Rajashri Chakrabarti, Amy Farber, and Basit Zafar

One hundred and fifty years ago, the Morrill

Act

was signed into law, transforming the face of American higher education. The Act,

officially titled An Act Donating Public

Lands to the Several States and Territories which may provide Colleges for the

Benefit of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts had as its main purpose the

creation of “at least one college in each state where the leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific or classical studies, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts . . . in order to promote the liberal and practical education of industrial classes.”

Introduced by Vermont Congressman Justin Morrill, the Act laid the groundwork for a national system of public universities. It granted each state 30,000 acres of federal

land for each member of the Congress the state had. This land, or the proceeds

from its sale, were to be used to establish and fund universities that focused

on agriculture and engineering. Many of our leading universities (including MIT, Cornell,

the University of California

at Berkeley, and other universities that figure in U.S. News and World Report’s

top twenty-five list) were born of this law.

The Morrill Act also made higher education more democratic. Prior to the Morrill Act, higher education was largely the domain of the elite. The Act’s support for practical studies in agriculture and engineering helped other groups in the population, including farmers and working people, obtain a university education.

Twenty years after the first Morrill Act, the Second Morrill Act was passed in 1890. Under this Act, each state was required to show that “race

was not an admissions criterion, or else to designate a separate land-grant

institution for persons of color.” Many of our Historically

Black Colleges and Universities were established under this Act. Later, the 1994 Land Grant Institutions

for Native Americans received cash from Congress in lieu of land to attain

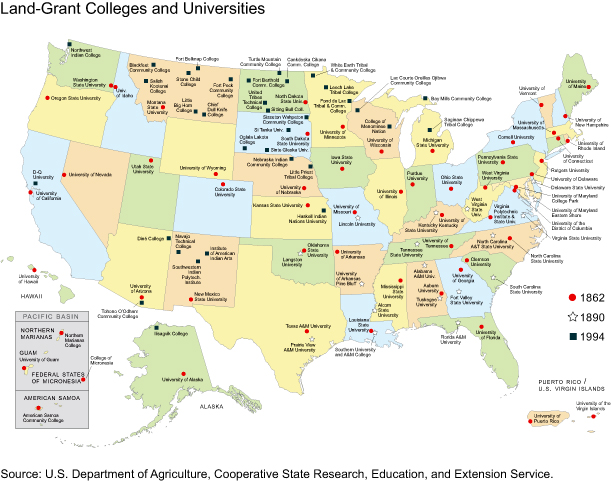

“land grant” status. These Morrill Acts established a total of 106 land-grant

universities, including at least one in each state. The distribution of these

1862, 1890, and 1994 land grant institutions is shown in the map below,

courtesy of the United

States Department of Agriculture. Following on the

lines of the Morrill Act, Congress later established sea grant

colleges (aquatic research, 1996), urban grant colleges

(urban research, 1985), space

grant colleges (space research, 1988), and sun grant colleges

(sustainable energy research, 2003).

As we celebrate the sesquicentennial anniversary of

the Morrill Act, it is worth taking a few moments to consider the current

higher education scenario, and the path it is taking. As we demonstrated in our

recent Liberty Street Economics post, public support for higher education has fallen precipitously in recent years. In fact, state and local funding (as a percentage of total revenue for public institutions of higher education) has fallen every year over the past decade, dropping from 71 percent in 2000

to 57 percent in 2011. The revenue crunch has forced public institutions to

seek alternative avenues for funding. For one, they have resorted to shifting more

of the costs of education to students. Our recent post finds an economically

significant relationship between public funding cuts and public institution

tuition hikes. In fact, in the post-recession period, the states with the

deepest funding cuts were also the ones with the highest growth in tuition. For

the average student, this translates to ever-increasing student loans and

potentially larger debt burdens.

America’s public universities constitute the backbone of our nation’s higher education system. One hundred and fifty years ago, the Morrill Act brought higher education to the masses. In these times of fiscal stress, the states can take a lesson from the Morrill Act. State reinvestment in higher education can go a long way toward fostering and promoting higher education.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is an economist in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

Amy Farber is a research librarian in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

Basit Zafar is an economist in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics