Anna Kovner

In a new working

paper, Josh

Lerner and I explore how the

venture capital (VC) model can be harnessed to achieve socially targeted ends

by examining the investment record of community development venture capital (CDVC)

firms. Our results are mixed. Investments made by CDVC firms are less likely to

succeed than are investments made by traditional VC firms. This lower

probability of success persists even after controlling for the fact that CDVC

firms invest in industries and geographies that have, on average, lower success

rates. However, we do find that CDVC firms have the benefit of bringing

traditional VC firms to underserved regions; controlling for the presence of

traditional VC investments, we find that each additional CDVC investment draws an

additional 0.06 new traditional VC firms to a region.

What Is Community Development Venture

Capital?

Broadly defined, community development venture capital is equity capital

invested with the goal of increasing economic opportunity and promoting

investments for underserved populations in distressed communities. In the

United States, these efforts can be traced back to the Small Business Investment

Company (SBIC) program, the

Minority Enterprise Small Business Investment Companies (MESBICs), and the

numerous community development corporations set up in response to the “War on

Poverty” in the 1960s, which sought to alleviate poverty through the

application of business principles.

More recently, beginning in 1992,

the Ford

Foundation and the John D.

and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

began backing a trade association of CDVC funds, the Community Development

Venture Capital Alliance (CDVCA). The

establishment of the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Community Development

Financial Institution (CDFI)

Fund, which was established by the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory

Improvement Act of 1994, also boosted investment activity.

We identify CDVC firms from two

sources. The Community Development Venture Capital Alliance has maintained a

roster of members on its website. We use the current and archived versions of

this list (obtained through web.archive.org). Additionally, the Treasury’s CDFI Fund has undertaken periodic

surveys of entities receiving its funds. We identify from these surveys all

CDFI funds that have made equity investments. We then match these lists of VC firms

against the firms identified in VentureXpert. Of fifty-seven potential CDVC firms identified, we match thirty-two VC

firms to VentureXpert. Twenty-eight of these firms have made U.S. investments

tracked by VentureXpert.

CDVC Firms Are Different from Traditional

VC Firms in Their Locations and Investments

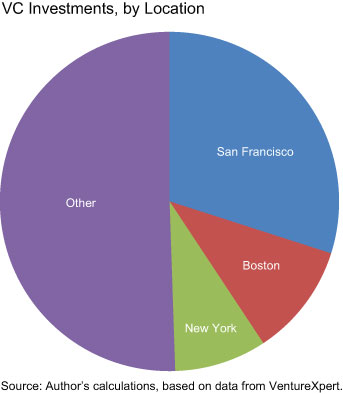

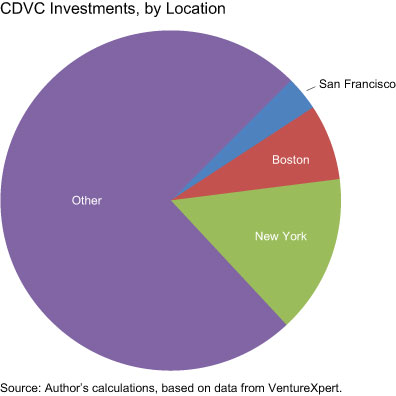

We first examine how the composition of investments by community

development venture funds differs from those of traditional groups. We find

substantial differences: Community development fund investments are far more

likely to be in nonmetropolitan regions and in regions with little prior

venture activity.

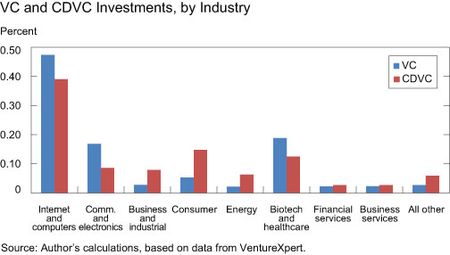

Similarly, CDVC investments are

likely to be in earlier-stage investments and in industries outside the venture

capital mainstream (Internet, biotech, and communications and electronics). Investments

in which traditional VC firms invest alongside CDVC firms share many of these

features, but are more likely to be in the traditional VC industries.

We find the CDVC sector to be

relatively small in terms of investments that are comparable to those made by

traditional VCs; in total, we find 305 investments by twenty-eight CDVC firms,

compared with more than 65,000 investments by more than 5,500 non-CDVC funds. We

also document several other significant differences between the two types of

funds and their investments.

The CDVC firms are more likely to

invest in earlier financing rounds, reflecting an orientation toward seed and

early-stage investing.

The firms backed by CDVC firms have

fewer venture investors participating in the rounds and have undertaken fewer

financing rounds in total. However, in part, this may reflect these firms’

relative youth (see below).

The CDVC-backed firms are

substantially less likely to have gone public (1 percent versus 13 percent) or

to be successful (18 percent versus 33 percent). Again, the relative youth of

these firms must lead us to be cautious in interpreting the results.

The CDVC-backed investments were

likely to occur later than non-CDVC investments even though we begin the sample

in 1996, reflecting the relative youth of the sector.

CDVC Investments Are Less Likely To Go

Public or To Be Acquired

When we turn to considering the success of CDVC investments—as measured by

the probability of going public or being acquired—we find that the types of

deals in which CDVC investments are concentrated have a lower probability of

success in general. Even after controlling for this unattractive transaction

mixture, however, the probability of a CDVC investment being successfully

exited is lower.

CDVC Firms May Have Broader Impact

Investment returns are not the only possible measure of success of CDVC

firms. While the relationship between the number of VC firms and the number of

VC investments in a region is inherently difficult to estimate, we investigate whether

the presence of CDVC firms and CDVC investments is associated with an increased

number of non-CDVC firms. Controlling for the presence of traditional VC

investments, we find that each additional CDVC investment results in an

additional 0.06 new traditional VC firms in a region. Of course, this result

must be interpreted cautiously because it is possible that CDVC firms are

simply investing in areas where traditional VC firms are planning to grow. If

CDVC firms really do increase the likelihood that traditional firms locate or

invest in underserved regions, they play an important indirect role in facilitating

economic growth. A number of papers document that traditional venture capitalists

play an important role in facilitating growth (see, for example, Kortum

and Lerner (2000).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Anna Kovner is a senior financial economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics