Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz

U.S. households accumulated record-high levels of debt in the 2000s, and then began a process of deleveraging following the Great Recession and financial crisis. In some parts of the country, the rise and fall in household indebtedness was quite a bit sharper than in others. In this post, we highlight some of our research examining the magnitude of the recent credit cycle, and focus on how significant it’s been in New York State and northern New Jersey. Compared with the nation as a whole, we find that the region experienced a relatively mild credit cycle, although pockets of elevated household financial stress exist.

The Increase in Household Indebtedness

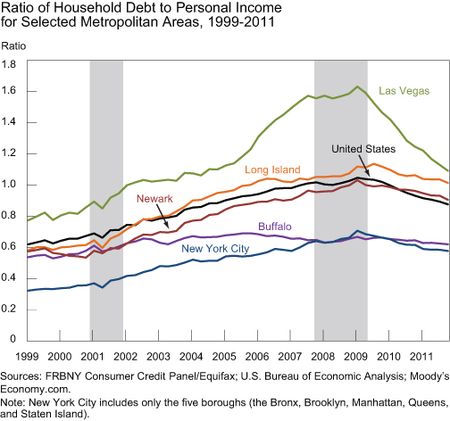

The chart below shows the national debt-to-income ratio, a measure of the magnitude of household indebtedness, which we define as aggregate debt divided by aggregate personal income. The ratio increased until late 2007, then held fairly steady at a value of around 1—debt essentially equal to annual personal income—until 2009, when it began to decline modestly (see the New York Fed’s latest quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit for more details on household finances). However, in some places household indebtedness grew much more rapidly than average. Because the vast majority of debt that households owe is associated with their homes (such as mortgages and home equity lines of credit), it should come as no surprise that the rise in household debt largely reflected the degree to which local housing markets boomed. For example, in Las Vegas the debt-to-income ratio doubled from around 0.8 in 1999 to more than 1.6 in 2009.

There wasn’t a strong boom in many of the housing markets in the New York state–northern New Jersey region, which helps explain the slower run-up in debt in the area. For example, debt rose very little in Buffalo compared with the national pace. In large part, this pattern reflects the slow home price appreciation in Buffalo during the housing boom, which was the case throughout much of upstate New York (see our 2010 Current Issues in Economics and Finance article). While household indebtedness in New York City held well below that of the nation, in part because a significant percentage of households in the city rent and thus carry no mortgage debt, it increased at around the national pace. In Long Island and Newark, where the housing market generally mirrored the U.S. market overall during the boom, household indebtedness grew at a pace similar to the nation’s.

The Decline in Debt Burdens following the Recession

Household finances came under increasing pressure during the Great Recession and the financial crisis that followed. Households began a process of deleveraging—that is, reducing their debt burdens—a process that has continued through the slow recovery (a recent Liberty Street Economics blog post discusses household deleveraging in more detail). Such declines have not just been a result of debt repayment, but also reflect defaults, which can be triggered by home price declines that put borrowers “underwater” (when a borrower’s house is worth less than what’s owed on it). For the nation as a whole, the debt-to-income ratio declined about 16 percent, from 1.05 at its peak to about 0.88 by year-end 2011. In some parts of the country, the ratio declined much more substantially, particularly in places where debt had grown most rapidly and where housing prices fell the most. In Las Vegas, for example, the debt-to-income ratio declined 33 percent, from a peak of 1.63 to 1.09. Across the New York-northern New Jersey region, the pace of the decline in indebtedness has been generally below average, and has been especially moderate in upstate New York. The decline in the ratio in New York City was on par with the national decline, while it fell 11 to 12 percent in Long Island and Newark and was down just 7 percent in Buffalo.

The Credit Cycle and Household Financial Stress

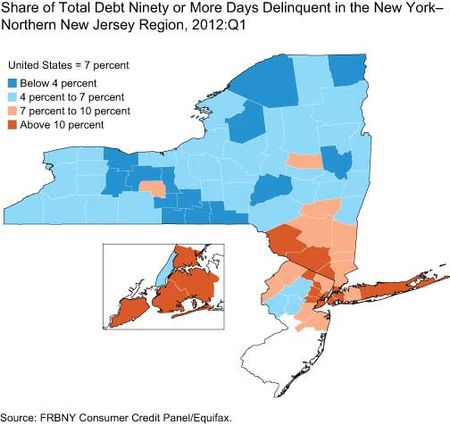

Taken as a whole, the rise and fall in household indebtedness suggest that the magnitude of the credit cycle has been somewhat milder in downstate New York and northern New Jersey, and quite a bit milder across upstate New York, when compared with the nation. Nonetheless, pockets of concentrated financial stress are still clearly visible in the region. The map below shows delinquency rates by county for the New York–northern New Jersey region (more detailed data on regional mortgage conditions are available on the New York Fed’s website).

The vast majority of counties in upstate New York have delinquency rates well below the national rate. However, delinquency rates downstate are above the national average, with particularly high rates in Sullivan, Orange, and Rockland Counties. High delinquency rates also appear in the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn as well as in parts of Long Island, though Manhattan’s rate is well below the national average. Rates are also high across most counties in northern New Jersey. Thus, despite the fact that the increase and decrease in local debt burdens were less pronounced than in the nation as a whole, pockets of especially high household financial stress do exist in the region. In part, the relatively high stress in these places stems from sharp home price declines coupled with a deeper recession and weaker recovery than in other parts of the New York-northern New Jersey region.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jaison R. Abel is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics