Thomas Klitgaard and Ayşegül Şahin

Euro area GDP remains below its 2007 level due to the global financial meltdown and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis in the periphery countries. Unemployment rates make it clear that some countries have fared much worse than others—the rates in Spain and Greece today are over 25 percent and are much higher than rates in the next highest, Portugal (15.7 percent), and in the euro area (11.6 percent). Quite a change from 2007, when Spain and Greece had lower unemployment rates than the euro area as a whole. In this post, we show that while the unemployment rates in the two countries are similar today, the paths have been very different. The employment decline in Greece, like in the

euro area, has been proportional to the country’s steep decline in GDP; Spain’s employment has fallen much more than output, due in part to its notable labor market flexibility.

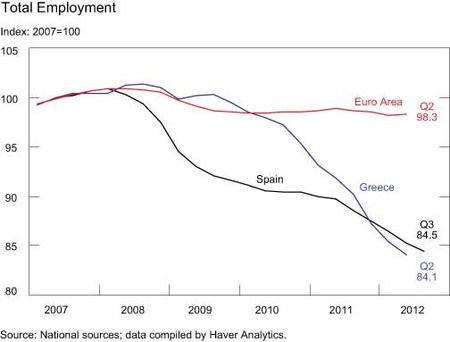

A look at total employment for Greece and Spain in the chart below shows the large percentage declines in the two countries since 2007. Job losses started earlier in Spain, with the collapse of a housing bubble, while Greece managed to keep employment levels stable, in line with the euro area as a whole, before its sovereign debt crisis caused very steep declines in employment beginning in 2010. In both countries, employment in 2012 is down roughly 15 percent from 2007 levels.

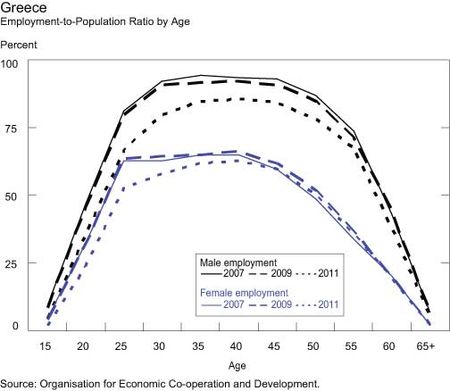

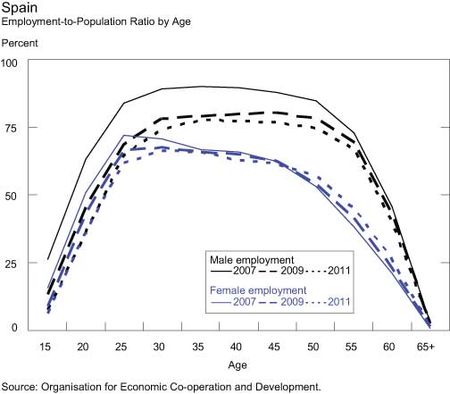

The demographic aspects of the drop in employment are also similar in the two countries. In the charts below, the solid lines represent employment-to-population ratios across age groups in 2007. The dashed

lines are for 2009, covering the initial euro area downturn, and the dotted

lines are for 2011, highlighting the impact of the sovereign debt crisis. Black lines represent males and blue lines females.

The charts illustrate that male workers and the young suffered the biggest employment losses in Greece and Spain. Older workers fared the best, with older males largely holding their ground while older females

achieved gains. A factor behind the better performance of older workers in the two countries may be delayed retirement decisions in the face of economic uncertainty.

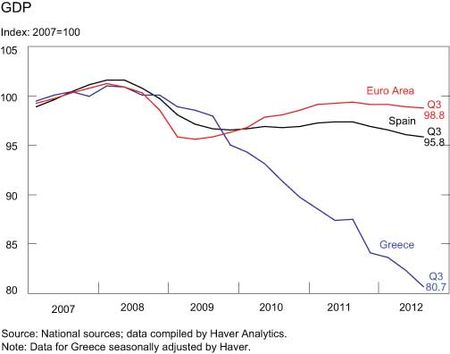

The appearance that the job losses were similar in nature, though, vanishes when compared with the size of output declines in the two countries. In 2012:Q3, euro area output was down 1 percent from its

2007 level. Spain has done poorly relative to the region, with output down

4 percent, but this decline is small compared with that of Greece, which

has suffered a 19 percent drop. The percentage declines in output and

employment are roughly equal in Greece and the euro area as a whole, but job losses in Spain have been much larger than the decline in output.

The high unemployment rate in Greece is not surprising given the depths of its recession, but what explains Spain’s 25.8 percent unemployment rate given its much more modest downturn? One contributing factor is the fact that the composition of Spanish jobs made the economy vulnerable to dramatic job losses during a recession. In 2007, almost 13 percent of jobs in Spain were in construction, compared with roughly 8 percent in Greece and the euro area. Such a heavy weight on this sector made employment more vulnerable to a downturn given the fact that construction is the sector that typically experiences the steepest decline in a recession. Indeed, construction, as measured in the GDP accounts, fell 35 percent from 2007 to 2011, and the sector accounted for almost 60 percent of the decline in total employment over this period.

Another contributing factor is the very high percentage of employees tied to temporary work contracts in Spain. Data from the Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development show that 32 percent of employees in Spain worked under temporary contracts and 68 percent under permanent contracts in 2007. In Greece, 10 percent were on temporary contracts; the figure for Europe as a whole was 15 percent.

This unusually high reliance of the economy on temporary contracts may well have supported job growth in Spain before the recession. Firms should be more willing to hire workers with temporary contracts during an upturn if they know that hires can be let go at a relatively low cost. In a downturn, this arrangement makes it easier for firms to shed jobs.

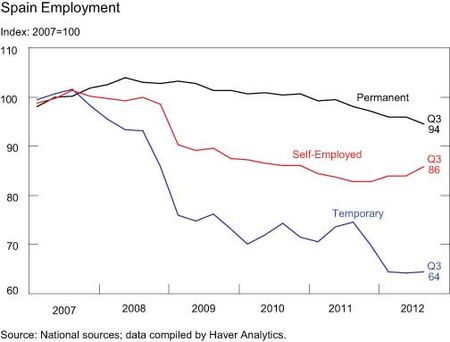

Spain’s labor force survey breaks down employment into the self-employed, employees with permanent contracts, and employees with

temporary contracts. As expected, the employment losses since 2007 are heavily weighted to temporary workers (-36 percent), followed by the self-employed (-14 percent). At the same time, the number of employees with permanent job contracts fell by a much more modest amount (-6 percent).

Spain’s employment experience relative to the rest of the euro area illustrates the cost to the economy of firms having such a high level of flexibility in how they manage workers. Going forward, the hope is that the benefits of such a flexible labor market will also become apparent as firms are quick to hire once the economy starts to make a meaningful recovery.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Research and

Statistics Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Ayşegül Şahin is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics