Erica L. Groshen

In this post, I show that despite the depth of the Great Recession, U.S. employers did not use temporary layoffs much to cut costs. Just as they did during the previous two recessions, when firms laid workers off, they usually severed ties completely. This prevalence of permanent layoffs during the recession could slow the employment rebound over the coming months. It also raises questions about why the behavior of employers during recessions has changed.

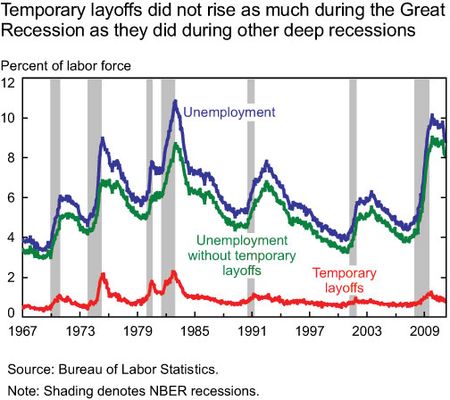

The chart below shows that the Great Recession is the third downturn in a row in which temporary layoffs have not spiked noticeably. The new cyclical pattern for temporary layoffs is quite distinct from the sharp peaks in the recessions of 1975, 1979, and 1981; each of those saw a huge surge in temporary layoffs. By contrast, temporary layoffs showed smaller, less abrupt increases during more recent recessions. To provide contrast and complete the picture, the chart’s top line shows the unemployment rate while the middle line shows the share of the labor force that is unemployed for a reason other than a temporary layoff (such as a permanent layoff, quit, or entry).

You may recall seeing a graph like this before. Using a similar chart, Simon Potter and I noted a smaller role of temporary layoffs during the 2001 recession in a 2003 New York Fed Current Issues in Economics and Finance article.

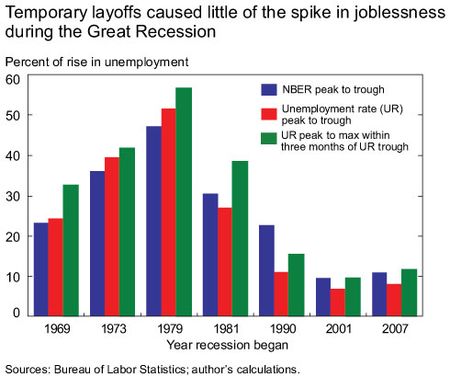

To quantify the declining use of temporary layoffs during recessions, I calculate in the next chart the share of the total rise in unemployment attributable to temporary layoffs in the seven recessions since 1969.

During the last three downturns, temporary layoffs clearly played a much smaller role in the total rise in joblessness. I show three different bars because the beginnings and ends of recessions can be dated in different ways: official National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) dates, unemployment rate peaks and troughs, and temporary layoff troughs close to unemployment rate troughs. Any way you measure it, temporary layoffs accounted for much less of the peak-to-trough increase in joblessness during the 2007 recession than they did in downturns before 1990.

In our Current Issues article on the 2001 recession, Simon Potter and I offer two explanations for the switch away from temporary layoffs. The first focuses on modern personnel practices, such as lean staffing. Here, firms use recessions as opportunities to cull their workforces, close inefficient facilities, or make other fundamental changes. Rather than just “weathering the storm,” they try to emerge stronger. The second explanation notes that shallow, short recessions may have less cyclical “collateral damage.” That is, the impact of a mild recession may be highly concentrated in firms and industries that need to change, with little impact on fundamentally healthy firms or industries. If healthy employers prefer temporary layoffs (because they want their workers back when conditions improve), then a mild, short recession would lead to proportionally fewer temporary layoffs.

In the 2001 recession, the new personnel practices were prevalent, but the downturn was not deep or long. So, in our article, we couldn’t tell which explanation was correct. However, the fact that the severe Great Recession did not cause a big spike in temporary layoffs suggests that new behavior patterns of employers are likely to be an important explanation.

What does this mean for the labor market during the recovery? My first chart shows that during the 1975, 1979, and 1981 recessions, temporary layoffs reversed just as dramatically as they rose—and more quickly than the rest of unemployment fell. A comparison of the top two lines of that chart suggests that a downturn with a small share of temporary layoffs—like the Great Recession—is likely to return to full employment slowly after the official trough.

Related Questions

- Does a predominance of permanent layoffs mean that stimulative policy will be ineffective in helping employment to rebound? No. In fact, just the opposite is possible—countercyclical stimulative monetary or fiscal policy may be particularly important to improve confidence and incentives for firms to expand again when most of the jobs created must be new hires.

- How do temporary and permanent layoffs differ? When a worker is on temporary layoff, the employee expects a recall within six months. The worker’s personnel file remains open. Then, when demand returns, the worker can be back on the job, and productive, quite rapidly. In contrast to practices for new hires, there is no need for a search, pre-employment screening, training, orientation, etc. (Note: People who don’t expect a recall within six months are not classified as on temporary layoff; they are counted as unemployed if they have searched for work within the past month.) These definitions are used in the monthly Current Population Survey.

- Have employers stopped using temporary layoffs entirely? No. Temporary layoffs continue to be used for seasonal cuts (such as summers for ski resorts) or for idiosyncratic reasons (such as after a fire or natural disaster). And many employers still use temporary layoffs during recessions, just proportionally less than before. The bottom line of my first chart shows that the share of the workforce on temporary layoff during expansions has remained remarkably stable since 1967.

- Does declining unionization explain the fall in cyclical temporary layoffs? Collective bargaining agreements often specify a preference for temporary over permanent layoffs, and dictate how layoffs and recalls will be conducted. Thus, shrinking union representation since the 1970s may have contributed to the decline in cyclical temporary layoffs, but it is not clear why we would see such a rapid drop-off, mostly during the 1980s, if this were the only factor. Many cyclical industries, particularly durable goods manufacturing and construction, are still fairly highly unionized. Readers with insight into the role of unionization in the decline in cyclical temporary layoffs are encouraged to comment on this post.

- Is this all about employers avoiding a higher experience rating for unemployment insurance (UI)? The experience rating (whereby employers pay more for unemployment insurance if they have a history of longer or more frequent layoffs) has been a part of UI since its inception. Both forms of layoff affect an employer’s experience rating, so there is no clear change in UI experience rating to point to as an explanation during the 1980s and 1990s.

- Are layoffs the only way for employers to adjust their workforces during recessions? No. Employers can also cut hours, contract workers, business services, or temporary help.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thanks so much for these observations. They suggest two complementary elements to employers’ changed behavior: 1. Being selective about whom they lay off and expecting to hire more skilled or productive workers in their place 2. Making more fundamental or staffing changes that might damage morale in better times, such as a smaller labor force, a change in workforce skill set, outsourcing, etc. Both would certainly contribute to the patterns we see. Thanks again.

One sense I have from talking to HR professionals is that there is increasing use of performance criteria to determine who stays and who goes. This would be quite consistent with a decline in temporary layoffs – companies would rather hire new workers than call back those who have been let go because they have been identified as low performers. A related perspective from some in HR is that the recession provided an “opportunity” for companies to reduce their numbers. The idea here is that companies finding themselves with workers who are relatively low performers, or who do not have skills that are well matched to the organization’s future plans, have used the downturn as a sort of cover to engage in cuts that would be more difficult to implement in good times. Again, if this is the case, you wouldn’t expect such layoffs to be temporary.