Dafna Avraham, Patricia Selvaggi, and James Vickery

When market observers talk about a “bank,” they are generally not referring to a single legal entity. Instead, large domestic banking organizations are almost always organized according to a bank holding company (BHC) structure, in which a U.S. parent holding company controls up to several thousand separate subsidiaries. This hierarchy of controlled entities generally includes domestic commercial banks primarily focused on lending and deposit-taking as well as a range of nonbanking and foreign firms engaged in a diverse set of business activities, such as securities dealing and underwriting, insurance, real estate, private equity, leasing and trust services, asset management, and so on. In this post, we present some results of our article and contribution to the special EPR banking volume, “A Structural View of U.S. Bank Holding Companies,” which uses public regulatory data to document trends and stylized facts about the size, organizational complexity, and scope of large U.S. BHCs.

Understanding the organizational structure of BHCs is crucial from the perspective of creditors and regulators alike, since the risk of financial distress and the availability of public backstops (for example, deposit insurance) differ substantially across different entities within a BHC. To protect depositors and core banking activities from nonbanking losses, regulations commit BHCs to act as a “source of strength” for their commercial banking subsidiaries and require their bank subsidiaries to be separately capitalized and regulated. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s proposed approach for resolving failed systemically important financial institutions involves transferring the assets of a bank’s parent holding company to a new bridge entity, while allowing solvent banking subsidiaries to continue operating throughout the period of reorganization.

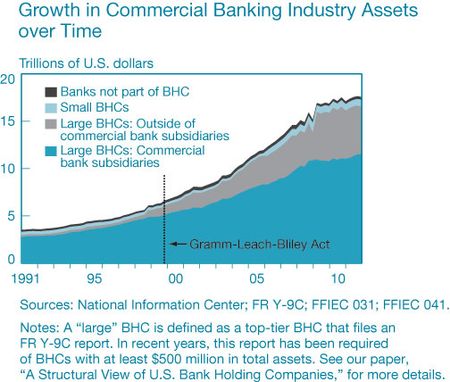

Nearly all the assets of the commercial banking industry are held within a bank holding company structure, as shown in the chart below. In past decades, commercial banking subsidiaries accounted for the lion’s share of BHC assets. However, this has changed markedly over time. The rapid growth in BHC assets held outside these bank subsidiaries (the gray area on the chart) reflects changes in the legislative environment; most prominently, the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act in 1999 allowed BHCs to engage in a broader range of commercial activities, including investment banking and insurance. Notably, almost all the growth in nonbanking assets dates to the period following the passage of the Act.

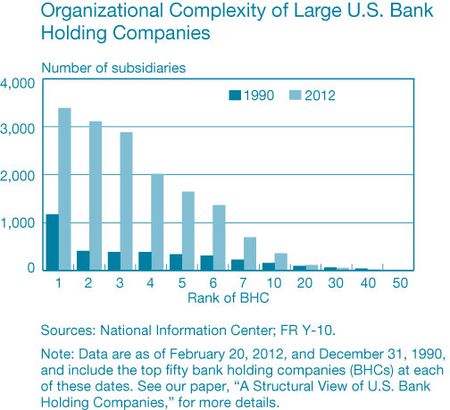

Next, we present one crude measure of the organizational complexity of large BHCs—a simple count of the subsidiaries of each firm. To construct this figure, we use data from bank regulatory filings of organizational structure, which are publicly available from the National Information Center. For 2012 and 1990, we count the number of subsidiaries of each BHC and sort them in descending order by firm. Today, two BHCs control more than 3,000 subsidiaries, and each of the six most organizationally complex BHCs controls more than 1,000 entities. In contrast, in 1990, only one BHC controlled more than 500 subsidiaries.

Only a small number (generally between one and five) of each BHC’s subsidiaries are traditional depository institutions. These banking subsidiaries generally control a majority of the BHC’s assets, although even here there is enormous variation across firms. For example, among the seven largest BHCs, we estimate that the fraction of assets held within commercial bank subsidiaries ranges from 3.2 percent to 92.5 percent of total consolidated BHC assets, as of December 2011.

Our EPR article describes these trends and stylized facts in more detail and considers measures of BHC scope across industries and geographic locations. In addition, we present a preliminary statistical analysis of the determinants of organizational complexity, as proxied by the number of subsidiaries. Larger firms are more complex by this measure; we also find some weak evidence that organizational complexity is positively related to the diversity of the BHC’s activities across industrial sectors and geographic locations.

What does the future hold for BHC size, structure, and scope? As always, the regulatory environment is a key driver of industry trends. Most notably, the “Volcker Rule” provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act represent a partial reversal of the previous decades-long trend toward enlarging the scope of permissible BHC activities. These new provisions prohibit BHCs from engaging in proprietary trading and limit their investments in hedge funds, private equity, and related vehicles.

Also under active debate is the appropriate scope of BHCs’ commodity trading activities. The Bank Holding Company Act restricts BHCs’ ability to own or trade physical commodities, or to own related hard assets like storage tanks, shipping containers, and warehouses. But a “grandfathering” exemption has allowed some investment banks to continue to trade and own significant volumes of physical commodities. However, the legal scope of the exemption is widely seen as ambiguous; for example, it is unclear to what extent it allows a firm to purchase new assets related to an existing commodities business, or to expand into new commodities markets. Media reports have speculated that the Federal Reserve may tighten its treatment of the exemption.

It seems possible that these regulatory developments may lead to some refocusing of BHC strategies toward traditional banking activities. Broadly speaking though, the largest BHCs will continue to be complex, diversified, internationally active organizations. As documented in our EPR article, BHCs and their subsidiaries do file an array of publicly available regulatory data on their activities—helping policymakers, investors, researchers, and others to “peel the onion” and obtain a detailed picture of the structure and behavior of these important firms.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Dafna Avraham is an assistant economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Patricia Selvaggi is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

James Vickery is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Gramm-Leach merged two long standing policy objectives: i) broadening the scope of activities in which BHC conglomerates could engage (thereby promoting profitability); and ii) preserving the segregation of bank entities within those conglomerates. It had nothing to say about BHCs engaging in swaps (which were simply an unregulated product pre-DFA). However I think there’s a good policy argument for requiring BHC’s engaged in swaps to adopt FHC status (ie subject to higher regulatory capital minimums) – haven’t heard anyone raise this though.

Thanks very much for these comments. As many readers of this blog might be aware, there’s an active debate amongst financial economists about the costs and benefits of breaking up large banks. Some researchers have estimated that there are significant scale economies in banking — in other words, large banks are more efficient and have lower expenses. If that’s true, then enforcing size limits on banking organizations could push up costs, which in turn would be passed on to households and firms in the form of less attractive interest rates or new fees. Others, however, argue that these efficiencies are overstated, and that the largest banks are “too big to fail,” giving them incentives to take excessive risks. There is a related debate about the scope of large banks. The graph in our blog post seems to suggest that Gramm-Leach-Bliley played an important role in increasing the range of activities that large BHCs are involved in. One could argue that this actually is a good thing, perhaps because of efficiencies of scope, but also because it makes these firms more diversified. For example, specialized investment banks such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers generally fared worse during the financial crisis than diversified BHCs. But it’s far from settled whether this is the right interpretation — some older academic research on this topic argues that banks simply undo any stability benefits of greater diversification by taking on more risk. Here are some links to related writing on these issues, for those who are interested: Scale economies in banking (from Fed economist Loretta Mester): http://www.minneapolisfed.org/publications_papers/pub_display.cfm?id=4535 http://www.phil.frb.org/research-and-data/publications/working-papers/2011/wp11-27.pdf The case for size limits on banks (from MIT professor Simon Johnson): http://baselinescenario.com/2012/05/12/making-banks-small-enough-and-simple-enough-to-fail/ The relationship between bank size, diversification, and risk-taking: http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/research_papers/9506.html

Every crisis has its good news: banks get smaller and hopefully will be more regulated and controlled. Every of us are paying th desastrous management of these guys.

I have always believed that this entire crisis had its origination in the Gramm-Leach Act. The banking industry ran through it like wild horses and its been a disaster ever since.