Jaison R. Abel, Jason Bram, Richard Deitz, and James A. Orr

While the full extent of the harm caused by superstorm Sandy is still unknown, it’s clear that the region sustained significant damage and disruption, particularly along the coastal areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. As we describe earlier in this series, the economic costs associated with natural disasters are generally thought to arise from the damage and destruction of physical assets and the loss of economic activity. These costs can be substantial, running into the tens of billions, and impose significant stress on the affected communities. In this post, we assess who will ultimately pay the economic costs imposed by the storm. Based on data from recent hurricane events, it is likely that the federal government and private insurance companies will more than cover the aggregate costs. In the short run, though, there may be strains on state and local governments as well as on individuals and businesses as they await reimbursement.

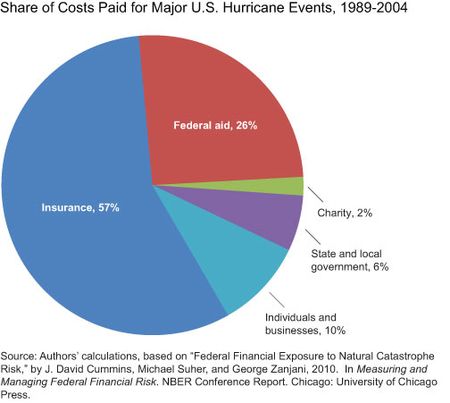

It’s useful to group the parties that will ultimately bear the economic costs of Sandy into five categories: private insurance companies, the federal government, state and local governments, charities such as the American Red Cross, and the individuals and businesses in the communities directly impacted. The chart below, which is based on data from a recent study, provides a rough estimate of how the economic costs have been shared during major U.S. hurricane events from 1989 to 2004, just before Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf region. During this period, private insurance companies paid about 57 percent of the cost on average. Federal disaster relief—primarily funds distributed through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)—accounted for another 26 percent, although this figure is likely low as it doesn’t include funds provided by the National Flood Insurance Program. Estimates based on typical government cost-sharing arrangements that exist for natural disasters put the state and local government share at about 6 percent of the overall cost. Charities tend to contribute a couple percent. Finally, individuals and businesses affected by a major hurricane during this period covered about 10 percent of the cost.

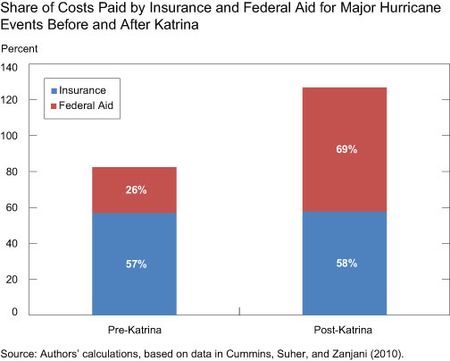

The story changes significantly following Katrina. As the next chart shows, the share paid by insurance companies held steady, while the share paid by federal disaster relief increased substantially, from about 25 percent before Katrina to nearly 70 percent after. Some of this increase reflects more generous federal reimbursement to state and local governments, in part for projects to help mitigate the effects of future storms. The Stafford Act, a 1988 law designed to guide the process of relief following a natural disaster, stipulates that the federal government reimburse a minimum of 75 percent of state and local government costs. In hurricanes prior to Katrina, the rate was generally between 75 and 90 percent. However, beginning with Katrina, state and local governments often received 100 percent reimbursement. With this expansion of federal disaster assistance, payments from private insurance companies and the federal government exceeded the total economic cost of events since Katrina by about 25 percent. This pattern suggests that an excess amount was distributed to state and local governments and affected individuals and businesses, although it’s not clear in what proportion. Clearly, though, some businesses or individuals may not have been fully reimbursed for their out-of-pocket expenses, despite the excess payments in aggregate.

Even with private insurance companies and the federal government ultimately picking up some or all of the costs associated with events like these, state and local governments in the affected areas typically fund a significant amount of the relief effort up front. Brookhaven, New York, for example, was still receiving funds from the federal government a year after Hurricane Irene struck in 2011. Delays can create immediate fiscal strain on state and local governments, especially small municipalities, because they typically must balance their budgets annually. Such stresses have already emerged in the hardest-hit areas of the region. Municipalities can respond to these fiscal pressures by borrowing money to help cover immediate costs—either directly from banks or by floating bonds—or they may choose to temporarily raise taxes. Individuals and businesses may also face their own set of financial challenges as they await reimbursement.

If history is a guide, the tri-state region should receive a considerable amount of help in paying for Sandy, particularly from the federal government. New York State and New Jersey have asked for full reimbursement of the costs of the storm, plus funds for preventing and mitigating the effects of future events, with the requested amounts totaling $42 billion and $37 billion, respectively. The promise of reimbursement may only be faintly reassuring to those already beginning to pay for Sandy, and these payments, of course, will not cover the welfare costs associated with the suffering the storm caused. Going forward, the large and increasing role of the federal government raises a number of important public policy questions about who should bear the risk and financial burden of natural disasters. In the meantime, the availability of these resources will be instrumental in helping the region rebuild and recover from Sandy’s damage.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jaison R. Abel is a senior economist in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jason Bram is a senior economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics