Jaison R. Abel, Jason Bram, Richard Deitz, James A. Orr, Kaivan K. Sattar, and Eric Stern

The New York metro region’s recovery from Superstorm Sandy is well under way. Spending on restoration and rebuilding activities following a natural disaster is a potentially powerful economic stimulus to the affected area. Indeed, money from outside the region—in the form of federal aid and private insurance payments—flowing to the damaged areas in the region gives a temporary boost to economic activity. But does this mean that Sandy—along with the federal aid and insurance payouts associated with it—was actually good for the region’s economy? In this post, we examine the nature and magnitude of the stimulus the New York metro region is receiving as it recovers from Sandy and provide some thoughts on how the economy may be affected over the longer term by rebuilding activities.

A Boost to Economic Activity

Clearly, Sandy caused widespread damage and depressed economic activity in the region. No doubt, the funds the region is receiving as the hardest-hit areas recover will provide an offsetting boost to economic activity. The two main sources of recovery funds are the $60 billion in disaster relief appropriated by Congress and roughly $20 billion in receipts from private insurance settlements—the majority of which will go to New York and New Jersey. For the hardest-hit communities, this disaster assistance is quite large compared with the size of the local economies, and will play an essential role in the recovery. As a share of the broader regional economy, however, this funding is more modest, totaling about 6 percent of the New York metropolitan region’s $1.3 trillion economy.

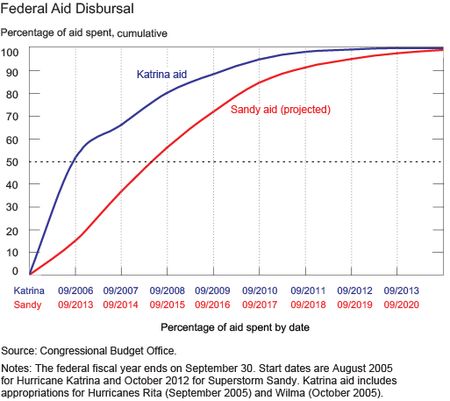

Moreover, the timing of the stimulus spending will be spread out. The chart below shows the projected payout of federal aid for Sandy relief, and compares the current time frame with the payout time frame of federal aid following Hurricane Katrina. With Katrina, half of the federal dollars were spent within the first year of the storm. With Sandy, projections suggest it will take nearly three years for the first half of the federal dollars to be spent in the region. Assuming private insurance payments are made within the first two years of the storm, this pattern implies that the outside stimulus will represent around 1 to 2 percent of annual GDP for the metro region over the next few years.

Could the Regional Economy Really Be Better Off?

It’s tempting to think that because of the amount of funds the region is receiving, economic prospects may actually be better now than they were right before the storm. However, the question of whether the economy is actually better off because of the boost to activity is a tricky one. Certainly, some stimulus occurs as spending is pulled forward that might normally have occurred later, perhaps over the next few years. For example, a family living in Far Rockaway, Queens, whose kitchen was destroyed will need to immediately replace items that might have otherwise lasted for another ten years, like a refrigerator. This replacement spending will provide a short-term stimulus, but this is primarily just pulling spending activity forward that would have occurred later anyway.

However, it’s important not to fall prey to what economists call the “broken window fallacy.” It argues that the activity associated with fixing a broken window—or replacing a refrigerator—does little to raise economic well-being and, at best, simply brings the window, and the economy, back to where it was before the window was broken—even if this money comes from an outside source. Much of the economic activity generated by Sandy will be used to restore what was lost from the storm’s damage. As we discuss in a previous post, the region’s economic costs from the storm are substantial, difficult to measure, and need to be weighed against any benefits of an increase in activity. So while economic activity may have been boosted from such spending, the region’s net wealth hasn’t changed.

The Potential for Productivity Gains

Of course, some of the spending that will occur is for more than just replacing things like broken windows. In fact, even when a new window replaces an old one, it’s likely to be one that’s better—for example, one that’s more energy-efficient. Thus, in the case of replacing things damaged from the storm, there’s some potential for improvements to the region’s productivity. Along these lines, much of the spending will be used to rebuild and upgrade the region’s critical public infrastructure, making it more productive. For example, Sandy destroyed sizable electrical and signal infrastructure of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) that was old and in need of repair. Given the MTA’s budget constraints, it’s not clear whether the agency would have upgraded the electrical and signal equipment without the $3.8 billion in Sandy relief funds. Notably, studies indicate that such investments in public infrastructure can increase the attractiveness of an area and raise its productivity for many years. So any investments that upgrade and reduce the risk to the region’s critical public infrastructure could provide a form of longer-term economic stimulus. While these longer-term benefits of disaster aid are easy to conceive, they’re hard to measure.

The Bottom Line

The region can expect to receive a small boost to economic activity as it continues to receive outside funds to rebuild after Superstorm Sandy. But the regional economy is only better off if this spending boosts the level of economic activity beyond what it would have been had the storm never occurred. This could happen if recent patterns of disaster relief persist—that is, if federal government funding and private insurance exceed the cost of the damage. In addition, there does appear to be a component of this spending that may provide a sustained increase in the region’s productivity by upgrading its critical infrastructure and strengthening its resilience to future storms of this nature. Still, it’s also important to remember that a large amount of the spending that will occur is simply restoring preexisting infrastructure.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jaison R. Abel is a senior economist in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jaison R. Abel is a senior economist in the New York Fed’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jason Bram is a senior economist in the Group.

Jason Bram is a senior economist in the Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Group.

James A. Orr is a vice president in the Group.

James A. Orr is a vice president in the Group.

Kaivan K. Sattar is a senior research analyst in the Group.

Kaivan K. Sattar is a senior research analyst in the Group.

Eric Stern is a senior policy analyst in the Communications Group.

Eric Stern is a senior policy analyst in the Communications Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics