Mary Amiti, Oleg Itskhoki, and Jozef Konings

Why do large

movements in exchange rates have small effects on international goods prices? This

empirical regularity is a central puzzle in international macroeconomics. In a

new study, we show that the key to understanding this exchange rate disconnect is to take into account that the largest

exporters are also the largest importers. This is important because when exporters

import their intermediate inputs, they face offsetting exchange rate effects on

their marginal costs. For example, a depreciation of the euro relative to the U.S.

dollar makes exports in U.S. dollars cheaper—but it also makes imports in euros

more expensive. Using Belgian firm-level data, we show that exporters that

import a large share of their inputs pass on a much smaller share of the

exchange rate shock to export prices. Interestingly, import-intensive firms typically

have high export market shares and hence set high markups and actively move

them in response to changes in marginal cost, thus providing a second channel

that limits the effect of exchange rate shocks on export prices. Our results

show that a small exporter with no imported inputs has a nearly complete pass-through

of more than 90 percent, while a firm at the 95th percentile of both import

intensity and market share distributions has a pass-through of 56 percent, with

the two mechanisms playing roughly equal roles. These findings have important implications for

aggregate macroeconomic variables.

The Data

The National Bank of

Belgium, our primary data source, provides highly disaggregated export and

import data at the firm level. The data set includes information on

approximately 10,000 distinct product categories by destination and source

country. We use unit values to proxy for a firm’s export price, defined as the

ratio of export value to export quantity. One potential problem with this

measure is that, even within this fine level of disaggregation, there may still

be compositional shifts within the product categories. However, studies that

draw on price data have not been able to match import and export prices at the

firm level.

Most importantly, using the trade data enables us to construct an exporter’s

import intensity, which is an essential ingredient for this study. The firm’s

import intensity is defined as the ratio of imported intermediate inputs to

total variable costs as described in our theoretical framework. It is important

to know the country source of a firm’s imports so that we can net out the

imports originating from within the euro zone since these are in the same

currency as Belgium domestic costs. In order to get a measure of the firm’s

total variable costs, defined as total material costs plus the wage bill, we

merge the trade data with firm-level characteristics. We can also directly

measure a firm’s marginal cost that is potentially sensitive to exchange rate

movements as an import-weighted change in the firm’s import prices, which we

proxy for using unit values (the ratio of import value to import quantities). The

final key ingredient in the study is a measure of the firm’s market share in

each destination, which we construct for each firm-product-destination-time.

This measure is an indicator of the firm’s mark-up variability.

Stylized Facts about Exporters and

Imports

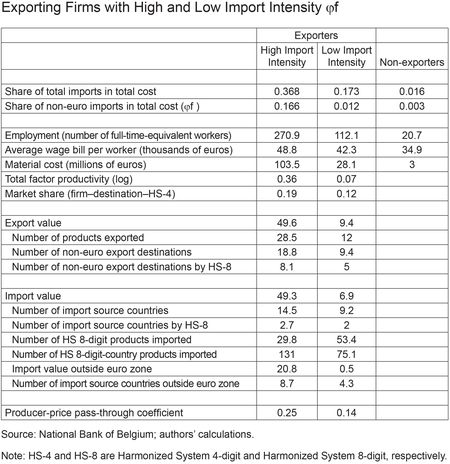

A new interesting stylized fact to emerge from our analysis is that there

are large systematic differences across exporters. Previous studies have

emphasized the differences between exporters and non-exporters, highlighting

that exporters are bigger, more productive, and pay a wage premium—features

that are also present in our data. However, even within the select group of

firms that are exporters, there are very large differences between high

import-intensive exporters and low import-intensive exporters. Splitting the sample

based on the median import intensity, we show in the table below that

import-intensive exporters are larger in terms of employment and material

costs, pay higher wages, are more productive, have higher market shares, export

higher values, and export to more destinations; they also import more products

and from more countries. These patterns turn out to be important in explaining

the heterogeneity of exchange rate pass-through into export prices across

different firms. Furthermore, because high import intensity firms are also

firms with high export shares, these results help explain low aggregate

pass-through.

The Main Findings

Firm market share and import intensity are the two

key determinants of pass-through at the firm-level, consistent with the theory,

and explain a wide range of variation in exchange rate pass-through.

Specifically, small exporters have a nearly complete pass-through, that is,

they pass on almost 100 percent of the exchange rate change into export prices.

In contrast, the largest exporters, which are simultaneously the largest

importers, have an exchange rate pass-through of only slightly above 50 percent.

Roughly half of this incomplete pass-through is due to the offsetting effects

of an exchange rate change on marginal cost (which we proxy using the firm’s

import intensity), with the other half due to the variation in the markups

(which we proxy using the firm’s market share). Firms with large market shares

adjust their markups more than small firms in response to cost shocks. Furthermore,

since import intensity is heavily skewed toward the largest exporters, this

helps explain the observed low aggregate pass-through.

Indeed, a large share of exports comes from large firms that source their inputs

globally and are thus only partially linked to the domestic market conditions

in their home country. As a result, these firms are effectively hedged against

the exchange rate fluctuations and do not need to fully adjust their prices.

Furthermore, these are the strong-market-power firms, setting high markups,

which they actively move in response to shocks. Our results provide evidence

that high market share firms have more variable markups. To sum up, the prices

of the largest firms, accounting for the disproportionate share of trade, are

insulated from exchange rate movements both through the hedging effect of

imported inputs and active offsetting markup adjustment in response to cost

shocks.

Conclusions

We show that taking

into account that large exporters are also large importers can help explain

differences in exchange rate pass-through across firms as well as low aggregate

pass-through. Further, we decompose the incomplete pass-through into the

marginal cost channel and mark-up channel, finding a roughly equal contribution

of each channel. These results have important implications for international

macroeconomics as price sensitivity to exchange rates is central for the

expenditure-switching mechanism at the core of international adjustment and

rebalancing. Understanding why there is incomplete pass-through is important

from a welfare perspective as the implications differ if incomplete

pass-through is due to different distributions of markups across firms or to

complex global sourcing patterns, which directly affect marginal costs.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Mary Amiti is an assistant vice president in the Federal

Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Oleg Itskhoki is a professor of economics at Princeton

University.

Jozef Konings is professor of economics at University

of Leuven.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics