially by mortgage debt. Then, starting in the third quarter of 2008, household debt began to contract, led again by mortgages. This period of household deleveraging lasted for about five years and was associated with a sharp reduction in consumption and a deep recession. In 2013, debt began to grow slowly and by mid-2014 it was clear that the national deleveraging period had concluded.

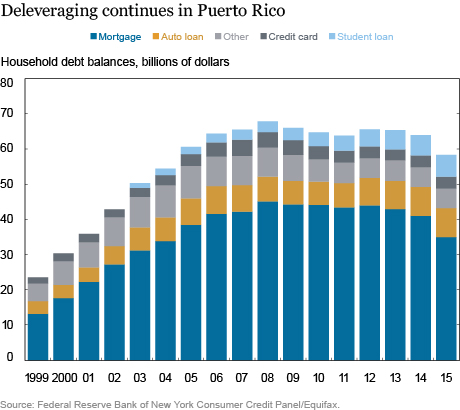

The Puerto Rico data for household debt, which comprise a sample of over 125,000 anonymized credit reports for residents of the Island, bear some striking similarities to the national data. Debt in Puerto Rico peaked in the second quarter of 2008, just as it did on the mainland. In addition, aggregate debt on the Island declined 13 percent from its 2008 peak to 2015, while the comparable peak-to-trough figure for the nation as a whole was 12 percent. However, a crucial difference between Puerto Rico and the mainland is that in spite of a slight bounce-back in 2012, household debt in Puerto Rico continues to fall, as seen in the chart below. At this point, the nation as a whole has retraced three quarters of its decline and debt today is just 3 percent below its previous peak. Puerto Rico’s household debt is still 12 percent below its second-quarter 2008 peak, and debt at the end of 2015 was lower than it was a decade earlier.

As can also be seen in the chart, household debt in Puerto Rico is dominated by mortgages, which make up 60 percent of total household debt in the Commonwealth compared with 69 percent in the nation as a whole. The shares of student debt and credit card debt in Puerto Rico are comparable to the mainland. Notably, auto debt has a bigger share of the Puerto Rican debt picture than on the mainland, at 14 percent (compared with 9 percent for the United States as a whole). We don’t observe any home equity lines of credit in Puerto Rico.

There are differences in both participation (that is, the share of borrowers with a particular debt product) and in the amounts that are owed. Participation in consumer debt markets is lower in Puerto Rico than in the nation for auto loans, credit cards, mortgages, and student loans. And the average balances on accounts are lower, with the exception of auto loan balances. Mortgage balances average $70,000 in Puerto Rico compared with $122,000 on the mainland, credit cards average $4,300 compared with $5,100 on the mainland, and student loans equate to $20,000 per borrower, compared with $27,000 on the mainland. Auto loans are the big exception to this pattern—the average auto loan balance in Puerto Rico is $1,300 higher than on the mainland, at $14,800.

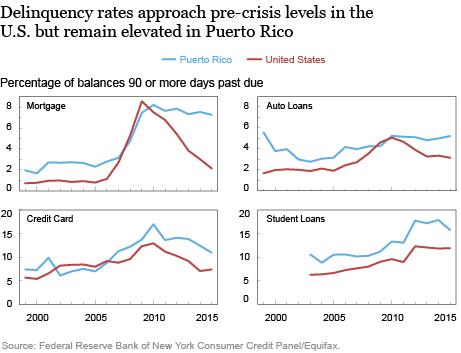

Another major characteristic of indebtedness is performance: Are borrowers able to keep up with their payments? In the United States, a dramatic run-up in mortgage delinquencies (seen in the red line of the upper left chart below) was a major factor leading to the financial crisis. Since their peak in 2009, however, U.S. mortgage delinquencies have come down sharply. Not so for Puerto Rico, where the serious delinquency rate on mortgages has remained stubbornly high, at 7 percent compared with 8 percent at the 2010 peak. Serious delinquency rates on other forms of debt in Puerto Rico also remain well above those on the mainland.

Most of the explanation for this differing performance of debt in Puerto Rico surely lies with the Island’s poor economic performance over the last decade, which has been widely documented. An additional factor that is apparent in our data is the riskiness of the outstanding debts. One measure of this is the share of the outstanding stock of debt that is owed by borrowers with subprime (below 620) credit scores (we use Equifax Riskscores). As we’ve noted before, subprime lending is an important feature of the national auto finance market, and this is also true in Puerto Rico, where the subprime share is roughly a quarter, close to the mainland figure. The differences are larger when it comes to mortgages, with the Puerto Rican data for 2015 showing a significantly higher share of subprime loans, at around 20 percent compared with just 8 percent for the United States as a whole. Subprime shares have come down significantly since 2009 for both Puerto Rico and the nation for both auto loans and mortgages.

The View from the Lenders

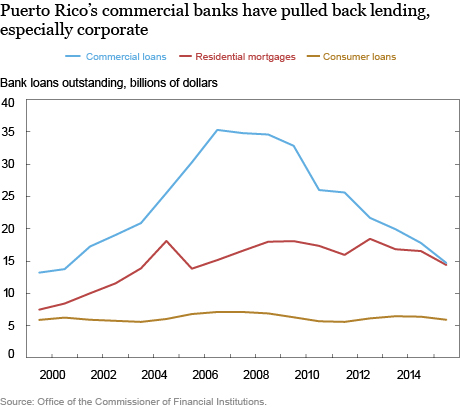

The FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel offers a great deal of detail on household debts and their performance, but it is interesting to expand the picture by looking at Puerto Rico’s private commercial banks. The chart below, based on data from Puerto Rico’s banking regulator, shows the banking sector’s loan portfolio over time. Residential mortgage loans have declined since 2008, a trend also reflected to some degree in the household data. The two data sources differ in many ways, including the fact that the bank data show only assets on balance sheet and exclude securitized loans. Nonetheless, the serious mortgage delinquency rate (ninety or more days past due) recorded in the banking data matches the credit bureau data almost exactly. Overall, banks’ household loan balances have declined to less than 30 percent of GNP from 40 percent in 2008. What is more striking, however, is the contraction of banks’ commercial loan portfolios after a run-up in construction and commercial real estate lending. The stock of outstanding corporate debt held by Puerto Rican banks fell from $35 billion in 2006 to less than $15 billion by the end of 2015, a decline of nearly 60 percent. By contrast, loans on the books of the financial sector in the mainland declined sharply between 2008 and 2012 but have been increasing since and now approach pre-crisis levels.

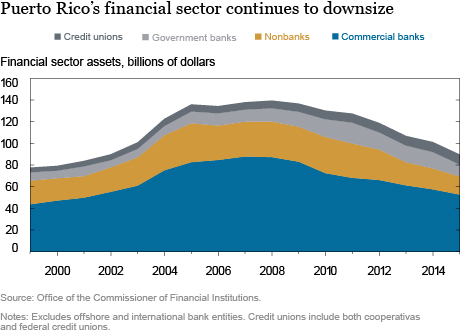

This decline in commercial lending, along with considerable consolidation following the failure and subsequent acquisition of three commercial banks in 2010 and one in 2015, is a major source of the downsizing of the Commonwealth’s financial sector, as shown in our final chart, below. While lending to households by credit unions has increased since 2006, bank and nonbank lending (including by mortgage finance companies) has declined more significantly, leading to a financial sector that is now about the same size in dollar terms as it was in 2002. Relative to the size of the economy, however, financial sector assets now stand at 125 percent of GNP, down from 200 percent of GNP in 2002.

Conclusion

Whether we measure it from the perspective of lenders or borrowers, Puerto Rico’s financial sector seems to be shrinking. Elements of both supply and demand are probably at work here, since in an environment of diminished economic growth and elevated delinquencies both lenders and borrowers are likely to restrict financing activity, including the extension of household credit. These effects may be amplified by the contracting population. The high level of consumer delinquencies that we see in the Consumer Credit Panel indicates that borrowers in Puerto Rico remain stressed in a way that has become far less common in the nation as a whole. The resumption of economic growth will both result from and be a cause of improvements in the credit outlook. We will continue to monitor and report on the household data in an effort to keep the public informed about those developments.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Meta Brown is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is an officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is the administrator of the Center for Microeconomic Data in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Magali Solimano is a financial analyst in the Bank’s Integrated Policy Analysis Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Meta Brown, Andrew F. Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Joelle Scally, Magali Solimano, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “Puerto Rico’s Evolving Household Debts,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), August 12, 2016, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/08/puerto-ricos-evolving-household-debts.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics