Gara Afonso

In

the fall of 2008, the Fed added new policy tools to its portfolio of techniques

for implementing monetary policy. In particular, since October 9, 2008,

depository institutions in the United States have been paid interest on the

balances they hold overnight at Federal Reserve Banks (see Federal Reserve Board announcement). Several other central

banks, such as the European Central Bank (ECB) and the central banks of Canada,

England, and Australia, have somewhat similar deposit facilities allowing banks

to earn overnight rates on their balances. In this post, I discuss the benefits

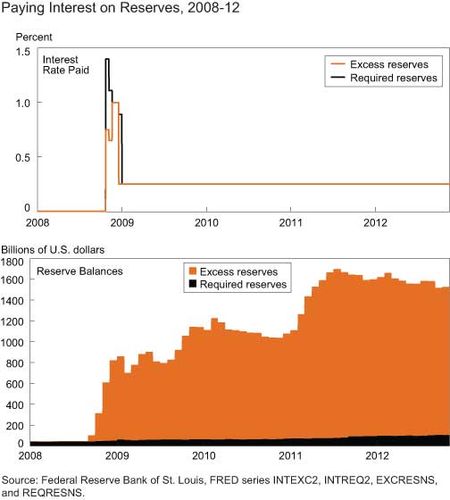

and costs of this new tool in an environment where excess reserves in the

United States have now exceeded $1.4 trillion and account for close to 95

percent of all reserves.

It has typically been argued that the interest rate

paid by central banks on required reserve balances effectively compensates

depository institutions for the implicit tax that reserve requirements impose

on them, while the interest rate paid on excess balances provides the central

bank with an additional tool for conducting monetary policy. Central banks

differ, however, in the strategies they use to implement the rates paid on

excess reserves. For example, the ECB does not pay interest on excess reserves

directly but instead offers a deposit facility where banks can place excess

reserves overnight. The Fed, by contrast, pays interest on depository

institutions’ excess balances directly.

Since the implementation of this new policy in the

United States, reserves have increased to unprecedented levels (see chart

below). And although there is no doubt that adding a new tool has strengthened

the Fed’s ability to conduct monetary policy, some economists have recently

begun to discuss the current costs and benefits of remunerating excess

reserves: Should the trade-off between benefits and costs be reconsidered at

this time? Or put differently, how would it matter if the Fed lowered the

interest rate on excess reserves?

My recent paper with Ricardo Lagos of New York University can help

answer such questions. This work provides a search-based model of the U.S.

interbank market that captures some of the market’s key institutional features,

including its decentralized (over-the-counter) nature. This feature is

important because it means that banks must first find a potential counterparty

with which to negotiate the terms (size and rate) of a loan before borrowing and

lending can actually take place.

In a stylized version of the model, the rate negotiated

between a borrower and lender can be understood as a weighted average of their

outside options—that is, a weighted average of the return that a lender would

earn if it did not make the loan and instead kept the reserves in its account

at the Fed overnight (interest on excess reserves) and the rate that the

borrower would have to pay if it could not get a loan and needed to borrow from

the discount window (discount window rate and other penalties such as stigma).

The weights capture the bargaining power of borrower and lender and, more

important, the aggregate level of reserves. When excess reserves are very high

relative to the level of required balances, as is the case in the United States

at present, the weight on the interest paid on excess reserves is very close to

one, and changes in interest on excess reserves translate almost one-to-one

into changes in the federal funds rate. In current market conditions, this

would mean that reducing the rate the Fed pays on excess reserves would push

the fed funds rate to near zero.

The textbook benefit of lowering interest rates is the stimulative

effect on economic activity. The tactic is generally used by central banks to

reduce the real cost of borrowing and encourage consumption and investment when

the economy starts to weaken. However, it has been suggested that the

effectiveness of lowering rates may be limited when rates are already very

close to zero. Another benefit of reducing rates would be to lower money market

rates and stimulate bank lending, although the effect may also be marginal in

the current environment. An additional argument in favor of lowering rates can

be found in traditional and recent theories of money that typically argue that

a zero nominal interest rate leads to an optimal allocation of resources in the

economy.

What about the costs of lowering rates? Reducing rates

in an ultra-low-interest-rate environment may lead to a deflationary spiral.

However, many economists have suggested that the risks of a deflationary trap

are probably small.

Additional costs were also pointed out at the Federal

Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting held on September 20-21, 2011 (see Minutes). When discussing the possibility of lowering the

interest paid on reserves, participants at the meeting raised concerns that a

close-to-zero rate could lead to disruptions in several financial markets. In

particular, lowering rates could further depress the volume traded in the

federal funds market. In a thinner market, the rate could then be driven by

infrequent transactions that are no longer representative of overnight

borrowing costs. The information that this rate may convey would then be lost.

Very low interest rates could also place money markets funds under stress—an

outcome that could disrupt access to short-term credit for some borrowers,

including large firms. As pointed out by Todd Keister in a post on November 16, 2011, on the zero lower bound,

financial distress could also reach the U.S. Treasury market if rates were to

become negative.

Overall, reducing the rate paid on excess reserves

would push the fed funds rate closer to zero, which could have detrimental

effects on several financial markets. Uncertainty about the scope of these

disruptions to financial markets seems to be preventing central banks from

lowering rates further.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Gara Afonso is an economist in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics