Benjamin R. Mandel and Geoffrey Barnes

An important measure of success for monetary policy is a central bank’s ability

to anchor inflation expectations; inflation expectations influence actual

inflation and, hence, the achievement of a given inflation goal. This notion has

special significance for Japan, where CPI inflation has been intermittently

negative since 1994 and where it is widely believed that expectations of future inflation have been persistently negative (that

is, ongoing deflation is expected). In this post, we describe and evaluate an

alternative, market-based measure of Japanese inflation expectations based on

international price parity conditions. We find that recent inflation

expectations have attained a level substantially higher than their previous

peaks over the past three years.

By way of background, recent policy

action by the Bank of Japan has shone a spotlight on Japanese inflation

expectations. On April 4, the Bank announced a program called Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary

Easing (QQE), which was a pledge to drastically ramp up asset

purchases to increase the monetary base, and to extend the duration of assets

held on the Bank’s balance sheet. Since nominal yields on Japanese government

bonds have been quite low for some time, a preferred indicator of QQE’s success

would be a decline in real interest rates as inflation expectations move closer

to the Bank’s recently announced 2 percent price stability target.

Measurement Issues

How does one go about measuring Japanese inflation expectations? The

consensus on this topic is that there is no single reliable measure. A commonly

used market-based gauge of U.S. inflation expectations is the difference in

yield between nominal and Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS)—the

breakeven inflation rate. Analogous measures come from over-the-counter

derivatives called inflation swaps. In Japan, the market for

inflation-protected government bonds, called JGBi’s, is very thinly traded and

a majority of the issuance has been bought back by the Ministry of Finance in

recent years. These factors have cast doubt on the ability of JGBi prices to

convey reliable information about inflation expectations. Swaps suffer from

similar liquidity issues.

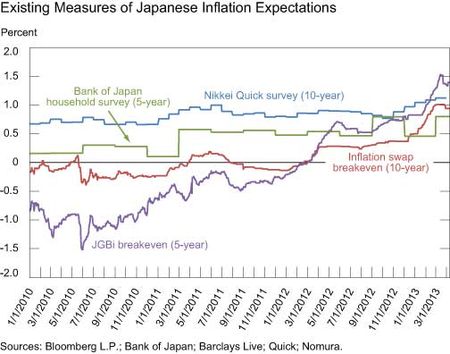

Alternative extant measures of

inflation expectations are available from surveys of households, investors, and

professional forecasters. However, survey responses may by formed in a

backward-looking manner, making them more responsive to actual inflation than predictive

of the future. The range of views offered by market‑ and survey-based measures

is illustrated in the chart below. While measures of five- and ten-year

expectations have converged somewhere around 1 percent in recent months, in the

past analysts would have little confidence of even getting the correct sign of

expected inflation by looking at any given measure.

A Measure Based on Purchasing Power Parity

Given these concerns, we consider an additional market-based measure derived

from U.S. inflation expectations—for which there are more actively traded

inflation‑protected securities and swaps markets—and international price parity

conditions. To our knowledge, these tools are not commonly used to make

inferences about Japanese inflation expectations, but may provide a useful

alternative to Japanese JGBi’s and swaps. One exception is a report by Goldman

Sachs Economics Research (“The Market Consequences of Exiting Japan’s Liquidity

Trap,” Global Economics Weekly 13/05,

February 2013), which uses the thirty-year yen/dollar forward rate to infer Japanese

inflation expectations.

The measure relies on purchasing power parity (PPP), which equates

the price level in one country to the price level in a second country and the

two countries’ nominal exchange rate. PPP has been shown to work relatively well

over longer periods as well as in relative terms; that is, it works better in

changes than in levels. In the case of Japan, PPP implies that the change in expected

future Japanese prices (a close analogue to inflation expectations) is equal to

the change in expected future U.S. prices plus

the change in the expected future value of the yen. We implement this measure

using the corresponding breakeven rate for U.S. inflation implied by TIPS and

the yen/dollar forward exchange rate.

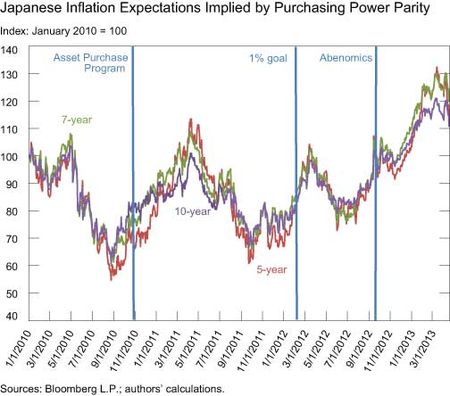

The chart below uses daily data and shows

the resulting PPP-implied Japanese inflation expectations for five-, seven-,

and ten-year horizons since January 2010. Note that the timing of fluctuations

in expectations suggests that they are related to policy actions, since each peak

over the past three years has followed a major policy innovation. In October

2010, the Bank of Japan’s introduction of the Asset Purchase Program

spurred a rise in expectations, which was then undone by mid-2011. In February

2012, the Bank introduced a 1 percent price stability goal,

which prompted another, less pronounced, change in inflation expectations that

was again undone after a few months. Most recently, inflation expectations have

increased following the election of Shinzo Abe as leader of Japan’s Liberal Democratic

Party in September 2012 and subsequently as prime minister in December, marking

the beginning of a policy regime commonly referred to as “Abenomics.” By our

measure, post-Abenomics inflation expectations have attained a level

substantially higher than the previous two peaks.

A Check of the Methodology

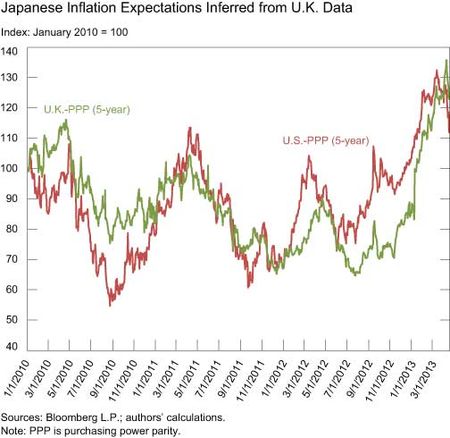

We can check the robustness of the PPP-implied measure by applying the same

logic to different country pairs. If the movements in our measure of inflation

expectations are not driven by idiosyncrasies in U.S.-Japan financial markets,

then substituting another nation’s forward exchange rate and breakeven inflation

rate for the respective U.S. rates should yield similar results. The United

Kingdom is a natural candidate for the role of “other nation” here, given its

relatively liquid inflation-protected security markets. Hence, we use the

pound/yen forward rate and U.K. breakeven inflation rates to produce the

PPP-implied measure of Japanese inflation expectations shown in the chart below

(plotted alongside the analogous U.S.-based measure from above). While not always

perfectly aligned in levels, the two series have been highly correlated—with

a correlation coefficient of 0.66–in their day-to-day movements since 2010.

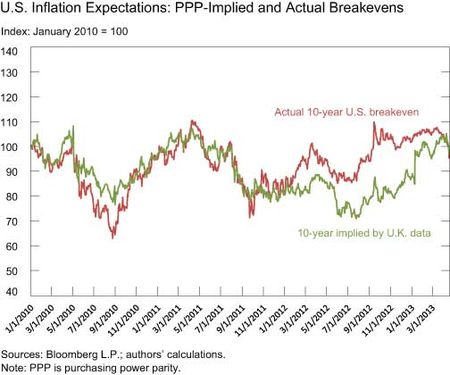

In a similar test of the methodology,

we compute a measure of U.S. inflation expectations as implied by U.K.

inflation expectations and the pound/dollar forward rate. The chart below plots

the resulting implied ten-year U.S. inflation expectations against actual U.S. breakeven inflation rates. With

the exception of a few days in late 2012 when the series diverged and then

converged again, the two measures are again closely correlated at a daily

frequency—with a correlation coefficient of 0.64. These findings suggest that

PPP provides a good approximation to U.S. TIPS.

In summary, PPP provides an

alternative, market-based view of Japanese inflation expectations, which appear

to have been quite responsive to recent monetary policy innovations by the Bank

of Japan. Moreover, the similarity of the measures across time periods (five-, seven-,

and ten-year) and country pairs (U.S.-Japan, U.K.-Japan, and U.S.-U.K.) gives

some comfort that PPP implies a robust reading of inflation expectations more

generally.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Benjamin R. Mandel is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's Research and Statistics Group.

Geoffrey Barnes is a senior research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics