The tri-party repo market is one in which large U.S. securities firms and bank securities affiliates (dealers) finance much of their fixed-income securities inventories. A New York Fed white paper and the Financial System Oversight Council annual report have highlighted the risks to financial stability arising from the current infrastructure of this market. The Tri-Party Repo Infrastructure Reform Task Force (Task Force), an industry group sponsored by the New York Fed, has been working on reforms that would address some of these concerns. Unfortunately, a key aspect of the reforms—capped and committed clearing bank credit—has been delayed. In this post, I describe the remaining risks created by this delay.

The Unwind Defined

The centerpiece of the current reform effort is the elimination of the wholesale daily unwind of tri-party repos, on both maturing and continuing term trades. The unwind consists of an extension of credit to a dealer by its clearing bank to facilitate the settlement of the dealer’s repos (for more details, see this New York Fed staff report.) The clearing banks return cash to cash investors and collateral to dealers each day and, in the interim, extend credit to dealers against their entire tri-party repo book. This unwind temporarily transfers the risk of a dealer’s default from cash investors to the clearing bank. When new repos are settled and continuing term trades are re-collateralized, the exposure to the dealer is transferred back from the clearing bank to cash investors (including new investors).

Why Eliminate the Unwind?

In a recent blog post, I argued that eliminating the wholesale unwind of tri-party repos could reduce fragility in that market. The delays in the reforms, however, leave the market just as vulnerable to the risk that a clearing bank might refuse to unwind a dealer’s trades as it was during the recent financial crisis. If a clearing bank refused to unwind a dealer’s repos, the dealer would almost certainly be forced into bankruptcy, because the dealer would probably not be able to attract new funding that day. That event could create instability in the tri-party repo market that could in turn spill over into other markets. While this risk is not new, its continued existence remains a serious concern.

Clearing bank exposure to a single dealer is uncapped and can routinely exceed $100 billion. In the event of an intraday dealer default, a clearing bank would have to take the dealer’s entire portfolio of securities being financed via tri-party repo onto its balance sheet. This could affect the financial health of the clearing bank because its intraday exposures loom large relative to its capital. Liquidating such a large portfolio would take time, and the clearing bank would run the risk that the market value of the collateral would be less than the amount owed to the clearing bank.

The handoff of exposure between the cash investors and the clearing banks could also lead to perverse dynamics, in part because clearing bank credit is not committed. For example, suppose that cash investors become concerned that a clearing bank may refuse to unwind the repos of a certain dealer. Because that would force the dealer into default, cash investors would be reluctant to finance the dealer the day before. The inability of the dealer to obtain financing from cash investors may accelerate the dealer’s default. Similarly, a clearing bank would be reluctant to unwind the repos of a dealer if it expected that the dealer may not be able to obtain financing from cash investors at the end of the day. Such expectations would be self-fulfilling.

The Task Force has focused its efforts on eliminating the gap between the unwind of old repos and settlement or re-winds of new and continuing trades. The objectives are to settle new and expiring repos simultaneously and to unwind only maturing trades, as both measures dramatically reduce the need for clearing bank credit. Implementing the necessary changes has proved challenging, however, resulting in delays to the Task Force’s original timeline as described in its July 6 Progress Report.

For the foreseeable future, both clearing banks will be performing a wholesale unwind of each dealers’ entire tri-party repo book. At the time of the unwind, the clearing bank may be uncertain whether the dealer’s end-of-day collateral meets the terms of the new trades. Indeed, the dealer’s assets are disseminated across different custodial systems, and normal funding patterns could be disrupted as a dealer comes under stress.

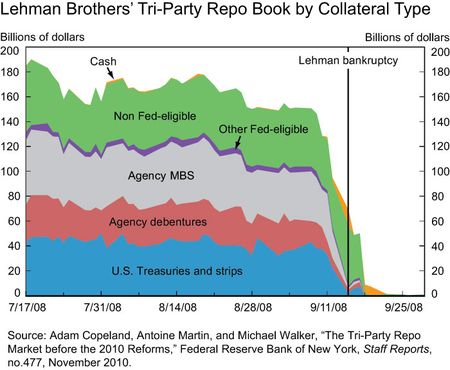

If the dealer does not ultimately have adequate collateral to meet the terms of its new trades, the clearing bank could not allocate collateral to these trades, and it might be the only institution in a position to fund the troubled dealer’s collateral. As we saw in 2008, this situation could arise without much warning, and the amount of clearing bank credit needed could be material for several reasons. First, a troubled dealer is likely to quickly lose access to term funding, so that an increasing share of its tri-party repo book would mature overnight. Second, cash investors who continue to fund the dealer are likely to demand higher quality collateral. Third, a troubled dealer is more likely to be able to sell its most liquid assets, causing the average quality of its remaining pool of collateral to deteriorate. Under these conditions, it would be difficult for the clearing bank to determine accurately whether it should extend credit and, in an uncertain environment, it might choose not to do so even in cases in which the dealer is still solvent. Some of these dynamics were at play in the days before Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, as illustrated below.

This uncertainty could lead to two potential errors, each with undesirable consequences. One error would be for the clearing bank to refuse to lend when the dealer actually does have adequate collateral. This would force the troubled dealer into default and bankruptcy. Fire sales and a retreat from funding of otherwise healthy dealers could also potentially result, given the pressures cash investors are likely to face. For example, money market mutual funds—still a predominant source of funding in the tri-party repo market—would be pressured to sell assets that they can accept as collateral but are not permitted to own outright.

The second error would be for the clearing bank to lend when the dealer actually does not have collateral. In this case, it is unlikely that the dealer would be able to attract new cash investors the following day, and the clearing bank would end up owning any collateral it financed. This would likely be the dealer’s lowest quality collateral.

Conclusion

The wholesale unwind of tri-party repos is a serious weakness of the market, one with potentially systemic consequences. The risks just described will be greatly reduced if the clearing banks can simultaneously settle a dealer’s new and expiring repos. Simultaneous settlement will dramatically reduce the need for clearing bank credit, allowing such credit to be capped and committed. This objective is the centerpiece of the current reforms, and the Task Force should not rest until it has been fully met.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics